11 Movies by Roman Polanski You Should Watch

Few film makers have experienced such interaction between their personal and artistic life as Roman Polanski. Profoundly marked by the nightmares of his childhood in the ghetto of Krakow, during which he witnessed the death of his mother, Polanski created a body of work intimately close to his life.

Polanski’s films obsessively explore the themes of insanity, horror and paranoia, possibly an attempt to exorcise his demons. But, beyond these fiery tones, there are profound and intelligent political messages in all Polanski’s work. Polanski never lost his freedom and identity, and never made a victim of himself, rather preferring to analyze the zeitgeist of his epoch with a keen and subtle eye.

Knife in the Water (1962)

Polanski’s feature debut, which was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, is a tense psychosexual thriller about two men competing for the same woman. After a bourgeois couple driving to a lake nearly knocks down a handsome hitchhiker, they bring him along for a day in their boat. The materialistic older man patronizes and goads the young stranger, a student, but it is the bikini-clad-wife who makes the decision that brings about a shift in the Darwinian social order. Brilliantly directed, the film put Polanski on the map. It may have influenced the work of Michael Haneke.

The Tenant (1976)

A disturbing movie about a dashing descent into the depths of personal hell. There is a touch of the suffocating, paranoid atmosphere of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, but here it is worse, much worse. The Tenant is a genuine nightmare in which Trelkovsky (played by Polanski), a shy and discreet man who works in an archive, is installed in an apartment in a particularly strange neighborhood. The indistinct, eerie sounds in the apartment, the feeling of being watched by laconic, inhuman neighbors, and the growing loneliness, anguish, and madness of the character gradually contaminate the viewer until the climax in the last, terrible scene. A nightmare and an abomination. And unforgettable hallucinatory screams.

Repulsion (1965)

Repulsion is considered by movie-goers as the first film of Polanski’s “Apartments Trilogy” (the others being The Tenant and Rosemary’s Baby) in which apartments became malignant conscious entities, playing an essential role in the alienation of several characters. In Repulsion, Carol, a young schizophrenic sex-phobic woman superbly interpreted by Catherine Deneuve, plunges into growing dementia that culminates in murder. The evolution of the events is absolutely terrifying, as we witness the worsening of Carol’s disgust for men which culminates in pure, hysterical, bloody madness.

Chinatown (1974)

Chinatown reproduces the aesthetics of the film noir genre in a sardonic reflection on the unglamorous, corrupt underworld of capitalist America and, at a deeper level, of human beings in general. The movie is based on Robert Towne’s script, whose depiction of the lacklustre feeling that underlines American capitalism impressed Polanski. But his genius goes beyond this, and delivers a film in which corruption is analyzed in all its forms. Jake Gittes, a private investigator who specializes in adultery receives a visit from the false Mrs. Mulwray, who asks him to find out if her husband, a water engineer, has had an affair. Mr Mulwray is soon found dead, but Gittes persists in his investigation despite death threats. The ending, a scene from a Greek tragedy, announces Polanski’s pessimism towards the viciousness society.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

A horror classic that became a sort of cursed movie due to the murder of Polanski’s pregnant wife Sharon Tate the year after its release. Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and Guy Woodhouse move into an apartment in an old Manhattan building that is quite disturbing due to the sinister reputation of past residents. The film delivers a succession of images that haunt us long after the screening in a perverse, subtle way. The greatest merit of this psychological drama is its ability to make us close to unspeakable abomination, to make palpable the anxiety of the heroine, and to introduce doubt and mystery through pungent dialogue, intrusive neighbors, disappearing objects and fear. This fear is of the neighbors and, even worse, of the baby Rosemary is carrying. This poisoning atmosphere contaminates the whole story and encourages Rosemary’s inevitable descent into madness. Polanski brilliantly manipulates the aesthetics and symbolism of the carnal and the religious: the haunting satanic past of the apartment and the image of the pregnant woman becomes the allegory of a repulsive nightmare, the result of a monstrous rape.

The Ghost Writer (2010)

Written, shot and edited just before the arrest of Polanski in 2009, this political thriller is based on the 2007 novel The Man Behind the Curtain by Robert Harris, who co-wrote this adaptation with Polanski. In the plot, a writer (Ewan McGregor) is chosen to finish the memoirs of a former prime minister (Pierce Brosnan) after the previous ghost writer died in strange circumstances. The result is a marvel of precision and balance: chiselled dialogue, permanent suspense, skilfully distilled humor, and an excellent ending.

Tess (1979)

Polanski adapted the Thomas Hardy novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles with virtuosity. In 19th century England, a Dorset peasant, John Durbeyfield, discovers by chance that he is the last descendant aristocratic family. Motivated by the profit he could make from this lost nobility, he sends his eldest daughter Tess to the wealthy family of the d’Urbervilles. The young Alec D’Urbervilles, charmed by the beauty of his cousin, attempts to seduce her. A pregnant Tess returns to her parents where she gives birth. The heroine then flees her village and finds work on a farm where nobody knows of her misfortune. There she meets true love in the arms of a pastor’s son. Tess, a manipulated, mute martyr, is the last of her kind, the embodiment of a lost innocent pastoral world betrayed by the greed of her own clan, a kind of Iphigenia sacrificed by her father Agamemnon for the favor of the gods.

The Pianist (2002)

The Pianist is based on the memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a famous Polish pianist who was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust. Wladyslaw (Adrien Brody) manages to avoid deportation, but finds himself still trapped in the Warsaw ghetto. One day, he manages to escape, and takes refuge in a ruined building where a German officer, moved by his music, helps him to stay alive. Polanski had long wanted to discuss the persecution of Jews in Poland during the Second World War, having himself been a victim of this: as a child he was forced to join the ghetto of Krakow. Although Polanski’s intention was not to create an autobiographic movie, he speaks of this painful period of his life through the memoires of Szpilman, as if the pianist was his alter-ego. Szpilman symbolizes a whole community and race stripped of dignity, humanity and, finally, of life.

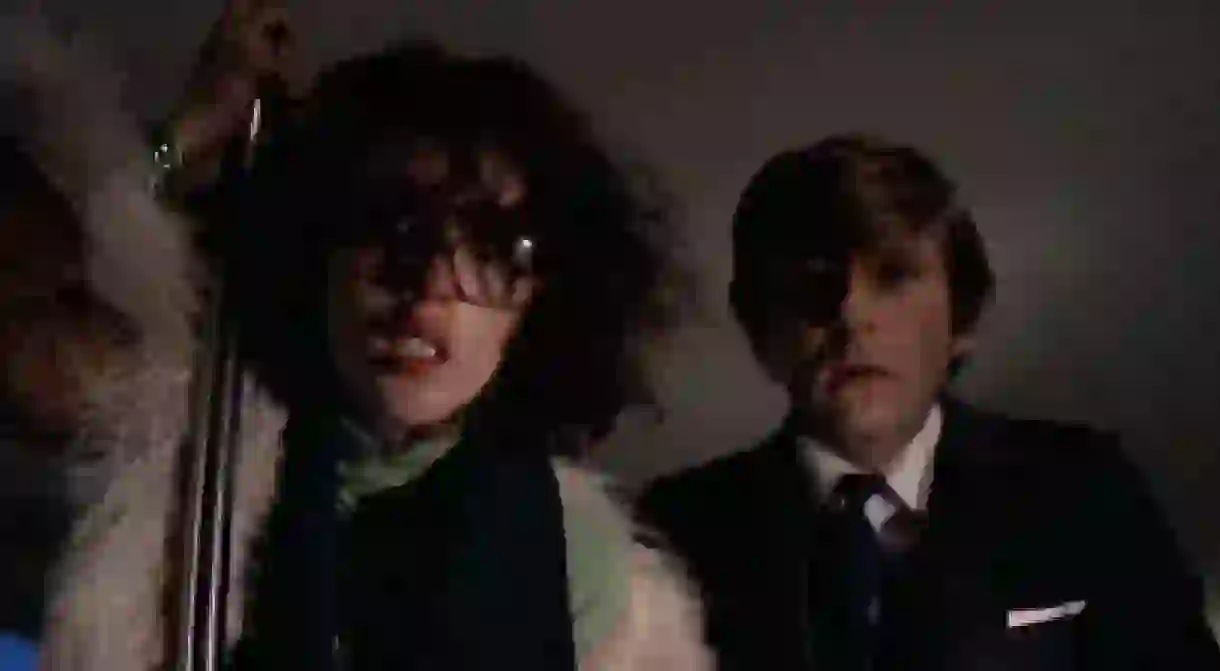

The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967)

The musical comedy Le Bal des Vampires, adapted from Polanski’s movie The Fearless Vampire Killers is currently playing at the Théâtre Mogador in Paris. It success is evidence of the vitality of the movie’s story. Professor Abronsius, a wacky scientist, dedicates his life to hunt vampires in Transylvania. One day, in the company of his faithful assistant Alfred, he arrives in a small inn full of garlic, which he suspects is a den for vampires. The terrorized villagers refuse to answer the questions. Despite all precautions, Abronsius fails to prevent the abduction of Sarah, the daughter of the innkeeper. The musical intensity is at its highest level, the pace is accelerated: the vampire is acting out. The inevitable sexual metaphor associated with the vampire bite is retained by Polanski, who inserts several suggestive scenes, as the ecstatic face of the young woman and the blood stain symbolizes the loss of virginity.

Frantic (1988)

Richard Walker, an American cardiologist, arrives in Paris with his wife Sondra to attend a medical conference. A few hours later Sondra mysteriously disappears, and Richard despairingly searches for her in a city he doesn’t know. Polanski reconstructs a different and scary Paris in this thriller co-written with Gerard Brach, and the pace of the movie triggers fear and anxiety in a style very similar to Hitchcock‘s, to whom he pays an implicit tribute. A shower, a corpse, a mysterious statuette are the elements of a puzzle that fit together in a frantic investigation, the key to which is a sensuous, unpredictable woman, Sondra. The icing on the cake is the couple’s dance scene to the sound of ‘I’ve Seen That Face Before’ by Grace Jones.

The Ninth Door (1999)

Corso, a researcher of rare books for wealthy collectors, receives a mission from an wealthy bibliophile: he has to find a satanic invocation manual entitled ‘The Nine Doors of the Kingdom of Shadows’, supposedly adapted from the book ‘Delomelanicon’ (The Book of Lucifer). Fuelled by a huge cheque and his own insatiable curiosity, Corso goes in search of the mysterious work, but he soon discovers the price of such a quest. Polanski again shows his immense ability to involve the viewer in unbearable suspense and anguish, telling the story of a man that, despite himself, is persecuted by the devil worshippers resembling those from Rosemary’s Baby, and, in doing so, is echoing himself.