Milan and Modernity: Two Towers Tell the Story of a City in Flux

Italy’s Economic Miracle was the catalyst for a new era of design. In this post-war period of change, two towers were erected in Milan – one sought to connect the city’s illustrious past with its present, while the other reflected preoccupations with a prosperous future.

This story appears in the third edition of Culture Trip magazine: the Gender and Identity issue.

In 1958, Milan was booming. It was an era of buzzing Lambrettas, sharp tailoring and new money. The future beckoned, and it was as bright as espresso-machine chrome. The origins of the boom, dubbed the Italian Economic Miracle, lay in a trifecta of forces: US post-war investment, the formation of the European Economic Community and an influx of cheap labour fleeing the impoverished south. Milan, torn apart by Allied bombs in World War II, began rapidly reconstructing itself. A new city needed a new architecture and two contrasting visions emerged.

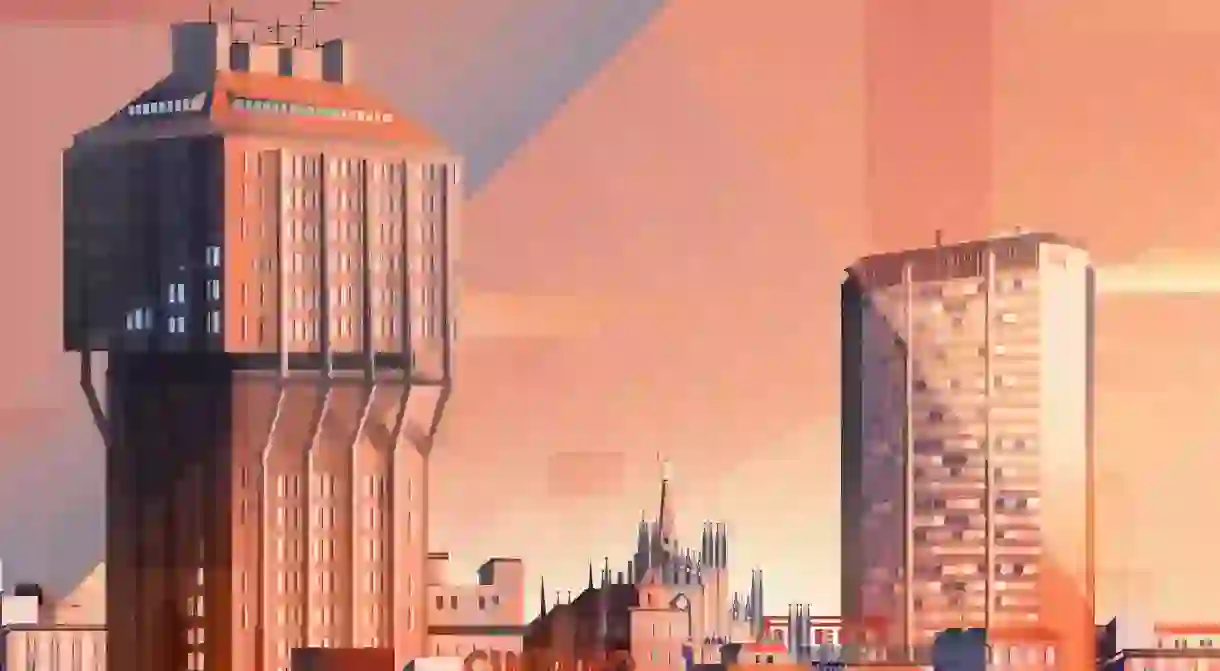

The best view of one of these visions is from the roof of the gargantuan Duomo de Milano (Milan Cathedral), the construction of which began over 600 years ago. If you can prise your eyes from the masonry, which is almost tyrannical in its detailing, you will notice a curious, top-heavy building looming over the surrounding rooftops: the Torre Velasca (Velasca Tower). Finished in 1958, it was the contrivance of BBPR, an erudite group of Milanese architects who believed that by mimicking history they could reconcile Modernism with Milan’s rich heritage. To span the ever-widening gap between old and new, the studio adorned the Velasca with an array of motifs – pilasters resembling the Duomo’s flying buttresses and a pitched copper roof redolent of Lombardy’s Medieval forts. By fabricating links to the past, the architects hoped the tower would slip seamlessly into the old city. In reality, these careful references had the opposite effect. Like the ageing prince in Lampedusa’s elegiac 1958 novel Il Gattopardo (The Leopard), the Velasca seemed ill at ease with the rapidly shifting social backdrop. Old certainties were being stripped away and, in its origins and its form, the tower revealed the tensions simmering beneath Milan’s shiny new facade.

BBPR was at the vanguard of an intensely creative period powered by consumerism. New wealth demanded new products and designers like Achille Castiglioni, Ettore Sottsass and Vico Magistretti were on hand to conjure them up. In 1961, a handful of these designers founded the Salone del Mobile – a furniture fair championing Italian taste and ingenuity. Milan’s newfound swagger was articulated in the elegant steel swoop of an Arco lamp and the refulgence of an Olivetti typewriter. Design and mass production drove the economy forward and against this canvas of plastic and aluminium, the Velasca’s dogged grip on the past looked increasingly out of step.

Its 1959 unveiling was mired in controversy. The British critic Reyner Banham was so incensed by this perceived bout of nostalgia that he kicked off an international row with an epic j’accuse titled ‘Neoliberty: The Italian Retreat From Modern Architecture’. Ernesto Rogers (the R in BBPR) fired back with an oblique response: ‘The Evolution of Architecture: Reply to the Custodian of Frigidaires’. Popular opinion sided with his antagonist.

Opposite the muscular Milano Centrale railway station, a more pertinent vision for Milan was shaping up in the blade-like form of Gio Ponti’s Grattacielo Pirelli (Pirelli Tower), finished in 1960. Like the Velasca, it was laden with symbolism, but of a less tangible nature. It was built on the site of the old Pirelli factory, bombed flat in 1943. Ponti’s response was a precisely engineered slice of international Modernism that paid little heed to the wider context. A dynamic convergence of architecture and advertising, it embodied the new Milan: bold and unapologetic. If the Velasca played the ageing prince, Ponti’s skyscraper was movie star Marcello Mastroianni in shades and a razor-sharp suit. And, like Mastroianni, the building photographed incredibly well, with an expressive face of glass and concrete that, in profile, appeared to melt into the sky. Obsessed, Italy’s greatest post-war photographer, Paolo Monti, captured it from every conceivable angle, even from a moving train. Monti photographed the Velasca, too, framing it as a hulking, ageless sentinel.

But not everyone was convinced. As Ponti’s skyscraper entered its final stages of construction, the Catholic Church suddenly took an interest in his work. Milan’s symbolic protector was the gold Madonnina (a statue of the Virgin Mary) perched on top of the Duomo, hitherto the highest point in the city. How could she keep watch while languishing in the shadows of Ponti’s tower? In response, a replica was hastily placed at the summit of the Pirelli. While pedantic, this gesture encapsulated wider misgivings over the direction in which Milan was headed. Polymath Pier Paolo Pasolini characterised the period as one of moral and intellectual decay augured by the Capitalism the Pirelli represented. For Pasolini, even sexual liberation had been reduced to a transaction, little more than “a necessary feature of the consumer’s way of life”. On film, Milan was represented either by the faithless bohemians of La Notte (1961) or the struggling southern factory workers in Rocco and His Brothers (1960). In 1969, striking workers picketed the Pirelli Tower.

The boom ended with a bang. On 12 December 1969, a bomb ripped through the Piazza Fontana, signalling the start of more than a decade of violence known as the Years of Lead. Milan weathered the turmoil, which was followed by a painful period of deindustrialisation. Corruption scandals engulfed the city in the 1990s. By the time Milan entered its next wave of prosperity in the mid-’00s, it had regained its lust for the new. Nowhere is this more evident than in the glittering glass towers sprouting up in Porta Nuova.

A Madonnina now resides in one of them – the development dwarfs both the Velasca and Pirelli – but the buildings she overlooks could belong in Dubai or Kuala Lumpur, or anywhere, frankly. Porta Nuova is the anonymous architecture of global capital for which Ponti’s building had in some ways prepped the ground. Now, as then, the Velasca Tower represents the road not travelled. Nevertheless, history has been kind to it. The building is revered as a uniquely Milanese response to the challenges of the modern world. BBPR never made another building like it, and Ponti’s career peaked with the Pirelli. And though the architects shared very different aspirations for their city, both buildings mark the moment when Milan leaped headlong into the future.

This story appears in the third edition of Culture Trip magazine: the Gender and Identity issue. It will launch on 4 July with distribution at Tube and train stations in London; it will also be made available in airports, hotels, cafés and cultural hubs in London and other major UK cities.