‘Living With Buildings’: A Healthy Look at How Architecture Shapes Our Wellbeing

Wellcome Collection’s timely exhibition Living With Buildings examines how the structures around us affect our mental and physical health. Curator Emily Sargent discusses the power of good design, from Maggie’s Centres to Alvar Aalto’s sleek sanatorium, as well as the vital lessons we can learn from post-war housing.

Culture Trip: What are the key themes of the exhibition?

Emily Sargent: A residing theme is the way that architecture can make us feel looked after, which comes to the fore in our exploration of Maggie’s Centres [a network of drop-in centres across the UK that help those affected by cancer]. We commissioned a filmmaker to go to two of them – one in Manchester by Foster + Partners and one in Dundee by Frank Gehry – to talk to people who used those buildings, which was both fascinating and moving. I think that feeling of being taken care of and having a safe space to let go is really important. One of the users said, “This makes my life worth living,” and that’s a really big statement.

It’s also interesting talking to the staff, as many of them had previously worked in a clinical setting. One explained,“You get a different answer to the same question here,” and that’s what an environment can do – it gives people an opportunity to have a different response to the same question. Someone might ask “How are you?” in a sterile oncology unit and the answer might be very different if you’re sitting somewhere where you feel sheltered, looking out at a garden and drinking a cup of tea. Another patient from Dundee talks about the democracy and visibility of the Maggie’s Centres. You can see people having good days and bad days, which allowed her to have good days and bad days too.

CT: The exhibition also touches on historical examples of how public health issues were addressed. Are there any especially innovative designs that solved those problems?

ES: There’s an early 20th-century tuberculosis sanatorium, designed by the famous Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. Tuberculosis was a major public health concern at this time and the best hope for recovery was a stay at a sanatorium. Every element of Aalto’s design in Paimio responded to patient need. The building’s orientation was designed to wrap around the light, curved walls were introduced because they’re easier to clean, balconies were added so patients could take in fresh air twice a day, even the door handles were designed so you wouldn’t catch your cuffs on them. We have a bent plywood Paimio chair on display that he designed especially for the sanatorium, which is set at an angle that optimises respiration – the level of detail he went into was extraordinary.

CT: What other key highlights do you have on display in the exhibition?

ES: The great thing about having exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection is that you have access to all kinds of material that’s relevant to the same subject. To open the exhibition we have a handwritten manuscript of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, a Pissarro painting of Bedford Park in Chiswick and a Gursky photograph of Montparnasse in Paris, so lots of real treasures. But actually, the things I’ve enjoyed getting to know are the stories of the residents and their interactions with the buildings, such as Balfron Tower, or the people that used the Maggie’s Centres. It’s wonderful to get a sense of how the architecture of those spaces has made a real difference to their daily lives.

The biggest commission is a full-scale mobile health clinic, designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, which takes up the entire first-floor gallery. The Global Clinic is a collaboration with Doctors of the World, and the idea is once the exhibition is over, the clinic will be deployed in the field. We’ll build it in a day, as one of the principles of the design is that it’s flexible to transport and easy to construct. Currently, Doctors of the World are using tents, which obviously aren’t well insulated and not very durable. It’s also possible to email instructions to the nearest city with a CNC cutting machine to make the parts that can then be easily delivered. It was key that it was also a beautiful thing – it’s not just solving problems with agility and making it easy to transport and build, but also that it’s welcoming.

CT: Another major part of the exhibition explores the rise and decline of tower blocks – the first attempts to build a modern and healthy utopian world in post-war Britain. What can we learn from these, and how do they differ from modern-day housing now?

ES: There’s a complicated discussion around whether tower blocks are a viable way to provide high-density, high-quality housing. What was at the heart of those developments was the principle of a decent place to live with community facilities, whereas now we’re operating in a way where we’re putting numbers and targets at the heart of building.

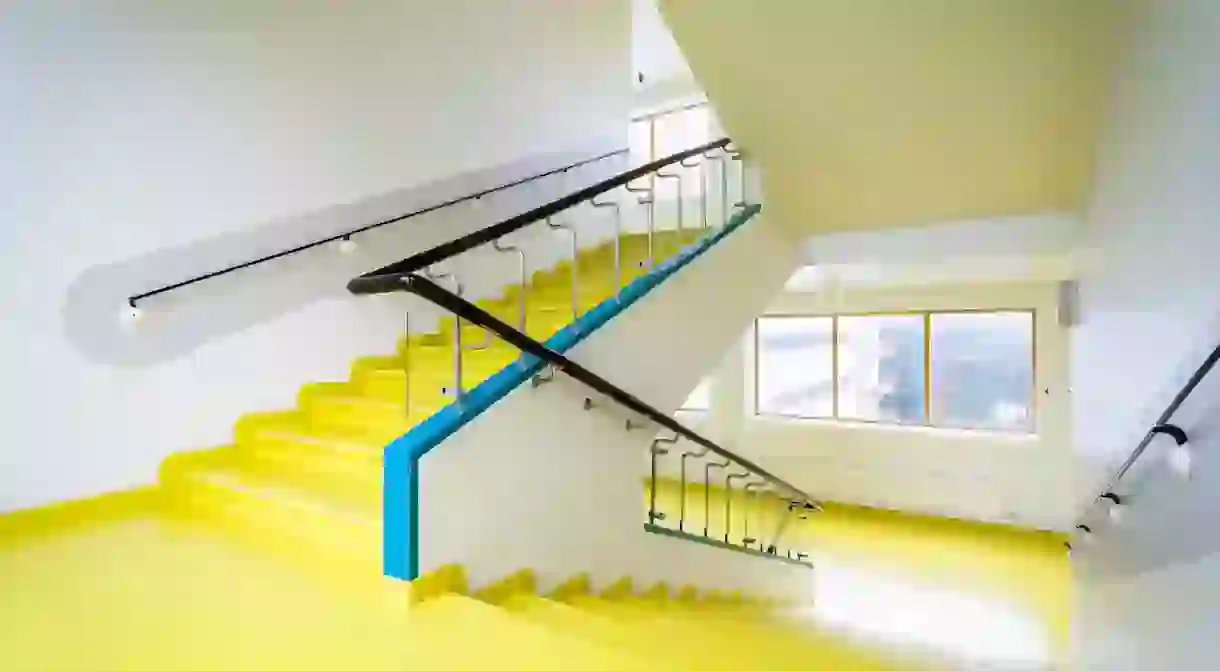

In the exhibition we feature Ernö Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower, a 1960s Brutalist building in Poplar. It was designed in an innovative way to adhere to the Parker Morris space standards, so they were well laid out, of a decent size and had dual-aspect views. Essentially what’s happened is they were built in an era when decent housing was for everyone and it was a priority. But then society changed, priorities changed and they weren’t maintained, as it was discovered that the upkeep of tall buildings is expensive, and so Balfron Tower is now in the process of being redeveloped for the private market. There are various things about their design, such as the space standards, that make them very enticing to private developers, so the people who live in high-rise towers now are either extremely wealthy or people in social housing.

We’re now having the same conversations we had around 50 or 60 years ago about urban sprawl, and this kind of new phrase around ‘place-making’ and creating a wider environment that feels good to live in. You find examples of that in surprising places, like Balfron Tower, where the principles that informed its design were around liberating green space, bringing the countryside into the city. You would build high so that you could have access to green space at ground level. I think it’s interesting to look back and see lots of different visions of the future, but I suppose it’s trying to take a moment, especially now, to think about people who are currently in need of social housing and don’t have easy access to housing, particularly in London. What happens next to them? Have we got to a point where we’re not prioritising health and the human experience at the centre of the buildings that we’re making? You can’t fault the post-war vision, even if it played out differently to their intentions.

Living With Buildings runs until 3 March 2019 at Wellcome Collection, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE.