William Morris: The Socialist Interior Designer Who Revived British Craftsmanship

‘I do not want art for a few any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few’; designer, writer, artist, poet, and early socialist, William Morris was one of the most important figures of the Victorian era. Credited with reviving many traditional, lost methods of production, he was one of the key driving forces behind the Arts and Crafts Movement, an enormously influential artistic phenomenon that spread across Europe, America and Japan, while the influence of his radical, anti-industrial ideas in both design and politics continues to be visible in the British cultural landscape today.

William Morris was born in 1834 in Walthamstow, then Essex, to a wealthy middle-class family; his father was a financier and his mother belonged to a landed bourgeois family. Morris enjoyed an idyllic early childhood, spending a great deal of time outdoors, exploring his surrounding land and the nearby Epping Forest — an affinity with nature that would play a large part in his later art — and harbouring a fascination with architecture from an early age.

In 1852, Morris left for Exeter College at Oxford University, with vague ambitions of entering the clergy. Whilst there, he became enamoured by the town’s medieval buildings, and began to take a growing interest in medieval art. In his first year, he would meet Edward Burne-Jones, who would later go on to become one of the most prominent of the Pre-Raphaelite painters. The pair grew close to a set of other young students who called themselves The Brotherhood (history remembers them as the Birmingham Set), all drawn together by a love of poetry (particularly of Tennyson, who was himself heavily influenced by the Romantic poets), medievalism and architecture.

The entire group were inspired by the writing of William Ruskin (who was known to champion the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late ’40s), in particular a chapter in his book The Stones of Venice entitled ‘The Nature of Gothic’, in which he used architecture as a means to reflect on the social, moral, and aesthetic health of society. Praising gothic architecture, whose roughness he took as evidence of the craftsman’s personality and freedom, Ruskin attacked modern industrial capitalism, criticising the division of labour between thinker and worker which led to the production both of incomplete, cognitively and spiritually impoverished human beings, and identical, soulless and inhuman ornaments through repetitive labour. Ruskin put forth a vision of a new breed of master craftsman, elevated to the status of artists, which would reunify the mind and the body. This brand of romanticism, and rejection of the industrialised world, would stay with Morris for life, and during his third year at Oxford, he and Burne-Jones would make a walking tour of the gothic cathedrals of Northern France.

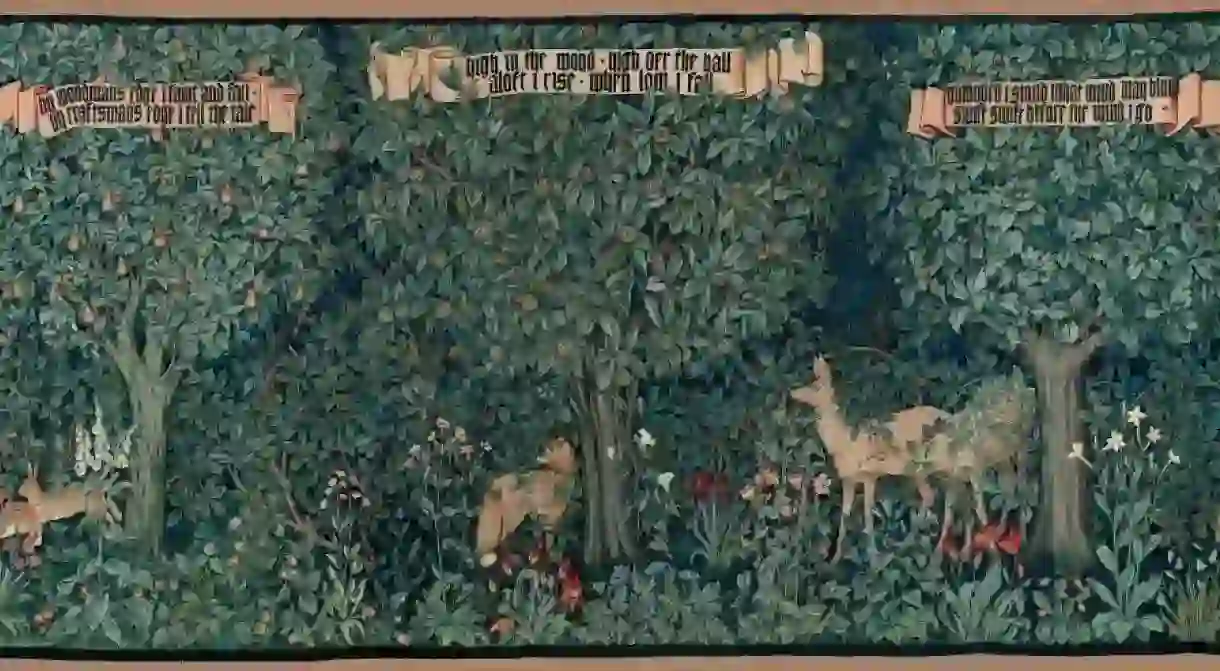

Having abandoned his plans to be a clergyman, Morris briefly flirted with the idea of becoming an architect, before landing on painting, after meeting the prominent Pre-Raphaelite painter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, through Burne-Jones. He moved to London after graduating (a city that fascinated him but which he saw as a ‘spreading sore’ upon the English countryside), taking up a flat in Bloomsbury with Burne-Jones, for which he designed medieval-style furniture painted in Arthurian scenes — very unfashionable at the time. A short while later, he would design and build a house and gardens for himself with the cooperative effort of The Brotherhood and Rossetti. Named the Red House, the building rejected modern architectural standards, instead inspired by neo-gothicism. Morris was responsible for the interior design, creating medieval-style floral embroideries and tapestries, while inviting his friends to paint murals of rural medieval scenes, inspired by Arthurian stories and Chaucer’s writings, on the furniture, walls and ceiling.

In 1861, Morris founded his own decorative arts company along with several of his friends including Rossetti and Burne-Jones (then called Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.), with the aim of putting Ruskin’s reformist vision of production into action, creating affordable art and elevating the decorative arts to the realm of the fine arts.

Morris would abandon his painting at this point, instead focusing on interior design. In 1862, he would design his first wallpaper, the items for which he remains most famous today. His designs took the natural world as their inspiration, their motifs sourced on the plants he encountered on walks — his first design, Trellis, was inspired by his house’s rose trellis — saying that ‘any decoration is futile… when it does not remind you of something beyond itself’.

http://instagram.com/p/BKyFvDiDPGB/?taken-at=436502

Over the next decades, Morris would commit himself ever further to medievalism. In 1875, his decorative arts company was consolidated into simply Morris & Co., with him as the sole owner. Rejecting the modern world and industrial means of production, Morris would spend long periods of time researching and personally mastering pre-factory methods. Disgusted with heavy levels of pollution, he refused to use chemical dyes, instead championing the return to organic methods, using natural materials which would give brighter pigments, reminiscent of the limited colour palettes in medieval art.

He is particularly well-noted for his revival of traditional British textile arts, in needlework, embroidery, carpet-knotting, weaving, and woodblock printing, but he also designed and produced furniture, stained-glass windows, tiles, metalwork, and books, producing beautiful handwritten, illustrated manuscripts reminiscent of medieval texts.

http://instagram.com/p/BGZMu7nNkIb/

By the 1880s, Morris was a renowned figure, his designs the height of fashion with the middle and upper classes despite his vision for accessible, anti-elitist art. His success would lead to the foundation of the wider Arts and Crafts Movement in the 1880s, which became the dominant force in British design through to the 1910s, its ideals influencing everything from architecture to painting, enamelling to ceramics, leatherwork to lacemaking, and spreading across Europe, North America, and Japan. Between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 130 Arts and Crafts guilds, associations and artistic communities were founded, disseminating the rejuvenation of the lost craft methods Morris had revived, and creating a strong generation of artisan craftspeople.

From the 1880s until his death in 1896, however, much of Morris’s attention was taken up by a new-found socialism. Having insisted throughout his career on learning the practical techniques of production, Morris had seen first hand the proliferation of poverty and poor living conditions amongst industrial workers. In 1883, he joined the Democratic Federation, Britain’s first socialist party, and began writing, lecturing, and campaigning on socialism the following year, founding the Socialist League in 1884 following internal schisms in his former party. While inspired by a sense of injustice in the profound level of inequality in society, Morris’ aestheticism was also always evident in his socialism, arguing that ‘so long as the system of competition in the production and exchange of the means of life goes on, the degradation of the arts will go on’. Reflecting the influence of Ruskin upon his thought, Morris would argue that ‘nothing should be made by man’s labour which is not worth making; or which must be made by labour degrading to the makers.’

http://instagram.com/p/BJYp_z4gSB6/

Over the next few years he would use his wealth to keep unprofitable socialist newspapers and periodicals afloat, and in 1890 published his novel News From Nowhere. The novel follows its narrator, Socialist League member William Guest, who falls asleep in the dirty, sooty, industrialised Victorian London and wakes up in a pastoral socialist paradise; imagining a moneyless society filled with beautiful, healthy people and beautiful goods produced for the love of labour rather than financial incentive, News From Nowhere is a reflection of Morris’ vision both as designer and radical socialist, and is considered one of the most important works in science fiction and utopianism in English literature. At the time of his death, Morris was considered primarily as a poet — he had been offered but refused the post of Poet Laureate after the death of Alfred Tennyson in 1892 — just another facet to this extraordinary, enduringly influential figure in British literature, design, and politics.