The Highest Paid Athlete in History Was a Roman Charioteer

Thanks to multi-million-pound contracts, prize money, sponsorship and lucrative endorsement deals, the world of sport is flush with cash. Skilled – and savvy – athletes can command huge sums of money. Cristiano Ronaldo, for example, made $93 million in 2017, putting his total career earnings at $725 million. According to Forbes, the highest-paid athlete of all time is Michael Jordan, who is now worth a whopping $1.85 billion. Ask historian Peter T. Struck, however, and one ancient Roman chariot racer vastly surpassed this sum.

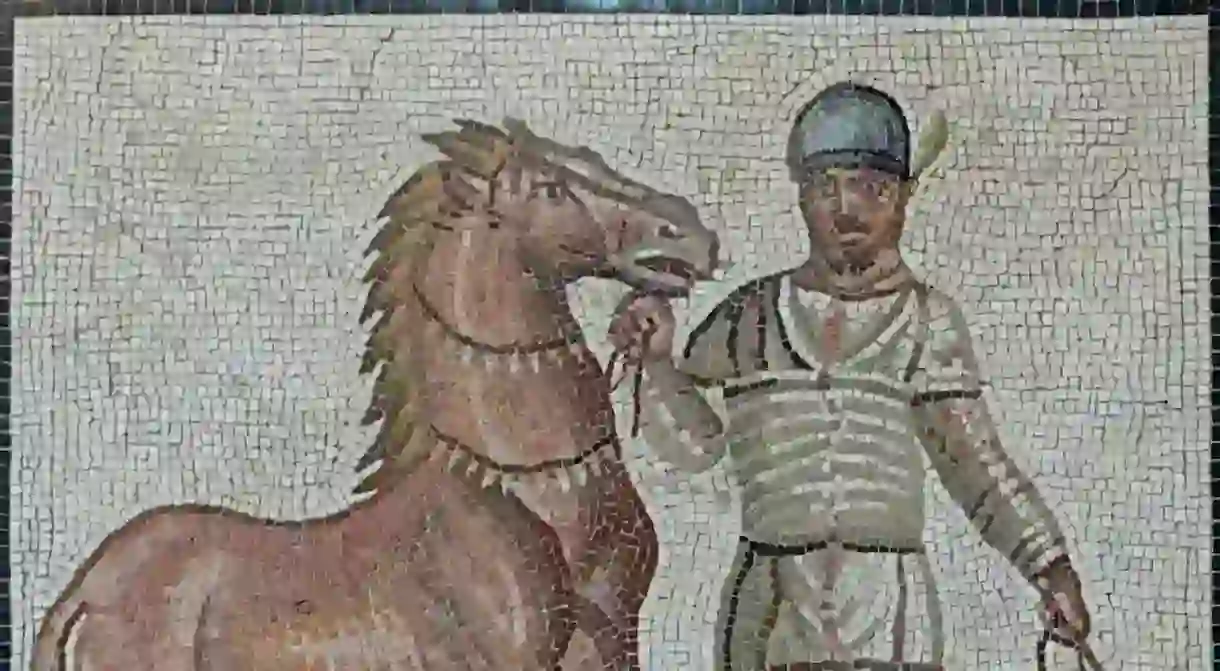

Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a Lusitanian Spaniard thought to have been born in 104 AD, amassed a fortune of 35,863,120 sesterces in his 24-year career. The exact figure is known thanks to a monumental inscription erected in Rome in 146 AD. Commemorating his retirement from the often-bloody sport of chariot racing, the inscription describes Diocles as the “champion of all charioteers”.

On retiring aged 42, Diocles had amassed a fortune worth five times what the highest-paid provincial governors at the time earned over a similar period. It was enough coin to provide grain for the entire city of Rome for a year or to bankroll the Roman army at its peak for a fifth of a year.

It’s this analogy that Struck, professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, used to calculate the modern-day equivalent of 35,863,120 sesterces. “By today’s standards that last figure, assuming the apt comparison is what it takes to pay the wages of the American armed forces for the same period, would cash out to about $15 billion,” Struck writes.

To earn that $15 billion, Diocles competed in 4,257 four-horse races, winning 1,462 of them. He also placed in another 1,438 races, mainly in second position. Other charioteers, however, recorded more victories – Flavius Scorpas won 2,042 races while Pompeius Musclosus racked up an impressive 3,559 wins.

Not just about the numbers, it was Diocles’ shrewdness in selecting when to compete that bolstered his financial success. Over a thousand of his victories were in single-entry contests that involved the best driver from one stable racing against the best driver from another stable. These races were prestigious and probably offered high prize money.

Some contests were likely seen as part-pageant or held a special significance that went beyond simply winning or losing. Certain races, for example, took place after street parades in which the charioteers formed part of the procession. Others, which Diocles seemingly avoided, involved two or three chariots of the same team pitted against chariots from a rival stable.

In other words, Diocles – not unlike many modern athletes – followed the money.