8 Spectacular Unrealized Architectural Projects

From unrealized structures to entire unbuilt cities, there’s something spectacular about architecture that never was. In considering the power of architectural design – from megalomaniacal political plans to sublime edifices of arresting beauty – we profile eight unrealized projects throughout history.

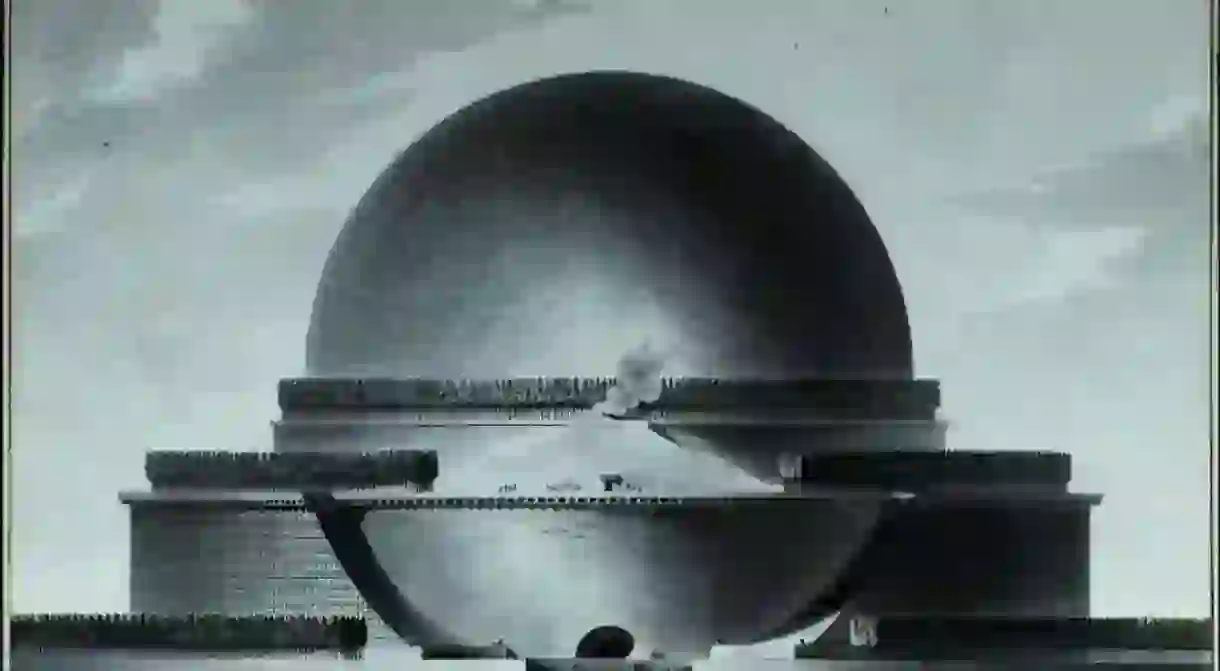

Cénotaphe à Newton (1784), Etienne-Louis Boullée

One of the most arresting architectural projects envisaged to this day, Etienne-Louis Boullée’s (1728-1799) Cénotaph à Newton is a colossal memorial honoring English scientist and mathematician, Isaac Newton. Compelling and grand, the sphere is enforced by two barriers and surrounded by three levels of cypress trees, which serve to clarify the building’s tremendous magnitude. Newton’s sarcophagus was to be placed at ground level; during the day, controlled levels of sunlight would evoke the illusion of a starry night above the tomb, and at night, a large lantern would radiate beams of light through the shadows. The Cénotaph is paradigmatic of Boullée’s architecture parlante (‘talking architecture’), which postulated that a building’s design should be free of embellishments to outwardly express its fundamental purpose. Here, the sphere symbolizes perfection and eternity; staircases between exterior levels create a ziggurat-like outline; varying sunlight intensity alters the sphere’s perceived gravity; strategic perforations in the sphere offer views of planets and constellations – the project in its entirety nods to Newton’s lifetime of work and the building’s status as a mausoleum.

Grand Hotel Attraction (1908), Antoni Gaudí

By the early 20th century, Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí was garnering international attention for his avant-garde visions of Modernist design; the Sagrada Familia (1882 -) was well underway, as was Park Güell (1900-1914) and Casa Milà (1906-1912), transforming Barcelona’s skyline with futuristic edifices belonging to a never-before-seen organic neo-Gothic theory. An ocean away, New York City contrastingly favored the classic Beaux-Arts aesthetic of 18th and 19th century France. Akin to a celestial sandcastle, Gaudí’s proposed Grand Hotel Attraction would have been a striking addition to the Big Apple’s panorama. Had it been realized, this building would have been the tallest in the United States at the time. The proposed Lower Manhattan-based skyscraper was to feature a star-like sphere observatory at the top of the tallest tower, accommodating 30 people at a time for unparalleled views of the city. The building’s expansive interior would include a theater, lecture hall, exhibition space, guest rooms, and six floors of restaurants. Gaudí never commented on why the Grand Hotel Attraction failed to materialize; one theory suggests that Gaudí’s poor health led him to cancel the project, while another speculates that the project was abandoned due to a political disagreement between the architect and his investors.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wD0f_56hSTc

Plan Voisin (1925), Le Corbusier

Visionary Swiss architect, artist, writer, and designer Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was one of the leading pioneers of modern architecture. Inspired by Bauhaus principles and the Industrial Age’s profound impact on contemporary culture, Le Corbusier advocated for design utility and new architectural strategies that would improve the quality of urban life. In 1925, the architect conceived of a radical plan to practically level Paris’s 3rd and 4th arrondissements – neighborhoods with notable architectural and historical significance – replacing nearly everything north of the Seine with uniform high-rise cruciform towers (though he did intend to preserve the area’s most precious landmarks). While Plan Voisin may sound heinous to modern-day Francophiles, Le Corbusier’s Paris was ravaged by poverty and disease from poor sanitation and overpopulation. Plan Voisin would create a new Paris; a spacious, accessible city with clean air; pollution and disease diminished; the people well and cared for. While Le Corbusier’s plan never materialized, it highlighted the imperative relationship between practical urban design and human welfare, alongside the concept that architecture is a lived experience – one that permeates and guides human life on both a physical and spiritual level.

The ‘Ideal City’ of Chaux (c. 1775), Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

Alongside Boullée, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806) was one of the most influential architects of the 18th century. Ledoux became popular amongst the French elite for his visionary renditions of traditional neoclassical design, but in 1775 he began the project that would serve as his greatest legacy. He was to redesign the original saltworks at the Salines de Chaux – but his plans radiated far beyond a single building. Linking the towns of Arc and Senans from a perpendicular direction (one axis already existed), he conceived of a self-sufficient utopian city around the Saline Royal, complete with an updated factory, housing for workers and their families, a cemetery, and a temple. Ledoux’s Enlightenment-era philosophies were deeply integrated into his architectural theory; his progressive designs would ensure the health and happiness of Chaux’s inhabitants through plenty of communal space, access to nature, and aesthetic alignment that residents could internalize. In redesigning the original medieval site, Ledoux managed to complete about one half of his plan – and the realized buildings serve as the first feats of industrial architecture.

Welthauptstadt Germania (1943), Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer

One of history’s most absurd urban renewal projects, Welthauptstadt Germania (‘World Capital Germania’) was a maniacal project planned by Adolf Hitler and his principal architect, Albert Speer, between c. 1937 and 1943. The plan devised a completely renewed Berlin that would suit the perceived ‘grandeur’ of the Thousand Year Reich; Hitler intended to build several colossal structures comparable only to those of the great ancient empires. The plans included a north/south axis linked to new railway stations, an olympic stadium that would present Nazi principles to an international audience, and the project’s magnum opus: the Große Halle (‘Great Hall’) – the dome of which would be 16 times the size of the dome atop St. Peter’s Basilica. Aside from concerns about the psychology of Hitler’s dwarfed physical size in juxtaposition to such architectural magnitude, Berlin’s marshy foundation posed a threat to the depraved duo; thus they built the Schwerbelastungskörper (‘heavy load structure’) to test the integrity of one proposed site, which remains a haunting relic of Nazi society to this day. Had it been realized in its entirety, Welthauptstadt Germania would have been the largest city in the world.

The Panopticon (c. 1791), Jeremy Bentham

One of the most philosophical works of architecture ever conceived, the Panopticon served as a new form of penitentiary devised by 18th century English social theorist Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). Its cylindrical design was intended to foster the capacity for a singular watchmen at the center of the building to keep tabs on every inmate within one prison complex – without any of the inmates knowing when they’re being observed. This visual omnipresence would create a state of paranoia amongst the inmates, which would subsequently increase their self-control at all times, regardless of whether they were being watched in actuality. Theoretically, this form of psychological architecture could also be employed within hospitals, schools, and asylums. Bentham spent many years refining his design, and many more in negotiations with the government and with landowners to realize his project. The prison was never built in his lifetime, but the concept sparked a discourse surrounding the power of architecture to enforce discipline and surveillance. Since Bentham’s death, several Panopticon-like structures have been built in Cuba, Portugal, the United States, and the Netherlands, but none hold true to Bentham’s original design.

The Palace of the Soviets (1941), Boris Iofan and Vladimir Shchuko

Between 1931 and 1933, Joseph Stalin held an architectural competition for a new municipal building called the Palace of the Soviets to be erected where the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour once stood in Moscow. Some of history’s most famous then-contemporary architects submitted proposals, from Le Corbusier to Auguste Perret and Walter Gropius. However, the winning design was a bizarre convergence of architectural styles by Boris Iofan and Ivan Zholtovsky. In March of 1934 the site was cleared for construction, and by 1937 construction had commenced. If it were realized, the Palace of the Soviets would have been the largest building in the world. Parts of the building’s steel frame were already assembled when the structure was taken apart for reuse in 1941 when the Germans invaded and materials were better repurposed for infrastructure like forts and bridges.

EPCOT/Project X (1966), Walt Disney

Internationally known as one of multiple theme parks comprising the Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida, Walt Disney originally conceived of EPCOT (the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) as a functioning utopian ‘city of the future’ near Los Angeles. Also referred to as Project X, EPCOT’s epicenter would have been marked by a 30-floor hotel, surrounded by an aesthetically-pleasing municipal building beneath an all-weather dome, clean and efficient factories, suburbs, and reliable methods of public transportation. While EPCOT was never realized as an official urban space, the East Coast theme park erected in its honor in 1982 bears several of the proposed city’s design elements, from the geodesic sphere to a radial plan.