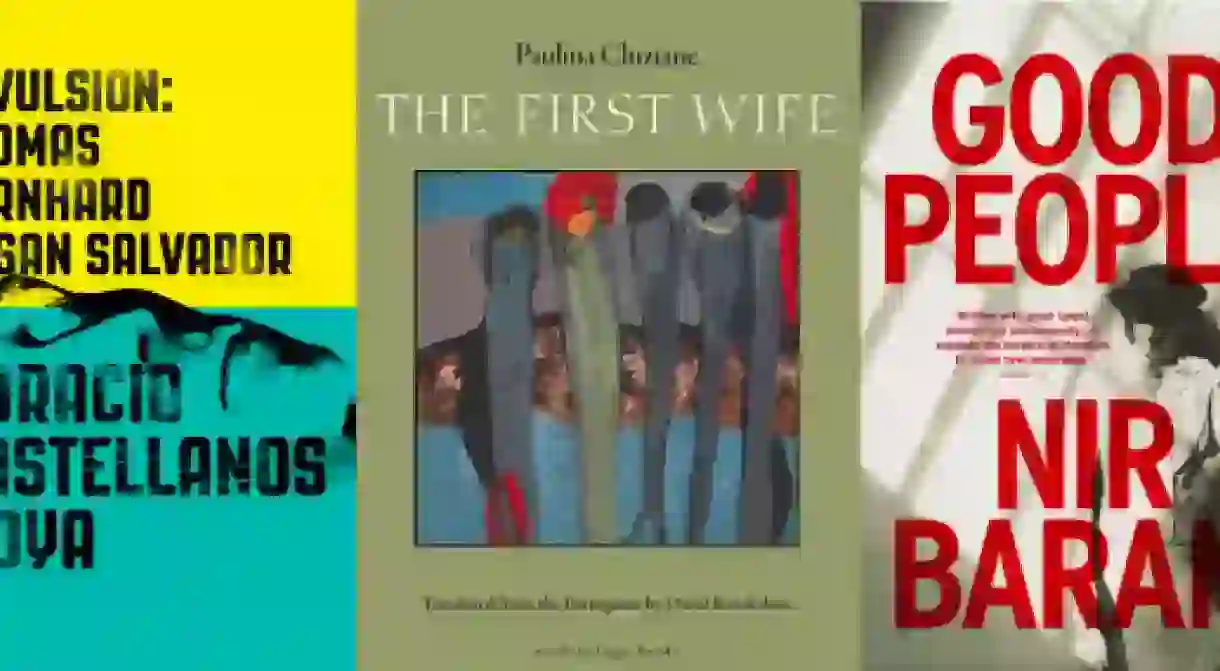

International Lit in Brief: New Books from Mozambique, El Salvador, and Israel

In a new installment of brief reviews, we take a look at three new books from across the globe.

_______________________________________________________________________

Paulina Chiziane, The First Wife, (Archipelago Books)

Translated from the Portuguese by David Brookshaw

Polygamy is widely condemned and, throughout much of Africa and Oceania, widely practiced. In Mozambique, where Paulina Chiziane’s novel The First Wife is set, the only deterrent against a man finding multiple wives is his inability to legally marry them all under state law. The practice itself is not considered a crime. Polygamy is allowed under the country’s customary laws, and only the first wife is protected by the state’s marriage laws. It’s these head-spinning loopholes that rope around the neck of Chiziane’s protagonist Rami, the first wife of a philandering police officer. When Rami discovers that her husband Tony has been fathering children with four other women, she weeps and then in a pique of desperation has a magic charm tattooed “in a secret place.” Then she seeks out the others, not in anger, but to coerce them to band together and force Tony to marry them all. To further twist his arm, they have him sign a contractual agreement that is typed up and stamped on official paper. From there the book turns into a family drama of unexpected proportions. At a dinner with all of the wives, Tony runs down the list of the virtues of each: “Maua’s my little bantam…Saly’s a good cook…What of Rami? She’s my queen, my pillar…” The dinner is a trap: Tony has found yet another woman, a light-skinned lady named Eve. “You’re all dark, a bunch of black women.” But Tony’s tail-chasing eventually gets the better of him and the woman start noticing other men, including Rami. But The First Wife, smoothly translated by David Brookshaw, rises above its satire by confronting a mysogynistic practice head on. In one scene, as Rami tries to comprehend her husband’s infidelity, she vox pops her neighbors, men and women:

I asked women: What do you think of polygamy. They reacted like gasoline set off by a spark. Explosions, flames, tears, wounds, scars. Polygamy is a cross to bear. A burning brazier … I asked men: What do you think of polygamy…I saw smiles stretching their lips from ear to ear…they applauded. Polygamy is nature, destiny, our culture, they said. There are ten women for every man in this country…polygamy is necessary, there are lots of women.

Chiziane, who prefers to be called a storyteller instead of a writer, is cited as her country’s first published female novelist. It’s no surprise that she would take up issues that keep women underfoot, with The First Wife being an excellent example of her courage.

***

Horacio Castellanos Moya, Revulsion: Thomas Bernhard in San Salvador (New Directions)

Translated from the Spanish by Lee Klein

“My country you do not exist” wrote Salvadoran poet Roque Dalton, “you’re my silhouette badly drawn.” Roque is referencing El Salvador, and could easily epigraph contemporary Salvadoran writer Horacio Castellano Moya’s novel Revulsion: Thomas Bernhard in San Salvador. The spirit, or rather spit, of Bernhard drives Moya’s propulsive fictional barroom rant to a fire-and-brimstone philippic. Moya plays himself in the book as the ear that listens to the drunken rant of Edgardo Vega, a Salvadoran who has returned to San Salvador for his mother’s funeral. The two are sitting in a bar, where Eduardo cashiers his country from the national university: ‘disgraceful… like a refugee camp’ to its national dish ‘only hunger and congenital stupidity can explain why human beings here eat something as repugnant as pupusas.” Revulsion may sound like an onslaught of vitriol and it is, yet its an effective tactic to what leads up to become a brutal criticism of the country’s leaders, rebels, and ruffians:

Thugs in this country kill without a motive, for the pure pleasure of the crime, they kill even if you don’t resist, even if you give them all they ask for, every day they kill without any other reason than the pleasure of killing… What taste the people of this country have for living in fear.

Only a few lines later finds Vega leering about the poor quality of the city’s brothels. In Moya’s acerbic tirade, which burns brightly through translator Lee Klein, the comedy is often as dark as the bruises.

Revulsion has become infamous. Roberto Bolaño called it, “the kind of book that makes you laugh out loud.” Other people didn’t find it so funny. In his author’s note, Moya recalls having his life threatened upon Revulsion’s publication: ‘I wanted to demolish the culture and politics of San Salvador,’ writes Moya, ‘same as Bernhard had done with Salzburg, with the pleasure of diatribe and mimicry. I didn’t foresee that reactions, including those of some loved ones, would be so virulent: the wife of a writer friend threw her copy into the street, out of her bathroom window, indignant, thanks to Edgardo Vega’s barbaric talk of pupusas, the national dish of El Salvador.’ Moya, who has lived abroad since the book’s publication, most notably in the United States, has had several works published in English, mostly by the independent press New Directions. Despite a growing reputation in the English-speaking world, Moya notes that his standing is less assured back home: “like a stigma, this imitation novel and its aftermath pursue me.” Dalton, as he points out, was killed by the very revolutionaries that once hailed him.

***

Nir Baram, Good People (Text Publishing)

Translated from the Hebrew by Jeffrey Green

When Good People was first in Israel published in 2010, Nir Baram was invited to give a talk at the International Writers Festival of Israel. “Kafka said that a book should serve as the ax for the frozen sea within us,” he said as quoted by the New York Times. He went on to decry the abuses of rights toward non-Jews in Israel. This is Baram’s wheelhouse: to use literature to cut through the frozen relations of historical enemies, not so much to have them thaw as to have them bob as icebergs in the same waters. As a title, Good People serves as both ruse and remedy: its two main characters—Thomas Heiselberg, a German businessman, and Alexandra “Sasha” Weissberg, a Soviet intelligence agent—are caught in that fireball European era leading up to the Second World War. Heiselberg has managed to work his way up to executive level for the Berlin branch of an American market research company (sort of a fictional Nielsen). His mother’s Jewish maid has been forced to quit and a friend Hermann has eagerly joined the SS—one scene depicting the horrific Krystalnacht ends with Hermann chiding: “Run along now, Thomas. On a night like this, you really shouldn’t leave your mother all alone.” But Thomas is fated to leave Berlin—a rival sees to that—and he ends up in Brest, Poland (now in modern-day Belarus).

Far away in Moscow, Sasha witnesses her family being plucked away by the NKVD: her father and mother are shipped to the gulag; her twin brothers to an orphanage. Sasha is given a devil’s deal and spared extraction by working for the very organization that has laid its claws on her life. When she comes to a head with her NKVD superiors, she too is shipped off to Brest. Baram didn’t pick the former Polish city to conclude his novel by accident: it was here, on September 22, 1939, three weeks after Germany invaded Poland, that during a brief truce, the German and Soviet armies held a joint parade. But here Baram twists history: it is 1941 and Sasha and Thomas are tasked with organizing a new, more ceremonial peace parade. Their unlikely relationship develops at an improbable pace—their first planning session turns into a pseudo-date—as though Baram is in hurry to shoehorn an intimacy into the catastrophic events to come. It’s disorienting, but hardly a stumble: Good People grander vision brings to mind the Inferno with Baram as our Virgil.

Baram’s Good People has been showered with praise for its elegance prose and scope. It highlights the kinds of people that not only suffered, but thrived under the aegis of the Nazis and Red Army. In one scene, Sasha has been called into her boss’s office, and in one gesture—a scowl—she sees him for an oaf: “The man who had sent tens of thousands of people to prison, Siberia and death, was actually an absent-minded creature, slightly built and bespectacled, playing a role too big for him. In his defense he knew it.” By putting the types of people who brought about the Second World War under a microscope, Baram creates an allegorical warning bell. Perhaps Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung put it most succinctly in its review of the German edition: “Quite possibly, Dostoyevsky would write like this if he lived in Israel today.” If Baram wrote this well at 34, we will all do well to await his next book World Shadow, which takes aim at the corruption of the Israeli Left.

by

Paulina Chiziane / Horacio Castellanos Moya / Nir Baram

494 pp., $18.00 / 128 pp., 13.95 / 432 pp., $15.95