Retracing The Art Of Antoni Tàpies, From Surrealism To Pop Art

One of the most influential and enigmatic artists to come out of Catalonia, Antoni Tàpies transitioned from his surrealist origins to a modern artistic pioneer whose mission involved making art as an interpretable work rather than an object of simple ornamental value. A self-taught painter, sculptor and art theorist, Tàpies produced an extensive body of work that ranged from textured canvases and lithography to graphic work and mixed media.

Tàpies was born in Barcelona in 1923 to a middle-class nationalist Catalan family who encouraged him to become versed in the fields of literature and art. The city was also where his first inspirations took form in the likes of Ibsen, van Gogh, Dostoevsky, Picasso and Kandinsky. While he was recovering from a severe lung disease, he started experimenting with drawings and self-portraits with disfigured features that influenced his later famous motifs of textured crosses and cryptic symbols.

His trajectory as a painter began as a teen, where the Catalan art magazine D’Ací i D’Allà (From Here and From There) connected him to the Surrealist and Dada movements. As his style began to take shape, it evoked the elementary essence of childlike drawings and the abstract expression from artists such as Joan Miró and Paul Klee, cultural referents for Tàpies. His early works, like Great Painting (1958), consisted of collages on cardboard and incorporated a range of everyday materials into his pieces, such as string or torn up paper — techniques that began to distinguish his artistry and characteristic methods.

During the ’50s, Tàpies’ international recognition grew, as he evolved into a more informal artist — he was one of the first to begin incorporating non-artistic materials such as marble dust and clay into his paint. This approach echoed the Arte Povera movement in Europe and Abstract Expressionism in the United States, all of which encouraged the use of different materials and textures, a decisively innovative concept at the time.

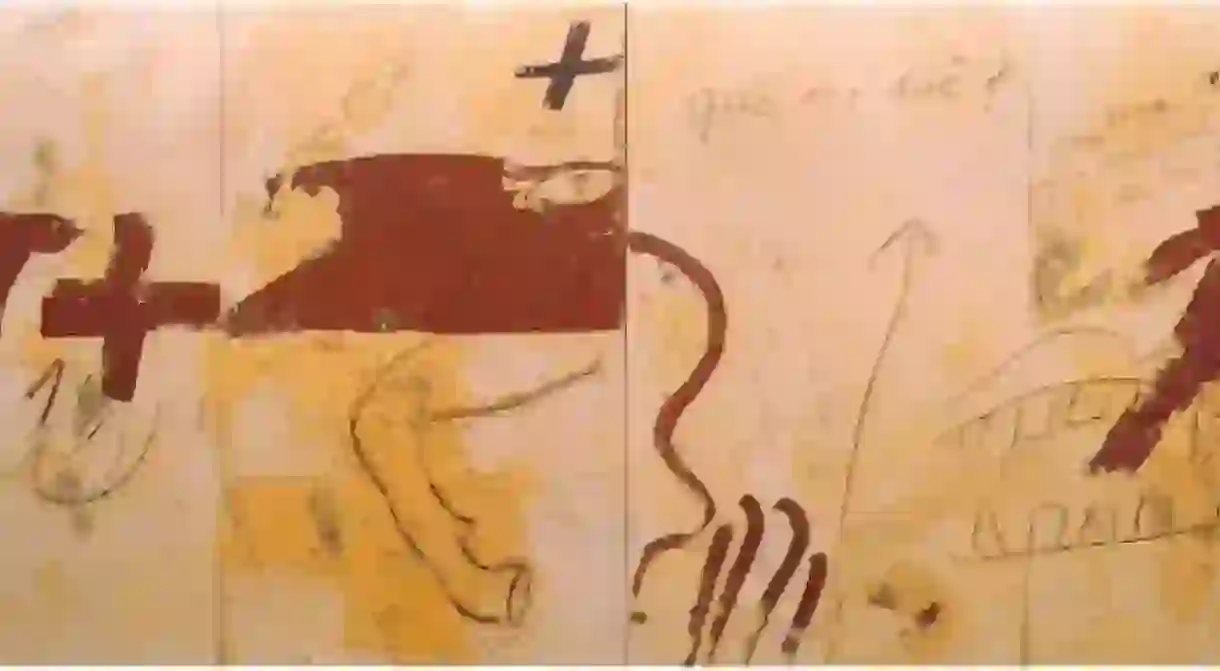

This signature style, also described as ‘pintura matèrica‘ (material painting), is reflective of Tàpies’ growing interest in dissecting the material world and all its coherent meanings, resulting in a culmination of recurrent themes that negated a predetermined structure and form. Instead, Tàpies was concerned with the juxtaposition of lettering and symbols, which he refused to clarify, encouraging the spectator to decode their meaning. Here, it is certain details and objects that gain an individual power and value by themselves in fully removed contexts.

Although Tàpies was dedicated to interrogating universal truths and motifs, much of his work also reveals a dialogue between his personal identity and the spirit of Catalonia as a whole, marking an intertwinement of art with history. In 1969, he explained to art critic Michel Tapié:

‘My first works of 1945 already had something of the graffiti of the streets and a whole world of protest — repressed, clandestine, but full of life — a life which was also found on the walls of my country.’

During the ’70s, it was this rebellious spirit with which his work is permeated. Images of political concern are a recurrent theme and emblematic of Tàpies’ opposition to dictator Francisco Franco’s regime. In The Catalan Spirit (1971), the yellow background and four bloody crimson stripes of the Catalan national flag are emblazoned with graffiti-like political script, including words such as ‘culture’, ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’.

Companys (1974), also prominent with striking, powerful splashes of color, mourns the execution of republican political leader Lluís Companys in 1940 by Franco, a sentiment that strikes at the core of Catalan spiritual identity. These types of works reveal the expressive power of protest of a nation that is both fragile and resistant at the same time. In essence, in his comment on Catalan existence and how he perceived his immediate world also informed Tàpies’ reflection on human relation and endurance on a wider scale.

Clearly, Tàpies’ political empathies influenced his work, and after the Second World War and the dropping of the atomic bomb in 1945, the events sparked his interest in foreign objects — specifically, ‘matter,’ which in his more mature work is where his more recognizable style comes to surface. Tàpies developed his techniques related to matter art, a movement concerned in the richness of textures and the evocative power of material elements.

With the rise of Pop Art and Conceptualism from the 1970s onwards, Tàpies began to move into more expressive spheres of art where visceral objects took on a whole new meaning. He began incorporating larger, everyday items in his paintings, such as pieces of furniture, ladders, buckets or blinds, where he explores the mystically coded meanings of objects. In Desk and Straw (1970), a deteriorated wooden desk acts as the canvas of the work itself piled with a bundle of straw, and in Rinzen (1993), a hospital bed symbolizes the instability of the Bosnia war and evokes a place of light and darkness, life and death and beginning and ending.

A lover of ambiguity, Tàpies was intent on deciphering the meaning of nature and uncovering beauty in the most ordinary things. Largely inspired by Eastern philosophy, his later work also delves into the realm of the sacred and explores his concern with consciousness and thought and the duality of man and nature. Here, man’s most vital queries are exposed: vitality, death and sexuality. On large canvases, he illustrated the passing of time and nature, depicting his youthful experiences in the Montseny landscape, exemplified in paintings such as Suite Montseny 9 (1993), and employed techniques with graffiti, varnishes and spray, portraying incomplete body parts and reiterating the fragility of the human body.

When his museum Fundació Antoni Tàpies opened in Barcelona in 1990, he said: ‘My illusion is to have something to transmit. If I can’t change the world, at least I want to change the way people look at it.’

By Julia Solervicens