Europe’s Heart is an Open-Air Museum: The Story of Europos Parkas

When artist Gintaras Karosas first presented his plan for an open-air sculpture park to the Lithuanian authorities in 1987, they found his idea ridiculous. Today, Europos Parkas is Central Europe’s most authentic and ambitious sculpture park, attracting artists, art enthusiasts and tourists from all over the world. Kotryna Džilavjan talks to Karosas, the founder of Europos Parkas, about the project’s difficult beginnings and its triumphant rebirth.

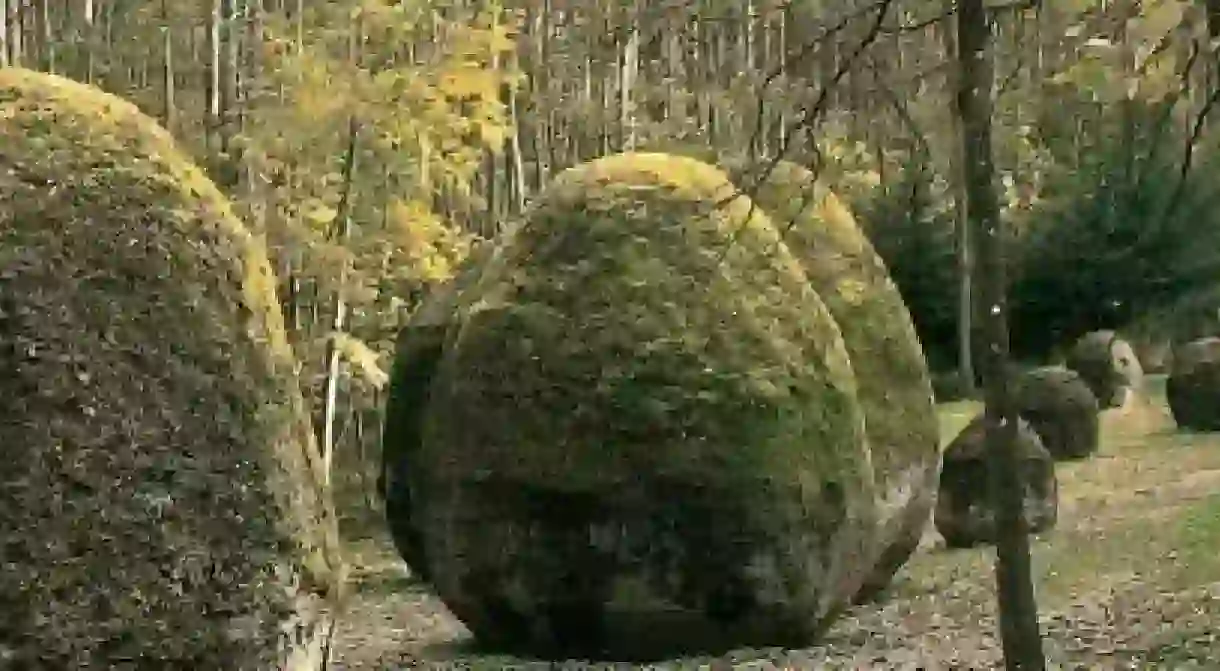

First it was the place itself. It looked like mythical places: hardly passable, mysterious and easy to get lost in, eternal in time and space, present everywhere and in the middle of nowhere. A shaded, waiting forest filled with a feeling of transition and awakening. Many old myths tell us about a hero travelling to a distant and strange land protected by wide-awake guards. A place is not only a setting for action; it is a living organism, a hero’s testing and goal. Its discovery requires physical strength, mind and will efforts or help from magical items: Hermes’ sandals, Ariadne’s thread or the sound of Orpheus’ harp. The place is not really welcoming but difficult to get out of too – it is the price you pay for its discovery.

This forest we describe is much younger than any of the archaic mythical locations but its pull is as strong as theirs. This story about its beginning has a principal character, a hero of today, a young over-achiever with the passionate idea and determination to realise it. He was looking for, found and entered the wood, its space pulling him in like a quagmire to cast a spell and keep him there forever. This was how a wonderful story began about nature and art, a man and the truth of his life, about a daily fight for long-lasting and precious values. It is a story about Europos Parkas.

Now, it is interesting to leaf through black-and-white photos – witnesses of the first steps that Europos Parkas took. Photos of the scrubs, squishy swamps, piles of dirt, deadwood bonfires and a single, stubborn man armed with an axe. A few years of deforestation, soil drainage and water collection had passed and a shabby wood found by Gintaras Karosas near Vilnius was resurrected for a new life as a public wood park.

With a new and clean shape the space acquired a new identity related to its geographical location. The place shifted: from the middle of nowhere it ended up in the middle of Europe. In 1989, Jean-George Affholder, a scientist at the French National Geographic Institute (Institut Géographique National), determined that the geographical centre of Europe was located in Lithuania. At that time this fact was little publicised, and was not yet used for the creation of the country’s Central European image.

According to Gintaras Karosas, the founder of Europos Parkas, ‘In 1987 when I decided to open a sculpture park out in the open, the calculations of the French geographers had not been published yet. However, I already knew that the centre of Europe was near Vilnius – this fact was mentioned in interwar textbooks. The real coordinates specified by the French in 2004 are 1.5 km away from Europos Parkas. This geographical idea seemed to me semantically important – a sculpture park in the middle of Europe. So, I started looking for a place near Vilnius with a good aura. I was avoiding urban background as it affected and upstaged the nature. It took a while – around a year – for me to find a place meeting these requirements.’

What was in the periphery ended up in the centre, and being in the centre turns a place into an important signpost. The newly found territory was settled: Europos Parkas started representing the idea of a centre. It identified itself with it; mentally and physically rooting the central point of Europe in a new, growing open-air sculpture museum. Now, it is not that important that the precise centre of Europe is a little bit further out or that such discoveries are hypothetic, based on changing geographical calculations. Later, the idea of a different centre – the heart of modern sculpture – started, and Europos Parkas gradually became the one.

Gintaras Karosas maintains that ‘Lithuania could neglect the idea of the centre of Europe. I believe that Europos Parkas and the spread of art in it helped to root this fact in people’s consciousness. The integration of such idea into a self-image and identity has never been only an empty declaration. It brought artists to Lithuania, where they lived and created… It is a living process, which has slowly created a certain value under the sign of Europos Parkas. The value survives and tells of the idea. Hence, one of consequences of our activity is the belief that we are at the centre, contributing to the formation of the European identity.’

The history of the best-known sculpture parks proves that it is easier to set up and maintain a park, to seek for reputation and state support when you have institutional impulse and protection. This model could not be applied to Europos Parkas at all, since from the very beginning the ideas of its founder Gintaras Karosas invoked resistance even in their own cultural environment. Karosas, then a student at Vilnius Academy of Arts, presented the idea of the first international sculpture symposium to the management of the Academy, however, it did not receive the proper support it needed. As he recalls, ‘When preparing for the symposium in Europos Parkas, I hoped to receive recommendations from the Academy so that it would be easier to look for sponsors. Let’s remember Lithuania’s position at that time, as a post-Soviet country, whose people were still overcome by stagnation. The management’s attitude was that a student should not invite foreign artists by himself as it was the prerogative of the Academy of Arts or the Artists’ Association. They urged to include classmates and organise the symposium at a local level. I was considered in the department and at the Senate of the Academy as a whippersnapper, who would bring huge shame to the independent Lithuania.’

It is no surprise that during the country’s political, economic and value transformation, the ideas of Gintaras Karosas seemed to be fantastic, suspicious and unreasonable. The distrust in his home country only weakened much later, long after the activity of Europos Parkas had been well under way. It was only in 2006 that Lithuania properly acknowledged the founder and landscape designer of Europos Parkas. Gintaras Karosas won the National Advancement Award for the establishment of the open-air museum and his talent in the education of Lithuania’s future generations.

He says, ‘The sculpture park has never been only about meeting my ambitions. The most important aspect of my activity has always been working for Lithuania. Nowadays, patriotism is a pretty worn-out, difficult-to-define and often-underrated concept. And still I believe that Europos Parkas is significant universally as well as socially. From 1920 to 1944 my grandfather Vladimiras, a surveyor, worked as a civil servant – a land manager at Utena County in Smetona’s Lithuania. On 16 February 1931, he was awarded with a Gediminas medal for merits to Lithuania by the President of the Republic. My grandmother descended from the nobles who had manors in Utena and Panevėžys Counties. She and her family were on a list for exiles, however, they moved to Germany and then to Canada in good time. My father, a teenager at that time, stayed in Lithuania and was exiled to Siberia. Being a juvenile, he was released in a year, but had a criminal record during the whole Soviet period. The trauma that marked history of my family is another reason why I want to be a part of Lithuania’s public life. Emigration, giving away your energy elsewhere seems so pointless to me. Tangibles are at the bottom of the pyramid of objectives, while at the top of it – not only self-realisation, but also the desire to contribute to the positive processes in the country.’

The development of the vision of Europos Parkas also needed a legal framework, administration and reputation. Any further development of the park was still completely dependent on Gintaras’ initiative and determination. The most successful foreign sculpture parks have been formed with the help of professionals, while Europos Parkas represents the artist-administrator model, all relying on the versatility of one man: Gintaras Karosas as the head of the establishment and the artist too, the creator of individual sculptures in the park and the designer of the landscape entity and park buildings. Looking at Gintaras’ work, you ask yourself where this absolute dedication for the sole life project comes from.

He has a ready answer: ‘Why a sculpture park? Why creating this setting in the nature? It comes from my childhood. I spent all my pre-school life in a farmstead at a hill and a forest. I felt that nature was full of authenticity, full of truth. I was very fond of drawing nature and forests: using a thin feather I would spend 50-60 hours on one drawing, indicating the number of the hours on the overleaf… It was like a confirmation for me that I did not flounce or waste my time for nothing. Even back then I was sure that I would be an artist, so those drawings make up a very important part of my past. My drawing technique was rather odd – I would start with the background and then move to the object. I was trying to connect with the nature using artistic means and to create landscapes – just that then it was only on a piece of paper.’

Europos Parkas, the idea first met with scepticism, eventually turned into a public institution, an organised structure that collects, upholds and exhibits works of art, develops educational activities – in short, performs the functions of a museum. Gintaras Karosas manages to bring to life highly ambitious ideas, such as cooperation with celebrities of modern art – Dennis Oppenheim, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Sol LeWitt, Beverly Pepper. Their works dedicated specially to Europos Parkas gave prestige to the museum, spotlighted it and formed the image of an elite sculpture park.

Having started his project in 1987, Gintaras Karosas has implemented it all by himself with only symbolic support from the state institutions. Thanks to him and his team, today Europos Parkas is one of the main cultural attractions in Lithuania. After fourteen years of its existence, the State of Lithuania had finally acknowledged Europos Parkas as an object of national significance. The space of Europos Parkas has always been open to various art practices – it has seen artists’ performances in the open air, performances of modern dance, special temporary exhibitions of sculptures. The most organic process in Europos Parkas, however, is its transformation, moving in the rhythm of a slow and unconditional dance. Old sculptures die, are reborn, meet new ones – and all of this happens in a natural sanctuary permeated with a special aura, in the periphery which has become the centre.

By Kotryna Džilavjan