If You Love Dance, "Polina" Is the Movie for You

Juliette Binoche and ballet stars Anastasia Shevtsova and Jérémie Bélingard shine in a French film about dance as the meaning of life.

Early on in Polina, Danser Sa Vie, eight-year-old Russian ballet student Polina (Veronika Zhovnytska) heads home from her class. The sun is going down, huge nuclear cooling towers loom behind her. She breaks into a running dance, her petite form undulating joyfully, forwards and backwards, from side to side, to 79D’s propulsive industrial electronica. She suggests an automaton that’s metamorphosed into a wasteland sprite.

Like confetti

On touching the ground, Polina flicks snow into the air like confetti. Not until the end of the film does she again dance with such grace and freedom. By then, a decade or so has passed, and Polina (exquisitely played as a young woman by Mariinsky Theater dancer Anastasia Shevtsova) has suffered creative disillusion, romantic disappointment, and near destitution. The dancer in her could not be extinguished, however.

Watching Polina revive toward the end, dance fans might be reminded of the famous exchange in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948). Lermontov: “Why do you want to dance?” Victoria Page: “Why do you want to live?” The young Polina and her the taciturn middle-aged mentor Bojinski (Aleksey Guskov) had had a similar exchange. Bojinski: “What is ‘dancing’ for you?” Polina: “It happens by itself.”

Just as passionate

Co-directed by filmmaker Valérie Müller and dancer-choreographer Angelin Preljocaj, a French wife-husband team, Polina was adapted by Müller from Bastien Vivès’s graphic novel. It isn’t comparable to The Red Shoes, but—notwithstanding its awkward third act—it’s a dance film as passionate as Herbert Ross’s The Turning Point (1977) and Sandra Goldbacher’s Ballet Shoes (2007), while being more immediate than Robert Altman’s The Company (2003).

Polina’s journey of self-discovery is contextualized by male authority and whim, though her susceptibility to romantic love plays its ruinous part. She is the only daughter of working-class parents, Anton (Miglen Mirtchev) and Natalia (Kseniya Kutepova), who dream of her becoming a prima ballerina. They have enrolled her in a ballet school ruled with a rod of iron by Bojinski, whose progressive choreography had fallen foul of the Soviet establishment.

The Bolshoi abandoned

Anton is so intent on Polina being chosen for the Bolshoi that to pay for her classes he has gotten into debt with a loan shark. When this gorilla threatens the family with guns, Anton agrees to “drive the Afghanistan route”—shorthand for importing heroin. Imagine his anguish when Polina aces her Bolshoi audition (a neat offscreen elision) but runs off to join a modern company in Aix-en-Provence with her French dancer boyfriend Adrien—a lazy faun played by Niels Schneider.

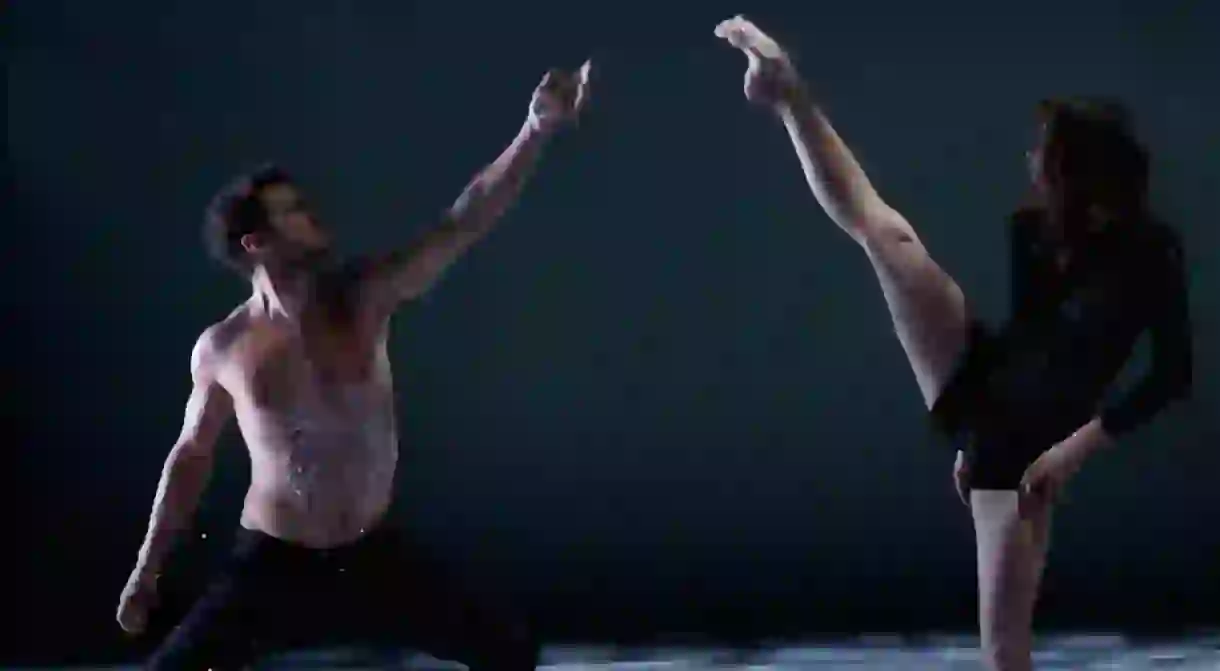

The Provençal company is run by Liria Elsaj (Juliette Binoche), whose choreography is more sensual and grounded than Bojinski’s, and based on the precepts of “danger,” “urgency,” “fear,” and intense longing for an absent lover.

Of Polina’s teachers, it is the earthy Liria rather than the perfectionist Bojinski who comes across as inflexible. She recognizes Polina’s talent and casts her as the lead in Snow White. Nonetheless, Liria frowns on Polina’s classical training and tells her to dance from a low center of gravity, which is counter to her training with Bojinski.

Dancing by herself

Liria further implies that Polina’s dancing is solipsistic, but when Polina spies on Liria smiling to herself when she dances alone, it is the older woman who seems self-satisfied. However, Polina does pick up the interdependent spirit of dancing pas de deux from Liria.

Later on, a third dance-maker—a man with the face of a fallen angel, whom Polina meets fleetingly—says he’s more interested in her observations than her dancing. She eventually starts watching people’s interactions on the street and in the subway and drawing on their evident emotions in her fledgling attempts at choreography.

Following an injury caused by Adrien, Polina loses the Snow White part. A more grievous insult by him causes her to quit Liria’s company and take off for Antwerp. She runs out of money and can’t afford lodging. Just when it seems she might have to prostitute herself, she gets an exhausting job tending bar in a rowdy, all-night club.

Fairytale ending

A chance meeting with a supportive and far too handsome male choreographer—played by Jérémie Bélingard, danseur étoile of the Paris Opera Ballet—spins the movie toward a fairytale ending, though not before Polina takes another emotional blow. The film’s final dance sees Polina happily using the free-spirited swerves she exhibited on the wasteland all those years before.

Though elegantly filmed by Müller and Preljocaj, Polina features a number of poor choices late on: a quick cutaway to Bojinski moping in his studio (presumably because Polina didn’t fulfil her promise with the Bolshoi); shots of Polina and Bojinski looking directly into the camera, as if at each other in a spiritual rapprochement. An encounter in which they are unable to say anything to each other would have spoken volumes more.

Still, as a movie about finding your feet—in holding on to your essential self and relocating your mislaid artistic integrity—Polina is ultimately en pointe.

Polina opens in theaters this Friday.