Read 'The Runner', a New Book About Isolation and Self-Discovery

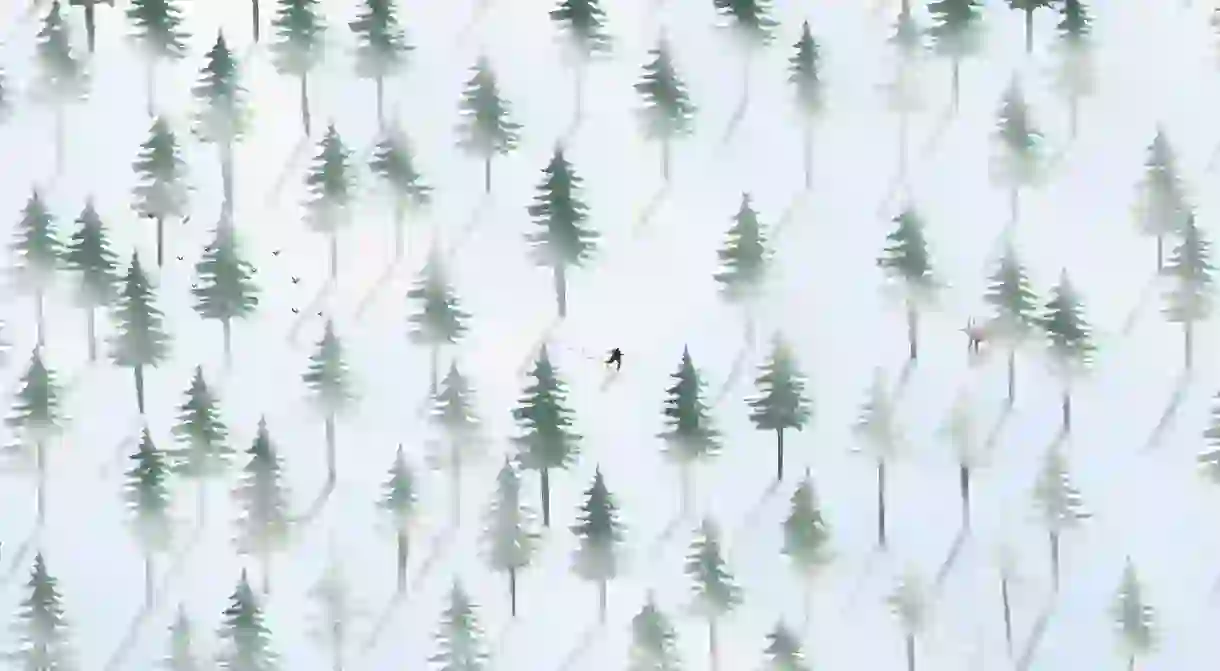

Buckling under the weight of pressures from his coach and his personal life, runner Markus Torgeby dropped everything to live alone in the wilderness of a Swedish forest. For four years, Torgeby existed off the bare minimum and focused simply on running, in the hope that he would give his life the direction he craved. Read an extract from The Runner below.

I walk through the forest. The air feels icy and damp and the sky is dark with heavy clouds. I’m wearing Mum’s white raincoat and I’m walking fast. I hear a branch snapping behind me and I prick up my ears as I turn round.

I see nothing. I hear nothing. Perhaps it was just an elk? Perhaps it was something else?

The adrenaline is pumping, I can’t walk any longer. I start running, I can’t resist the impulse, I’m just reacting. I accelerate until I am running as fast as I possibly can. It doesn’t help, I am getting more and more frightened. Jesus, please help me!

I tear off the white raincoat. I don’t want to be visible in the dark. I roll it up and push it under my sweater. I hide under a fir tree where I crouch down, waiting. I am quite still. Nothing happens. It feels safe to be leaning against the tree. I stay put. After what seems like an eternity, I crawl from my hiding place and start walking home. It’s tough to leave the tree.

I run round Norsjön towards Helgesjön, see the Åreskutan mountain 15 kilometres to the west, tripping through marshes and wading across tiny streams. The air is cold and I am wearing a thin woolly top and a pair of blue tights that I was given by that shouting trainer of mine. I am wet up to my knees, my hands are cold, but my body is kept warm by all this exercise.

I haven’t seen another human being in three weeks. I am talking loudly to myself and sing songs so that I can at least hear my own voice.

I have never spent so much time on my own. It feels strange. Time moves more slowly. I breathe more deeply, and I can feel my heart beating.

The sun is high in the sky and everything is actually quite simple. I’m not freezing. I’m not hungry. The mosquitoes are gone, I’m no longer itching, but I have no peace. I have nothing to do.

I see a birch and suddenly have the urge to climb it. I heave myself up on to a branch and climb higher and higher, branch after branch until I can’t go any further. I stop with my foot lodged in the fork of a branch.

The tree sways in the wind. I look out across the valley. I see the shifting colours of the fir trees. I close my eyes and disappear into myself.

I don’t read any books here. I don’t listen to the radio. I don’t watch the TV. I don’t feed on other people’s opinions, don’t have to fit into any other context.

I can’t bear being with people; everyone keeps on talking, too many words and opinions that aren’t based on anything. Everything is surface, no depth. So many answers, endless debates on television, I wish that everyone would just shut up.

I can’t find any direction in the ordinary plastic existence, I think everything seems a waste of time – I don’t want to have to choose between different kinds of shit, I want to choose between good and bad, or good and evil, between life and death.

I want my choices to have consequences – if I make the wrong choice, it should really hurt.

Am I running away from something? I stand there until my foot starts hurting. When I get back home again, I have run 25 kilometres, my legs feel weak. I take off my wet clothes and hang them on the line, tie the shoelaces together and hang up the shoes. They smell of marsh and earth.

It’s the afternoon. The sun is tired, but the light is warm, and I run from the Slagsån up to the marsh below the heights of Romohöjden. On the top of Åreskutan the snow is sticking. I run across the marsh and my legs feel light.

I run in giant strides across the mountain slopes, all the way down to the river Indalsälven and past the Ristafallet waterfall. I continue down the path along the river and get back on the hill, three kilometres of steep uphill running. I move effortlessly and come back to the marsh with the sun on my back.

Then I hear the call of an elk. I stop. After a while, I hear another elk answering a bit further away. I put my thumb and index finger across my nose and make a call of my own and both elks answer.

They are both quite close and I stand still. At last they come out onto the marsh with 30 metres between them. I don’t move. Nor do the elks, and their big ears are pointing towards me like satellite dishes. We form a triangle – the bull, the cow and I. The elks have got the evening sun in their eyes and the wind at their backs. Their legs are long and thin, and they look strong.

I run on, and so do the elks. There are crashing sounds from the forest as they disappear. When I reach the lake Helgesjön I take off my clothes and jump in, and swim around until the mud and sweat has been washed away.

I rub my armpits with sand and walk naked through the forest all the way back home to the tent. I put on my underclothes, my thick socks and hat. Steam comes from my mouth when I breathe out. I go out into the forest to collect birch bark and fine twigs to use as kindling. I split some logs for when the fire has taken. I build the fire up with bigger and bigger branches. I keep the fire going until it’s warm inside the tent, and I warm away the dampness from the canvas.

The forest is silent. My face is warm from the fire. Outside there’s a wall of darkness. I eat crispbread with butter and drink some warm water, let the fire burn down and go to bed. I write down the events of the day in my diary. I watch the stars through the smoke vent. I like lying there wrapped up in my sleeping bag, feeling the cold night air against my face.

The Runner: Four Years Living and Running in the Wilderness by Markus Torgeby, is published by Bloomsbury Sport, 2018.