These Six Amazing Unbuilt Landmarks Could Have Changed Moscow Forever

The Design Museum in London is marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution with its latest exhibition, Imagine Moscow: Architecture, Propaganda, Revolution, opening on March 15. It shows the idealistic vision of the Soviet capital, envisaged by a bold generation of architects in the 1920s and early 1930s. Featured projects include the Palace of the Soviets, planned to be the world’s tallest building, and Cloud Iron, a network of striking horizontal skyscrapers.

The exhibition focuses on six of these never-realised works, all planned to be located near Moscow’s famous Red Square. After the October Revolution, there was a desperate search for an original architectural language to break from the Tsarist past. Architects aimed to reinterpret the old idea of the city by using new symbolism, designing new monuments and institutions, and building factories, theatres, communal housing and ministries. These dreamlike projects suggest an alternative reality for a series of sites around the city, offering a unique insight into the Soviet culture of the time.

Eszter Steierhoffer, curator of Imagine Moscow has said: ‘The October Revolution and its cultural aftermath represent a heroic moment in architectural and design history. The designs of this period still inspire the work of contemporary architects, and the radical ideas in the exhibition remain highly relevant to cities today. Imagine Moscow brings together an unexpected cast of ‘phantoms’ – architectural monuments of the vanished world of the Soviet Union that survive in spite of never being realised.’

Presented through plans, models, reproductions and projections, here are the six unrealised projects on display:

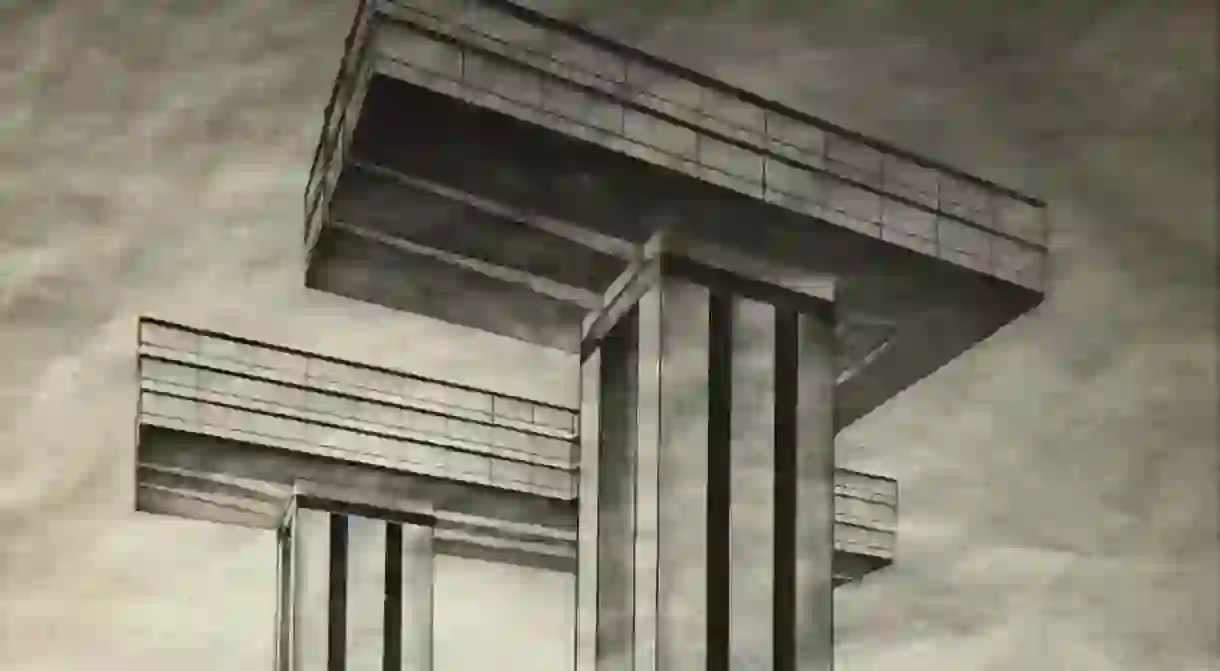

EL Lissitzky’s Cloud Iron (1924)

Lissitzky‘s vision for this ultra-futuristic design was a series of eight lightweight horizontal skyscrapers. Lissitzky’s plan addressed Moscow’s pressing issue of overcrowding and the inadequacy of its public transport by linking upper-floor office spaces to living accommodation, while also creating new tram and metro stations on the lower floors.

Boris Iofan’s Palace of the Soviets (1932)

Probably the most well-known scheme of all is Iofan’s winning entry for the Palace of the Soviets competition, which was an incredibly ambitious design. With a towering 100-metre statue of Lenin on top, it was set to be the tallest building in the world, beating the Empire State Building in New York.

Located close to the Kremlin, the Palace was conceived to replace the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Work began in 1937 but was soon brought to a halt due to the Second World War and the consequent German invasion in 1941. Oddly enough, its foundations were turned into the world’s largest outdoor swimming pool for a time, but in 1995 a complete replica of the cathedral was built to replace the previous version, as if it had never been destroyed.

Nikolai Sokolov’s Health Factory (1928)

Exploring the theory of the ‘living cell’, a common theme in architecture of the period, Sokolov created a design for the Health Factory – a retreat on the coast of the Black Sea – which consisted of individual capsules for isolated rest, and a communal hall for eating and other group activities.

Nikolai Ladovsky’s Communal House (1920)

Designed to revolutionise the traditional family structure, Ladovsky’s design for the Communal House became an early and iconic example of the Soviet idea of communal living. Ladovsky’s unique spiral design cleverly and subtly merged individual living units into one united space, alluding to symbolism of progress.

Ivan Leonidov’s Lenin Institute (1927)

This incredibly vast library, complete with planetarium, was designed to educated the new Soviet man. A huge tower served as motorised book storage, while the circular volume of the building enclosed the auditorium. State-of-the-art technology and advanced engineering was key to the project; the complex was going to be linked to Moscow via an aero-tram, while also providing the ability to communicate with the rest of the world via a powerful radio station.

The ‘Narkomtiazhprom’ building by the Vesnin brothers, Ivan Leonidov and Konstantin Melnikov (1934-1936)

This large-scale piece of architecture was going to occupy a prime site of around 10 acres directly opposite the Lenin Mausoleum, which would have housed the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry. While many firms entered the design competition (predominantly Soviet architects), no winning design was ever selected, but the proposed designs by the Vesnin brothers – Leonidov and Melnikov – are on display. These outstanding examples demonstrate the type of architecture that was set to shape the new industrial landscape of the Soviet Union.

The exhibition contains large-scale architectural plans, models and rarely seen drawings, which are placed alongside propaganda posters, textiles, porcelain and magazines of the time to contextualise the transformation of a city re-born as the new capital of the USSR, and the international centre of socialism.

Imagine Moscow: Architecture, Propaganda, Revolution will open run from March 15 – June 4, 2017. To book, click here.