The Keats House Museum: Where Histories Intertwine

Situated not far from the south-west corner of Hampstead Heath, the Keats House Museum is tucked away on a residential street in its own small green oasis. Built in 1815-16, its main raison d’être is now firmly established as the celebration of the Romantic poet John Keats (1795-1821), who lived there for two years. The Culture Trip London examines what this charming museum can teach us about the various histories it preserves.

Origins – Wentworth Place and Rural Hampstead

The large building now familiar to us as the Keats House Museum was known to Keats as Wentworth Place, built for Keats’s close friend Charles Brown and the Dilke family, who were all able to live in the house by the grace of a central dividing wall that separated the interior of Wentworth Place into two distinct homes. Shockingly for us today, when Wentworth Place was built in 1815-16, it was one of the only buildings located on the road stretching between the nearby village of Hampstead and Hampstead Heath.

A watercolour displayed in the museum shows Hampstead Heath in the 1800s to be a completely vacant landscape, inhabited only by a couple of wandering cows. In the early 19th century, Hampstead was by no means considered to be part of the city of London, and in all senses offered an environment which was completely opposed to the cramped, dirty, bustling atmosphere of the city. Nevertheless, by the time Wentworth Place was built, Hampstead was beginning to be established as a modest cultural hub through the presence of the writers and thinkers who had moved there to seek inspiration in the surrounding landscape. Among these was the poet Coleridge, who was then living nearby in Highgate. It was this that first attracted Keats as well.

Tragedy and Salvation – Keats Arrives in Hampstead

A film shown in the basement of the Keats House Museum dismally relates that, in the early 19th century, one in three Londoners died of consumption, the infection of the lungs now more commonly known as tuberculosis. Keats had been personally affected by this shocking statistic in his own life even before moving to the village of Hampstead with his brothers, Tom and George, in 1817.

In 1810 their mother died from tuberculosis, and by 1817, George and John Keats were nursing their brother Tom, who was also suffering from the disease. In 1818 George Keats and his wife emigrated to America, eventually dying of tuberculosis many years later, and at the end of 1818, Keats’ youngest living brother, Tom, died with Keats by his side. It was this distressing tragedy which caused Keats to move to Wentworth Place as Charles Brown, fearing for Keats’ health, begged him to swap his relatively cramped lodgings in the village of Hampstead for the fresher rooms at Wentworth Place. It is possible that the insistence of his friend helped to prolong his life. Keats moved to Wentworth Place in the same month that his brother died, renting a bedroom upstairs and a parlour downstairs.

From Surgery to Poetry – Keats’ Turning Point

By the time Keats moved to Wentworth Place he was set on an occupation as a poet. It may come as a surprise even to his most ardent admirers that he was actually firmly proceeding in a very different direction just a couple of years earlier. Keats became qualified as an apothecary surgeon in 1816, at the impressive age of 20, and intended to apply for membership to the Royal College of Surgery the following year.

A cabinet in the museum’s Brawne Room showcases the grisly artefacts which represent this unexpected part of the poet’s life: a large surgical saw and a porcelain container for leeches gleam alongside Keats’s own surgical notebook which is concentrated with illegible medical scrawl. Being aware of Keats’s training as an apothecary surgeon certainly adds another dimension to the image of his person, granting a sort of stabilising weight to this Romantic figure, so often depicted gazing wistfully into passing clouds.

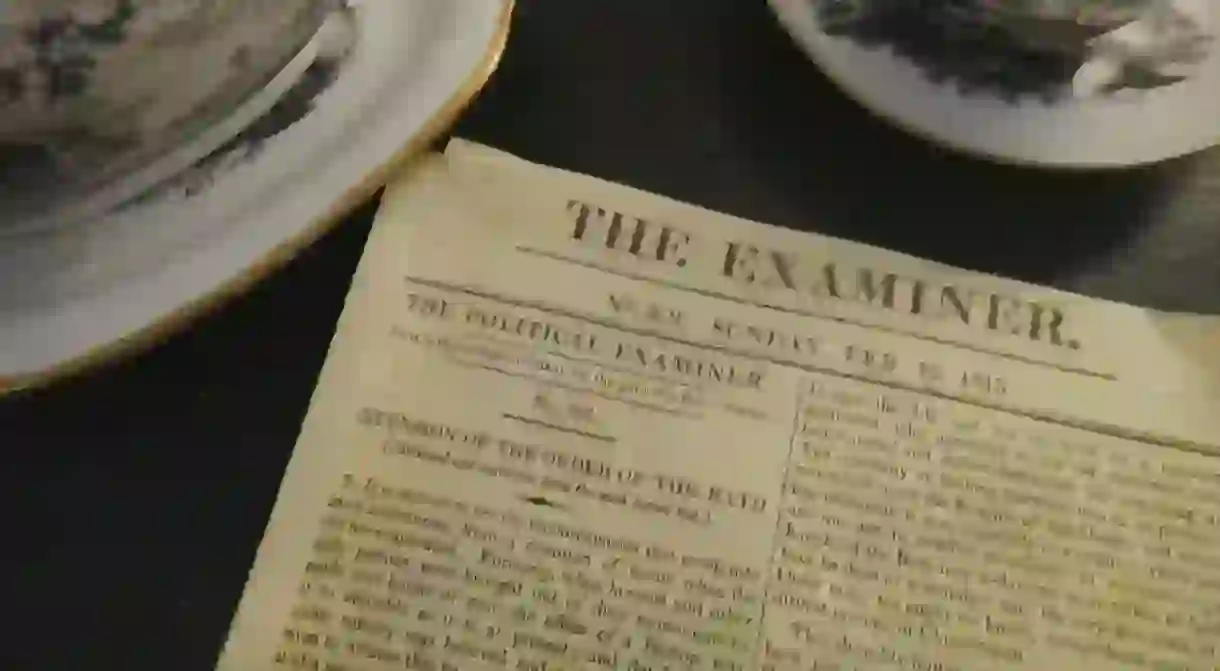

Nevertheless, despite the seeming unlikelihood of Keats’s dual interest in leeches and verse, another artefact in the cabinet testifies that he pursued them simultaneously: a copy of the edition of The Examiner in which Keats’ first published poem appeared sits in the corner. The influence upon him of this success largely contributed to his break with his surgical career, a decision which also reversed his hope of financial security.

![Joseph Severn, Portrait of John Keats [reading in his parlour at Wentworth Place]](https://cdn-v2.theculturetrip.com/10x/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/john_keats_portrait_by_joseph_severn.webp?quality=1)

Diving Walls – Fanny Brawne

A year after Keats moved into Wentworth Place, the Brawne family moved into the other side of the house, replacing the Dilkes. The fervent love story which subsequently ensued between Keats and Fanny Brawne, the eldest Brawne child, is generally well known and though the museum does not elaborate excessively upon the details of their relationship, the very nature of the house highlights a certain aspect of it in a unique manner.

Walking the short distance along the corridor between Fanny’s and Keats’s bedrooms – a distance of just a few meters between these intimate spaces – the realisation that the dividing wall which ran through the house would have rendered this impossible is moving. Of course, the demands of 19th-century propriety would have kept the bedrooms of the opposite sex out of bounds in any case, but the ghostly presence of the dividing wall is emotionally significant because it seems to be symbolic of the barriers they faced in their relationship.

Always being so close and yet so far from reaching what they wanted, they became secretly betrothed in 1819, but could never become formally engaged or married due to Keats’s unstable income and subsequent premature death. The beautiful ring he gave her is still on display in her bedroom; the intimacy of which is felt even more so because we are permitted to walk around her room and peruse her most personal trinkets in a way which possibly no one else could have while she was alive.

Waking Dreams – The Odes

Despite the frustrations ultimately faced by Keats and Fanny, their blossoming love was a source of intense joy for Keats. Alongside this, perhaps not accidentally, 1819 was his most productive and poetically significant year, in which he not only wrote his marvellous poem The Eve of St Agnes, but also composed all of the Odes which significantly define his poetic legacy, from Ode to a Nightingale to Ode on a Grecian Urn.

After his death, Keats’s friends made various claims as to whether he wrote Ode to a Nightingale in the garden of Wentworth Place after being mesmerised by a nightingale singing in the plum tree. In any case, it is likely that Keats did much of his best work in the parlour he rented in Wentworth Place. It is now presented as a brooding, intense space, ripe for contemplation and packed with the great literary works that Keats owned and drew inspiration from.

Arterial blood – Illness and Death

One evening in February 1820, at around 11pm, Keats returned to Wentworth Place looking violently feverish. He told Charles Brown that he had caught a chill that evening by sitting on the outside of the coach – in order to save money, as the cost of the journey would have been much higher if he had sat inside it – whilst making the journey back to Hampstead. He was rushed up to bed, where he coughed up blood and uttered the heart-rendering words recorded by Charles Brown: ‘I know the colour of that blood;–it is arterial blood;–I cannot be deceived in that colour;-that drop of blood is my death-warrant;–I must die.’

The museum fully honours the gravity of this moment in its presentation of Keats’ bedroom. The bed – where Keats voiced his discovery that he too was afflicted by tuberculosis – is the dominating feature in the sparse and sombre room. Keats actually died in Rome a year later, but standing in the room in which he pronounced those desperate words is deeply affecting.

The Keats House Museum is especially captivating in the way it stirs up a real sense of the personal presence of Keats within it, from allowing us to gaze out of his bedroom window as he surely did, when he was well enough, to saturating the walls and corridors of the house with images of the people and places that filled Keats’s life, to displaying a posthumous memento made by his friend, Joseph Severn, who was with him at his death – a brooch containing Keats’s hair as the strings of a bardic lyre, the symbol also portrayed on his tombstone.

The attention paid to Keats’s personal experiences and tragedies by the Keats House Museum certainly makes visitors wonder if he would have lived a happier and longer life, married to Fanny Brawne, if he would have chosen the financial stability offered by his surgical training. But if he had, his name would have been washed away. Through his choices he unwittingly sacrificed his happiness for the legacy of a great poet.