Art as Protest: The Historical Context of Significant African-American Artworks

As unrest escalates in the United States with nationwide protests for murdered African-American George Floyd, Culture Trip stands with the Black Lives Matter movement. In solidarity and in celebration of African-American protest art, we look at some of the most significant artworks from the past 100 years that confront systemic oppression.

In 1967, the year before mass social unrest and before the four days of upheaval that would follow his assassination, civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about riots. He called them “socially destructive and self-defeating,” but, he argued, “in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard.”

This week across the United States, we have seen protests erupt. James Fallows for The Atlantic likened the turmoil of the King assassination riots in 1968 to those of late, and questioned whether 2020 could be the worst year in modern American history since. But these riots haven’t come from nowhere. They follow the murder of George Floyd, an African-American man from Minneapolis, at the hands of police brutality. His untimely death, which has been compared to lynchings of the 19th century and triggers déjà vu of Eric Garner’s murder six years ago, is the tip of the iceberg of centuries of systemic oppression. The final utterances of both of these men – “I can’t breathe” – has become a metaphor for this long history of injustice.

As tensions rise to the surface, it’s important that collectively we educate ourselves and stand up for what is right. Racism is not tolerated. Peaceful protests are widely encouraged – and being practiced across the USA with the UK in solidarity. Meanwhile, something that speaks to us all on a visceral level is art. And so, as we stand together with Black Lives Matter, Culture Trip curates and explains some of the most significant artworks in modern history, created by African-Americans, that endure as expressions of protest.

Augusta Savage, ‘Realization’ (1939)

1920, Harlem. An explosion of African-American art, music and literature rises through the city. It comes to represent the start of the golden age of African-American culture known as the Harlem Renaissance. Sculptor and civil rights activist Augusta Savage is at the centre of this, along with her contemporaries like poet Zora Neale Hurston and visual artist Aaron Douglas, all of whom campaign for equal rights for African-Americans through their craft.

In 1939, as Savage became the first African-American woman to set up her own gallery, she asked that her work and that of other black Harlem artists be judged only on its merit. “We do not ask any special favours as artists because of our race,” she said. One of the works in this exhibition is Savage’s sculpture, Realization, (1939); cast in plaster and painted with shoe polish to mimic bronze, it shows a black couple collapsed into one another; vulnerable, exposed. It has since been interpreted as a commentary on slavery and oppression. “It’s about the psychological trauma of the moment after this couple has been sold, stripped to go on the auction block,” curator Wendy NE Ikemoto told The Guardian.

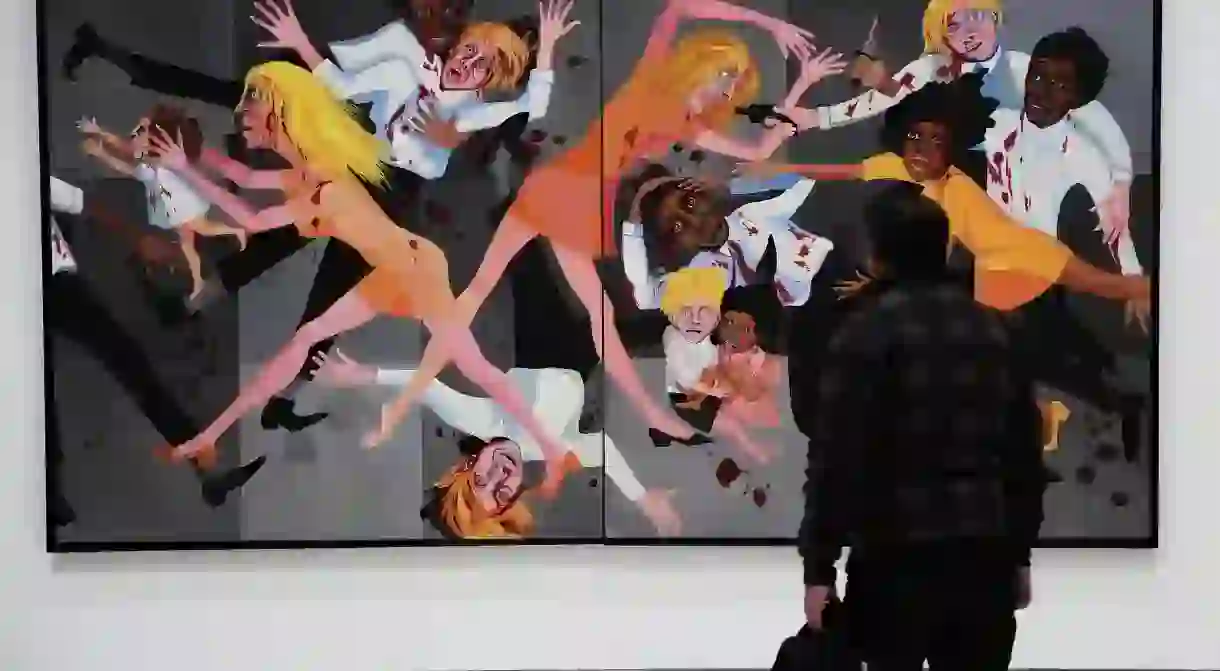

Faith Ringgold, ‘American People Series #20: Die’ (1967)

The 1960s saw race riots break out en masse in America. In the years before the four-day-long 1968 King assassination riots, in which over 40 people died, looting and arson ripped through cities including New York, Detroit, Washington DC, Chicago and Newark over a period of time where over 150 riots were recorded. In July of 1964, six-day-long riots broke out in Harlem following the murder of a 15-year-old African-American, James Powell, at the hands of a white off-duty police officer. The anger spread around the country, and rioting followed around the country – cities including Rochester, Jersey City and Dixmoor, Illinois saw race riots for the first time.

Meanwhile, in August of 1965, “the largest and costliest urban rebellion of the civil rights era” took place in Los Angeles. The Watts Riots lasted for six days and left 34 dead after an African-American man was pulled over by a white policeman. Artist Faith Ringgold sought to capture the upheaval in her 1967 artwork, American People Series #20: Die. “In 1967 alone – the year Ringgold painted this work – 83 people were killed, 1,800 injured, and property valued at more than $100 million was damaged, looted or destroyed,” The Washington Post wrote. Her painting captures both black and white individuals in equal distress to illustrate that everybody was involved in this unrest. “Ringgold wanted people to understand that the riots were ‘not just poor people breaking into stores’. They were about white flight, urban blight, dying industries. They were about, she said, people trying to maintain their position, and people trying to get away,” The Washington Post reported.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, ‘Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart)’ (1983)

Crime was at an all-time high in New York back in mid-1970s to 1980s. “The number of murders in the city had more than doubled over the past decade, from 681 in 1965 to 1,690 in 1975. Car thefts and assaults had also more than doubled in the same period; rapes and burglaries had more than tripled, while robberies had gone up an astonishing ten-fold,” The Guardian reported. A 1975 welcome guide to “Fear City” circulated, advising visitors to stay off the streets after 6pm – and wished them luck. This was the environment surrounding Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was an up-and-coming black artist at the time, graffiting the city under his SAMO alias. State violence – the kind that still perseveres – was real, too. And no more real for Basquiat than in the case of artist Michael Stewart. In 1983, the graffiti artist was caught in the act at the First Avenue Subway station and beaten to the point of brain damage, dying 13 days later. The officers were acquitted. The pain and anguish Basquiat felt carried through to one of his most powerful works, Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart); the artist recognised it could have been him – or anyone else in the black community. It was important that he contribute to the conversation about state violence on his community. About the artwork, art historian Chaedria LaBouvier told The Guardian: “It’s not qualifying, it’s not showing this noble aspect of someone’s humanity. It’s just what he felt. It’s just the rawness of what happened.”

Thornton Dial, ‘Top of the Line’ (1992)

Thornton Dial was an artist known for experimentation and expression – working with found materials was a theme in his large-scale artworks of the 1980s and 1990s. When 1992 came around, the artist turned his attention to the uprising in Los Angeles that followed a jury acquitting four white policemen who had beaten unarmed construction worker Rodney King to a pulp. The riots saw over 12,000 arrested and 63 people dead, with widespread looting and arson. Thornton captured this frenzy on canvas in his work Top of the Line, which according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum has a double meaning: “[It is] referring to the quality of the stolen merchandise and the socioeconomic struggle for equality,” it wrote. Outlined by rope, his work features black-and-white figures representing racial tensions, while spats of white, blue and red nod to patriotism, with the latter also suggesting violence. On his artistic output, the artist famously said: “I make art that ain’t speaking against nobody or for nobody either. Sometimes it be about what is wrong in life.”

Kara Walker, ‘The Daily Constitution 1878’ (2011)

Contemporary artist Kara Walker has been called “one of most complex and prolific American artists of her generation” for her works that explore race relations, identity and stereotypes in America. Never has this artist been afraid to go into dark places and bring to our conscience the legacy of racism, exposing the truths of what the black population has endured. “Her art engages with what many would rather forget,” wrote Laura Barnett for The Guardian.

One work that does so is The Daily Constitution 1878, which sees a lynched woman before her laughing assailants. Like most of what Kara visualises, the work looked to what actually happened in the past; the work is an interpretation of an 1878 clipping from the Daily Constitution that detailed the last moments of a black woman. “The mob had tugged down the branch of a blackjack tree, tied the woman’s neck to it, and then released the branch, flinging her body high into the air,” Barnett explained. For Kara, this artwork required such “perverse ingenuity” for the absurdity and violence of the situation. Of late, the artist has looked to past and racist reality of the present with Barack Obama as her subject. “An African” With a Fat Pig, is one compelling drawing, in which the former American president is captured “as a tribesman through the eyes of a colonialist”, as Artnet News reported. Her racially charged work continues.