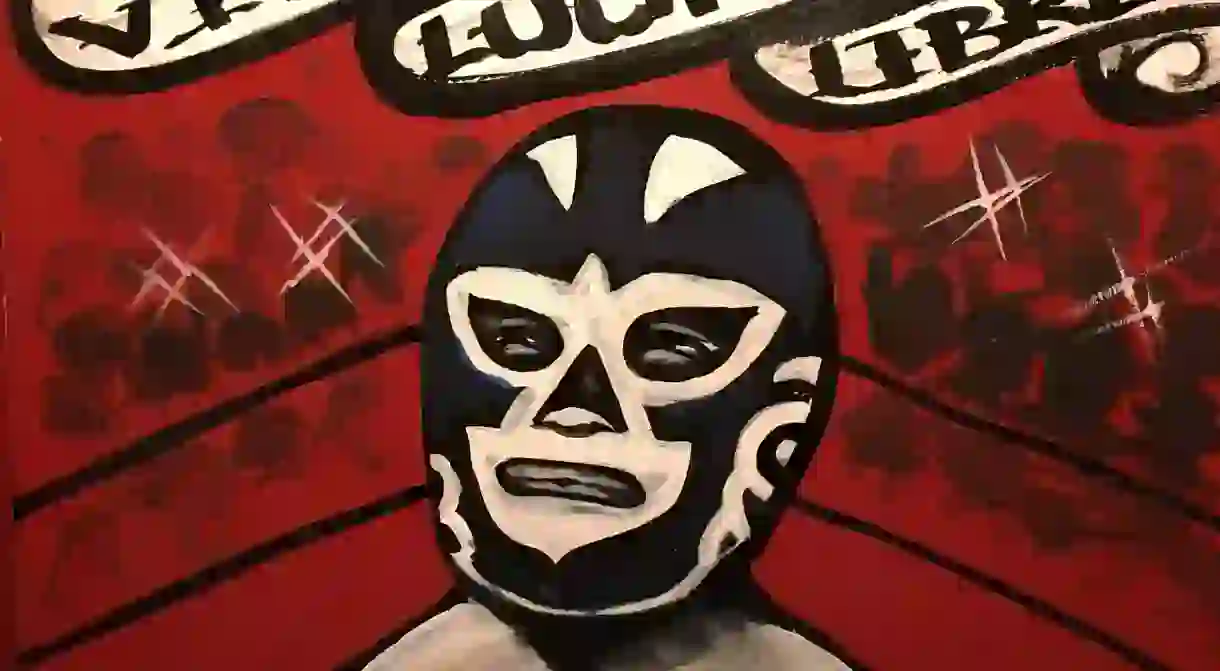

The Lucha Libre: A Brief History Of Mexican Wrestling

Mexican wrestling, or lucha libre, has a rich history that dates back over a century and is characterised for its over-the-top performances, Lycra-clad luchadores and macho-man atmosphere. Here’s everything you need to know about this particularly Mexican form of entertainment.

Mexican wrestling, in the form we more or less see it today, found popularity as a ‘sport’/ art form in the early 1900s; however, the origins of the lucha libre proper, date back to 1863. This was when Enrique Ugartechea developed a spin-off free-style wrestling format that differed from Greco-Roman tradition. It was the influence of Italian businessmen that brought it to the big stage though; in 1933, the so-called father of lucha libre, Salvador Lutteroth González, set up the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (nowadays known as the Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre, or the World Wrestling Council) and began promoting fights up and down the country. Due to the Texas origins of Salvador Lutteroth González’ inspiration, many early fighters were brought from the US, but gradually the Mexican luchador began to establish himself on the wrestling scene. Fighters have long been the main draw of the luchas, but a recent investigation found that they can only expect to make around MXN$25,000 per fight if they’re one of the top ranked performers.

The history of the infamous lucha libre masks supposedly dates back to 1933, when a wrestler by the name of El Ciclón McKey commissioned Don Antonio Martinez to make him a mask for his upcoming fight. The mask proved wildly successful, almost impossible to pull off mid-fight, and left an indelible mark on the history of the lucha libre, as well as spawning a wave of copycat enmascarados (masked ones). Don Martinez’ original store is still in existence to this day and can be found near Mexico City’s Arena Mexico.

The real love for the lucha libre in mainstream Mexican culture didn’t come until the Golden Age of Lucha Libre in the 50s and 60s though, and was probably spurred on by the huge popularity of El Santo, one of Mexican wrestling’s most legendary and beloved names. Never de-masked throughout the duration of his career – which began in 1942 – he revealed his true identity to the public shortly before his death in 1984 and was subsequently interred wearing his trademark silver mask. He, along with the advent of television, helped launch the lucha libre into the home of the common man as fights started to be broadcast nationwide. As love for the lucha libre waned slightly over the years, companies began to take tips from WWE and introduce special events such as King of King fights and mini-All Star specials, as well as female luchadora battles.

Historically speaking, other luchadores that have had as much of an impact on the art as El Santo include Blue Demon, Mil Máscaras (one of the first wrestlers to cross over into the US wrestling spectacles) and Huracán Ramírez (who put his own twist on the classic rana move, calling it the huracán rana).

Similarly, many wrestlers have a family history in the industry, inheriting both the mask and title of their forebear before stepping into the ring themselves. El Hijo del Santo is the son of El Santo, and Rey Mysterio Jr. is the great-nephew of Rey Mysterio, whereas Hijo de Rey Mysterio is his son. A strange twist to this familial tale though is that Villano IV is the fifth son of Ray Mendoza, whereas Villano V is rather confusingly the fourth!

It seems that the lucha libre looks set to live on for a while at least, as it has become popular with tourists wanting to see a ‘real’ side to Mexican culture and is even considered the second most popular spectator sport after football in the country. Even so, it’s not without its controversy. Popular luchador Eddie Guerrero died in 2005 due to suspected side effects of steroid abuse, El Pirata Morgan lost an eye in a lucha libre fight of the early days and, more recently, Hijo del Perro Aguayo died mid-fight in Baja California.