The Tale of the First Ever Christmas Card and Its Fascinating Design Evolution

Ever wondered why we send Christmas cards, where the tradition originated from and who designed them in the first place? Home and Design Editor Charlotte Luxford spoke to Tim Travis, Curator of Word and Image at London’s Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, to ask how Christmas cards have evolved over time and the social and cultural factors that have influenced their designs over the years.

Culture Trip: How and why did the first Christmas card come about?

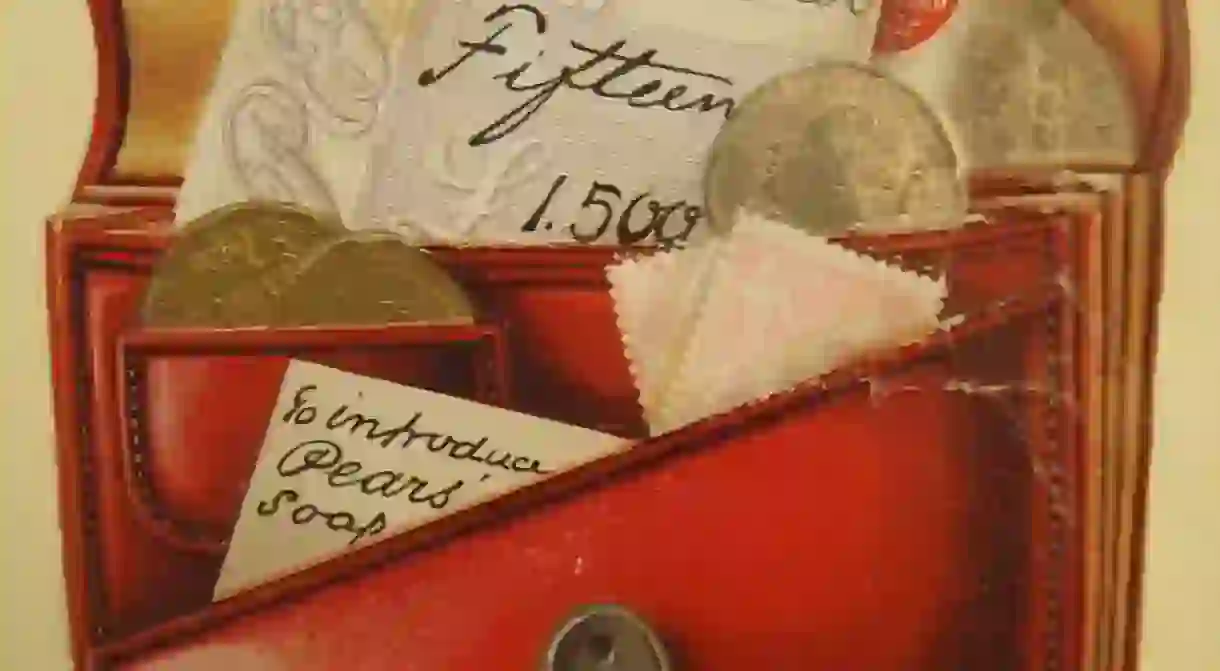

Tim Travis: In 1843 the civil servant, entrepreneur and future director of the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A Museum), Henry Cole, was too busy to send his usual Christmas letters to all his friends and acquaintances, so commissioned his friend, the artist John Callcott Horsley, to design a card for him to send instead. The design was reproduced lithographically in an edition of 1,000 by the printing firm of Jobbins of Warwick Court, Holborn, and hand-coloured by a professional ‘colourer’ called William Mason. The cards left over were then sold by Cole’s business partner, Joseph Cundall, at their emporium, Summerly’s Home Treasury, for the then-princely sum of one shilling each.

Summerly’s Home Treasury was one of Cole’s reforming enterprises established under his pseudonym of Felix Summerly to publish and sell well-designed and illustrated children’s books and games. On a single sheet of stiff pasteboard (about the size of a modern postcard), Horsley’s illustration depicts three generations of a Victorian family drinking a toast to the recipient over a banner with the greeting, ‘A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You’. The central image is flanked by side panels showing acts of Christian charity (feeding and clothing the poor) and framed by a trellis of branches overgrown with vines suggestive of seasonal abundance. The cards were not a commercial success – the price was considered too steep and the design was criticised because it was suggested that the central scene would encourage drunkenness – and they were eventually withdrawn from sale.

CT: How did the Christmas card evolve with the Christmas trend in the mid-to-late 19th century?

TT: Christmas cards didn’t become popular until the 1860s and later. Writing paper or visiting cards decorated with printed Christmas motifs or embellished with seasonal scraps were more popular substitutes for the traditional Christmas visit or letter through the 1840s and 50s. Advances in cheap colour printing and cheaper and more reliable postal services gradually made the sending of Christmas cards more attractive to the mass market.

CT: What type of themes or motifs featured on the early Christmas card designs?

TT: Early Christmas cards often featured flowers or springtime or summer scenes. There were two reasons for this: early Christmas card manufacturers had previously made Valentine’s cards, which preceded Christmas cards in popularity by several decades. There was no guarantee that Christmas cards would ever be as popular as Valentine’s and so instead of commissioning new illustrations and creating new printing plates they adapted existing ones and simply added a seasonal greeting. Also, sunny, flowery scenes cheered people up during the long, dark, cold winter months before the invention of electric lighting and central heating.

The seasonal Christmas themes familiar to us today came a little later – influenced by popular literature. Besides Charles Dickens‘ A Christmas Carol (1843), two other publications were very influential on the visual culture of Christmas in the mid-to-late 19th century: Christmas with the Poets by Henry Vizetelly, illustrated by Myles Birket Foster, published 1852 and The Old English Christmas by Washington Irving, republished in 1876 with illustrations by Randolph Caldecott. Both were extremely popular, widely read and reviewed, and frequently re-issued. Much of the familiar iconography of Christmas – robins, holly, mistletoe, eating and drinking, games and entertainment, Father Christmas, presents, etc – comes from these and similar popular books published in the 19th century.

Then as is now, religious cards were relatively uncommon, perhaps because Christmas cards were regarded as an extension of secular social customs like Christmas visits and letters, and had no precedent in religious observance. Where religious motifs did appear, they were often crosses and flowers or purely sentimental imagery with a devout greeting or scriptural quotation added rather than nativity scenes.

CT: Christmas cards were expensive to start with, so what changed?

TT: They were relatively expensive items by today’s standards. Henry Cole’s first Christmas card was laboriously hand-coloured and priced at a shilling each, which was about the daily wage of a working-class person. Regarded as a luxury, Christmas cards were initially marketed as tasteful ‘artistic’ products for the discerning. Later advances in colour printing technology enabled mass production and economies of scale which brought a flood of relatively cheap cards onto the market. They were often sold in packs with names like ‘The Penny Basket’ or ‘The Halfpenny Basket’ (a dozen or half a dozen cards for a penny or halfpenny). Often imported from Germany, they were illustrated with more popular less ‘aesthetic’ scenes and were rather unfavourably regarded by some reviewers at the time.

CT: Why were Christmas cards so popular during the Victorian heyday in particular?

TT: A variety of factors came together in what the late historian of Christmas cards Georges Buday called ‘the fullness of time’: improvements in postal services (the penny post went nationwide in 1840 and the halfpenny post for single-sheet postcards in 1870); new technologies allowing cheaper methods of mass producing printed goods (especially in colour) such as books, games and stationery; the establishment of trades and retail outlets to supply relatively non-essential novelties and luxuries to a growing middle class with disposable income and leisure time; greater social and geographic mobility, etc.

CT: Who were the prominent illustrators and publishers behind Christmas cards during this time?

TT: Some important card illustrators of the time include Robert Dudley, a prolific designer between the 1870s–1890s, who’s known for narrative illustrations of robins and neo-classical allegorical subjects; Kate Greenaway, a famous children’s illustrator during 1860s –c. 1900 who designed mainly for Marcus Ward & Co, which was a very important 19th-century Christmas card publisher. Louisa Beresford (Marchioness of Waterford) and Louis Wain both produced images mainly for the firm of Raphael Tuck & Sons – it was the longest-running producer of Christmas cards, and tried to cater for all tastes and incomes.

Probably one of the most important figures was Louis Prang, who was called ‘the father of the American Christmas card’. He emigrated to USA from Silesia in 1850, and was an idealist reformer and businessman. He was innovator of the ‘Prang method of education’ and set up as lithographer L. Prang & Co in Boston in c. 1860. He then perfected the process of printing in up to 32 colours using zinc plates instead of lithographic stones enabling economies of scale and quality of reproduction that revolutionised the market for mass-produced colour printing.

He began printing fine art reproductions but moved into Christmas cards after the introduction of the one-cent post in 1873, with the aim of bringing good taste to the masses. The firm offered superb quality colour reproduction of designs from leading artists and illustrators, producing five million cards a year at its peak – the company set the scene for 20th-century American domination of the industry.

CT: How has the British Christmas card evolved during the 20th century?

TT: After the 1860s–1890s heyday of the Victorian Christmas card, they declined somewhat in popularity (and quality). Until about the 1920s-30s, single-sheet cheap Christmas postcards were more popular. During the First World War, a ban was considered to conserve paper supplies but was eventually rejected for the sake of morale. In France and Belgium during 1914–18, a cottage industry flourished producing embroidered postcards for troops to send home to loved ones. It was also during this period that cards for particular relatives (‘to my dear mother’, ‘for my beloved wife’, etc) became popular as a whole generation of working and middle-class men were separated from their families and neighbourhoods for the first time.

After World War One, there was a British revival in wood engraving as a medium of illustration and a nostalgic taste for folk or rural themes. Artists like Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, John Greenwood and Joan Hassall designed for small independent publishing houses and galleries. Folder cards cheaply printed in one or two colours on paper were typical between the wars.

The post-World War Two period saw many prominent modern artists such as Bernard Brett, Barbara Jones, Esme Eve, Henry Moore and John Piper designing cards. The 1950s’ ‘new look’ in fashion and interiors influenced graphic design, including cards. Corporate and advertising Christmas cards (including for department stores and airlines) became more common in the 1950s. The 1960s and 70s explosion in youth culture and fashion was reflected in the ‘funky’ and psychedelic cards designed by artists such as Marion Wilson, Danuta Laskowska and Jan Pienkowski for Gordon Fraser, Gallery Five and Elgin Court. The 1980s and 90s were characterised by two opposing trends: corporate chic – this was the heyday of inventively designed and expensively produced corporate Christmas cards, and low-tech ‘alternative’ culture – cheaply produced cards promoting left-wing or ‘green’ politics, feminism, pacifism, etc. For the millennium celebrations, trends included typography, metallic finishes, plastic, holography and lots of white, silver and purple for some reason.

CT: Where do you think the Christmas card sits in the digital age?

TT: Most art forms and the social conditions that generate them have a beginning and an end. Georges Buday spoke of ‘the fullness of time’, by which he meant the coming together of a range of technological, historical, social and economical factors giving rise to the Christmas card industry. I am going to go out on a limb and predict a ‘perfect storm’ of factors that may herald its demise: a combination of new technology, effortless social media, economic austerity, environmental concerns, less leisure time and a decline in civility. The creative energy seems to be draining away from traditional-format Christmas cards as a mass medium of exchange and communication, and their days as an aesthetically designed product expressing an individual’s (or a corporation’s) taste, values and self-image may be numbered.

The V&A houses the national collection of greetings cards, with more than 30,000 cards from the earliest examples to the present day for all occasions including Christmas – you can search the collection here.