Actress Stacy Martin: "We Didn't Want to Crucify Jean-Luc Godard"

The Anglo-French actress enthuses about playing Anne Wiazemsky, Jean-Luc Godard’s second wife and muse, in Michel Hazanavicius’ Godard Mon Amour.

Based on Wiazemsky’s novel-cum-memoir Un an Après, Godard Mon Amour traces the effect that participating in the May 1968 protests in Paris had on the morale, career, and marriage of the erstwhile New Wave master.

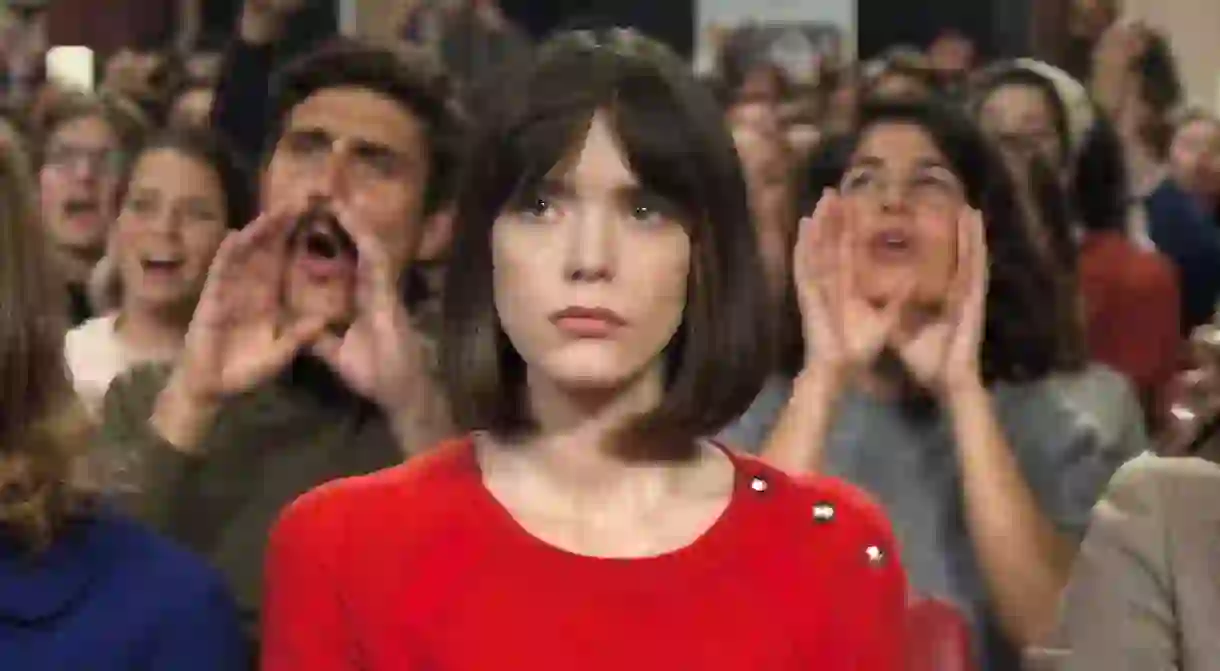

The Artist (2011) director Hazanavicius’ latest film has received mixed reviews, but no one can fault the performance of the 27-year-old Martin who is as thoughtful and restrained as Louis Garrel is droll and provocative as Godard—until he has to relay the director’s growing self-absorption and depression. Martin’s Wiazemsky is the even keel here.

Previously best known for her creation of callow, lusty young Jo in Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac (2013), Martin talked penetratingly about Wiazemsky and Godard when she met with Culture Trip recently in midtown Manhattan.

Culture Trip (CT): Did you meet Anne Wiazemsky?

Stacy Martin (SM): I’d made the decision not to meet her when I was preparing for the film, and I was nervous about meeting her at the premiere at Cannes last year because I wanted her to enjoy the film and see that I had portrayed her in my own way, without doing a “copy-paste” performance.

At the premiere, I was wearing a dress with a train, which I’m not used to, and someone stepped on it. I’m very English so I said, “Oh, I’m sorry—it’s my fault.” And a voice said, “No, I’m sorry—I’m the one stepping on your dress.” And it turned out to be Anne! We just looked at each other. I didn’t know what to say to her, but there was a quiet understanding between us and we went to the screening and held hands and celebrated the moment. It was beautiful.

CT: Did she say anything to you afterwards?

SM: She said thank you and that she was really proud of the film. She thought it was great that Michel had managed to make a comedy out of something tragic. That’s what comedy is really, you turn something extremely upsetting into something funny.

CT: Godard Mon Amour humanizes Godard through the love story.

SM: You forget the mythical figure who has revolutionized cinema and you see Jean-Luc, an artist going through a very natural process of questioning his work and where he’s come to. He was probably having a midlife crisis at the time of the May ’68 revolution. We didn’t want to make the film a biopic or a caricature of him—we wanted to make it the story of these two people who are at opposite moments in their lives.

CT: Did you know much about Godard beforehand?

SM: Growing up in France, you live and breathe Godard, even though you don’t know you do. I knew his early work best—Breathless [1960], Une Femme Mariée [1964]. I saw Masculin Féminin [1966] in a cinema, and it blew me away because it’s breathtaking on the big screen. But before we did our film, Michel said, “Watch [François] Truffaut rather than Godard,” so I saw a lot of Truffaut’s films.

CT: In Godard Mon Amour, there’s a tracking shot alongside your body that recalls Godard filming the nude Brigitte Bardot in Contempt [1963].

SM: Godard objectified the women he filmed, but in the most beautiful way—their bodies become pieces of art. Sometimes, he almost makes collages of different body parts. Michel wanted to re-use that idea because he wanted to show how Anne changes from being this idealized woman in Godard’s films to being her own person. The love scenes and the nudity scenes were very volontaire, by which I mean we did them very consciously.

CT: Owing to Godard’s obsession with revolutionary change, he loses sight of this vital young woman he’d married. He says early on in the film, “I knew she would leave me,” so the relationship was foredoomed.

SM: The fact that his films had become commodified entities as part of the New Wave was unacceptable to him. When May ’68 happened, he couldn’t not revolutionize himself. If he was going to do something at that time, he was going to do it a thousand percent, and he couldn’t question his art or his place in life without questioning the other films he’d made or his relationships, including, obviously, his relationship with Anne. It’s tragic to see someone you love becoming someone else. You ask yourself, is it still real? Is it still there? Can it come back if it’s not? Anne was that much younger than Jean-Luc and she wanted to define herself, whereas he wanted to un-define himself.

CT: The film positions Godard as the politicized intellectual and Anne as an intelligent woman who wants to have fun. Do you think it does justice to her intellect?

SM: I think it does in the context of a love story. Before filming, we did a reading of the script with all the cast. I probably had 12 lines, and Louis [Garrel, who plays Godard] spoke the whole time. I thought, “Well, I don’t want to fall into the role of being secondary to someone who’s constantly talking, questioning, attacking, and negating things. How do you balance that?” I think Anne’s force is in observing the man who does all this, which doesn’t negate her value or her intelligence.

It isn’t a film about Godard, and it doesn’t show the parts where Anne and Jean-Luc met and exchanged letters and fell in love, their amazing conversations and walks. Michel chose to make a film about a specific stage in their life together, but it’s a moment in which Anne found she couldn’t define herself. It shows Jean-Luc taking up so much space that Anne has to leave him. There was no room for her in the relationship.

CT: The film and Louis Garrel’s performance make it possible to empathize with Godard.

SM: Yes, we didn’t want to crucify him.

CT: Anne had tremendous charisma and allure for directors. As well as Godard, Robert Bresson was obsessed with her, and she became close to Pier Paolo Pasolini, too.

SM: You see [her charisma] on screen in Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar [1966] and Godard’s La Chinoise [1967]. It’s not surprising she became Godard’s muse.

CT: You presumably haven’t met Godard?

SM: No, no, no. [laughs]

CT: He said Godard Mon Amour was “a stupid, stupid idea.”

SM: Even if he had been aboard, he would never have said he liked it. It’s part of his character to be anti- things. We don’t know if he’s seen it or not.

CT: Finally, I’ve got to ask you if you’ve recovered from making Nymphomaniac yet?

SM: Well, hopefully [laughs]. I loved that experience. The thing about Nymphomaniac, it’s a lot harder to watch than it was to make. It was a very obvious decision for me to make it; I didn’t really think twice about it. At the time I didn’t have an agent and I didn’t know anything about the film industry. That gave me the freedom of not having anxiety about it being right for me or not, and it turned out to be exciting. It gave me a chance to make acting my job.

Godard Mon Amour is screening at The Landmark at 57 West, 657 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019. Tel: (646) 233-1615.