Connections With Strangers: A Photo Series Offers a Window Onto the World

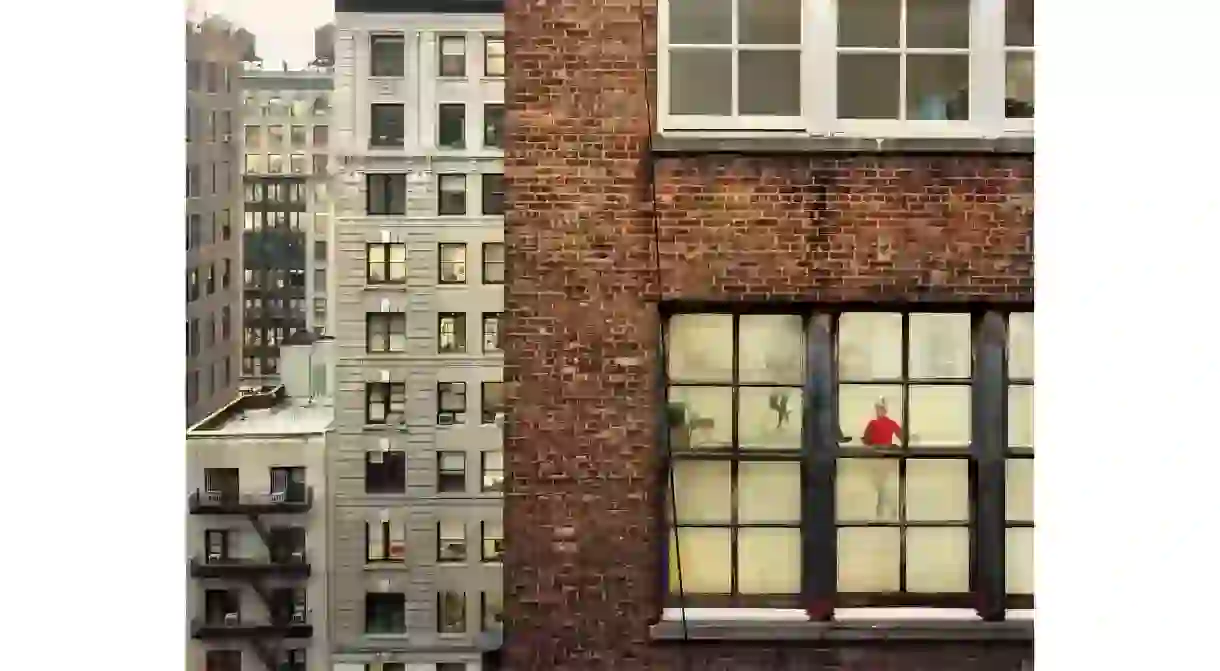

Gail Albert Halaban’s global art project explores the bonds we make with our neighbours by watching them in their homes.

This story appears in the third edition of Culture Trip magazine: the Gender and Identity issue.

When Gail Albert Halaban’s daughter turned one, she received balloons, flowers and a note from some neighbours she had never met. The note read, “We’ve had fun watching your daughter grow up, have a happy birthday.” At first, Halaban, an artist and photographer, was a little creeped out. “But then we met them to say thank you and I realised it was such a warm, sweet gesture and we connected so much through the window, I was curious to see who else had this relationship,” she says.

She began asking everyone she met if they watched their neighbours. (Almost everyone did.) “And I said, ‘Let’s go meet them! Let’s leave a note!’” Those who were willing (only one person has ever said no) became part of a collaborative photographic portrait, captured through their apartment window, looking at the ‘stranger’ across the way.

The scene is staged – Halaban is in constant conversation with the subject – and deliberately lit to make it clear that they know she is photographing them. She doesn’t shoot with a telephoto lens, instead wishing to see the scene – always quotidian actions like making coffee – from the perspective of the watcher. The resulting pictures are Hopper-esque, revealing at once the isolation and humanity of connecting with someone unknown.

When Halaban began the project, she had just moved to New York from a Los Angeles suburb where neighbours converged on front lawns. “This was a way for me to engage with my new neighbourhood,” she says. It wasn’t until she went to all five New York boroughs that she realised: “This tells me something about this city which is unique.” The Out My Window series has since expanded to every continent, shedding light on how people interact in ways specific to their culture.

All the New Yorkers she met were willing to participate. “This belief that it’s OK to meet your neighbour and broach this window gap is a very New York idea,” she says. In Istanbul, everyone was happy to participate but would not be the one to go and meet their neighbour. Parisians initially said “there is no way this is legal”, but once Le Monde got involved and advertised the project on bus shelters, it “became very chic to be part of it”. In Italy, people were thrilled for an excuse to see who was really living across from them. “They all had these long stories about who the neighbours might be,” Halaban says.

Halaban has been photographing in this way for 14 years. When she started, there was no Instagram, and Facebook had only just been launched; images were disseminated in a far more controlled way. “As this project has evolved, photography in our life has evolved. We don’t have any control over it. So I want to turn that concept around and make a photograph a very deliberate process and the opposite of surveillance.” She also believes these connections through the glass give comfort to people living in an otherwise faceless metropolis. “Looking through our window at these neighbours and creating these imagined stories creates community and empathy in a way that I don’t think we have when we get to know people online.”

This story appears in the third edition of Culture Trip magazine: the Gender and Identity issue. It will launch on 4 July with distribution at Tube and train stations in London; it will also be made available in airports, hotels, cafés and cultural hubs in London and other major UK cities.