What Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Can Tell Us About Truth

Friday, 3 August 2018 marks the 10th anniversary of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s death. At a time when alternative facts and fake news are commonplace in public discourse, the Russian writer’s commitment to objectivity is a refreshing reminder of the existence of truth.

A 2017 CNN commercial displays a picture of a red apple against a white background. “This is an apple”, the narrator states. “Some people might try to tell you that it’s a banana. They might scream ‘Banana, banana, banana’ over and over and over again. They might put BANANA in all caps. You might even start to believe that this is a banana. But it’s not. This is an apple.” CNN’s advert – witty, clear and cutting – is a pointed rebuttal of the culture of fake news and alternative facts, propagated by certain media outlets and individuals in Europe and the USA. It is a timely attempt to reassert the authority, and indeed existence, of truth.

Writer and critic Michiko Kakutani cites the CNN advert in the opening chapter of her new book, The Death of Truth. Its Nietzschean title refers to the extreme relativism that is sweeping through public life in America and threatening the existence of objective truth. Kakutani’s book – playfully styled with a 1960s aesthetic – outlines the extent to which fake news has seeped into mainstream discourse.

“[I]t’s not just fake news,” writes Kakutani, “it’s also fake science (manufactured by climate change deniers and anti-vaxxers), fake history (promoted by Holocaust revisionists and white supremacists), fake Americans on Facebook (created by Russian trolls), and fake followers and ‘likes’ on social media (generated by bots).” Riddled with distortions, omissions, false equivalents and conspiracies, public discourse has become dizzying and chaotic, and the truth increasingly hard to discern. However, Kakutani’s book is not announcing the death of truth, but stating that it still exists.

Undermining truth is by no means new terrain for political powers. The two bloodiest regimes of the 20th century – Stalin’s Great Terror during the Soviet Union and Hitler’s Nazi Germany – engaged in the widespread falsification of news to dissolve the line between fact and fiction as a means of control. “The prose of the Communist Party and its journalistic organs was clogged with the ‘Nooyaz’ – the Newspeak – formed over dozens of years, great clots of language that had no purpose other than meaninglessness,” writes David Remnick in his colossal Lenin’s Tomb. Likewise, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt writes that: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e. the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e. the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

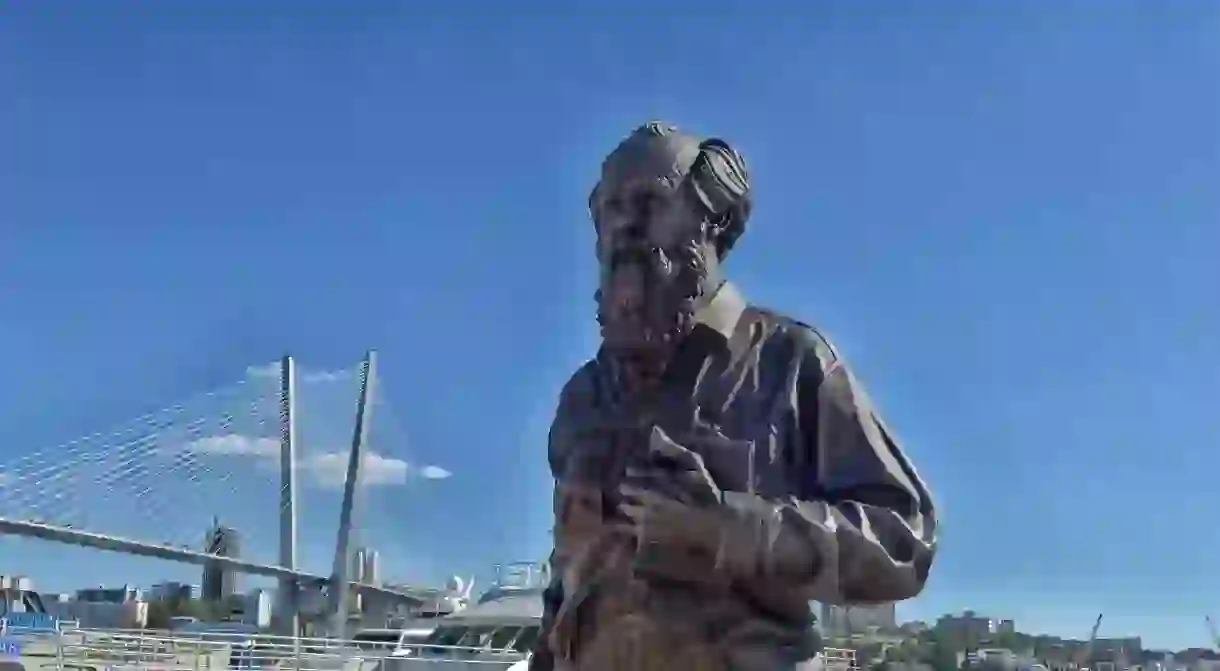

For Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian writer who exposed the oppressive regime of Stalin’s labour camps, the distinction between fact and fiction was not relative, but absolute. Born in 1918, the same year that Lenin’s Bolshevik army overthrew the Tsarist regime, Solzhenitsyn was a child of the revolution.

But in 1945, he was arrested and jailed for writing derogatory comments about Stalin. Sentenced to eight years in a labour camp, Solzhenitsyn experienced the brutality of Stalin’s regime, and documented it in his short but monumental 1962 novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Causing outrage among the Communist Party ideologues, Solzhenitsyn pulled back the curtain on the Stalinist regime, exposing the truth of its inhumane practices.

State-sponsored media was the primary tool in obscuring the truth about these practices. People were regularly airbrushed out of images, journals were routinely censored to align with Communist rhetoric and the USSR’s history books were rewritten to hide the scale of its countless abuses. But cracks in the Soviet Union’s mission began to form as the shiny optimism of their state propaganda no longer resonated with people’s reality.

“With the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” says Kevin McKenna, Green and Gold Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Vermont, “we actually get confirmation of what many, if not most, Russian people already knew. A large number of Russian people were aware as early as the late 1920s and early 1930s about the camps owing to the fact that so many of their close relatives were being arrested,” says McKenna. “These accounts, of course, were not publicised in the state-controlled news media, but news from friends and relatives about these arrests were most certainly commonplace – albeit in careful whispered form.”

Solzhenitsyn’s first book was so significant because it gave an authority to what people had long suspected – whispered hearsay hardened into credible reports. Though Solzhenitsyn was forced into exile during the Brezhnev years, he continued to be the spokesperson for prison life in the Soviet Union, publishing The Gulag Archipelago in 1973, which many credit as his defining work. Drawing from his own experience, as well as a litany of diaries, reports, official documents, interviews and accounts from other inmates, Solzhenitsyn tells not only his story, but the story of an era.

Positing testimony over subjectivity, Solzhenitsyn moved from being a novelist to a documentarian, drawing a firm line between fact and fiction. “There is no doubt in my mind that Solzhenitsyn would strongly object to the notion of a ‘relative truth’, much less the concept and practice of ‘alternative facts’,” says McKenna. Solzhenitsyn was preoccupied with objective, corroborated truth.

Ten years after his death, Solzhenitsyn’s account of the gulag experience remains the primary source on Soviet labour camps. His writing is both historically accurate and stylistically engaging, making it an invaluable and timeless source of truth. But in today’s world of ephemeral viral media and normalised moral relativism, could such an individual emerge as the defining voice of the era?

In January 2018, Michael Wolff published Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, described as a “scathing tell-all” that would expose the incompetence of both Trump and his administration. In the book, Wolff presents Trump as a largely ignorant political leader with an unstable temperament and an unhealthy love of McDonald’s; scandalous, but not altogether shocking revelations.

It sparked a similar response to when Solzhenitsyn published One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, in that it both outraged its subject and confirmed what the public had long suspected. However, Wolff’s research was a far cry from Solzhenitsyn’s fastidious source-gathering. As many critics argued, Fire and Fury was a rehashing of gossip and hearsay told from the perspective of an unreliable narrator.

Wolff’s methodology was born out of the New Journalism movement, a style of writing championed by Tom Wolfe in the 1960s and ’70s that is now commonplace among journalists. It favoured a more subjective and engaged style of reporting, encouraging the narrator to both report on and be part of the story. While not being untruthful, this method prioritises style over objectivity, intuition over insight; Solzhenitsyn, remarkably, offers all of these.

At the time, the New Journalism movement chimed with a growing hunger for relativism; it allowed more voices to be heard and orthodoxies to be challenged. However, as relativism has cemented itself deeper into the public consciousness, people have begun to conflate opinion and fact. “[R]elativistic arguments have been hijacked by the populist Right, including creationists and climate change deniers who insist that their views be taught alongside ‘science-based’ theories,” writes Kakutani. These false equivalents would have deeply offended Solzhenitsyn’s staunch belief in objectivity. “For Solzhenitsyn, the notion of ‘truth’ was not subject to any form of ‘relativism’,” says McKenna. “In his mind as well as in his writing, ‘truth’ was absolute and not to be bent or ‘used’ for one’s personal purposes.”

Upon winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, Solzhenitsyn said: “One word of truth shall outweigh the whole world”. For Solzhenitsyn – a deeply spiritual man – truth possessed a redemptive magic. In Russian, the world for truth – pravda – is associated with notions of justice and fairness, as well as fact. Striving for the truth was both a literary and moral pursuit.

In today’s frenetic media landscape, it is increasingly difficult for singular voices to cut through the noise. The burden of responsibility has now shifted onto the public, requiring everyone to become more engaged, discerning and responsible in how they consume media. In her introduction, Kakutani quotes Arendt from The Origins of Totalitarianism, in what is an eerily prophetic statement for our time: “In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true.”

The biggest threat to truth is not lies, but public indifference. Solzhenitsyn, through his meticulous research, relentless activism and moral fervour, reminds us that truth exists, even when it disappears from view. He reminds us that an apple can never be a banana.