Sehr Gut | Very Good : Martin Kippenberger At The Hamburger Bahnhof

Kippenberger has been celebrated as one of the great German artists of the late 20th century. Lucy Watling writes about this fascinating artist, analysing some of his standout pieces of work that can be seen at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof Museum from 23 February to 18 August 2013.

Martin Kippenberger, Ohne Titel (aus der Serie Lieber Maler, male mir), Acryl auf Leinwand, 200 x 300 cm, Private Collection, 1981/© Estate Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Köln

Mired in history, wrestling with morality and populated by an imposing artistic elite; the landscape of late 20th century German art can seem a dark and mysterious place. Even within the art world many of these clichés still dominate. Only recently has curatorial attention begun to shift towards those who have worked to confound these stereotypes.

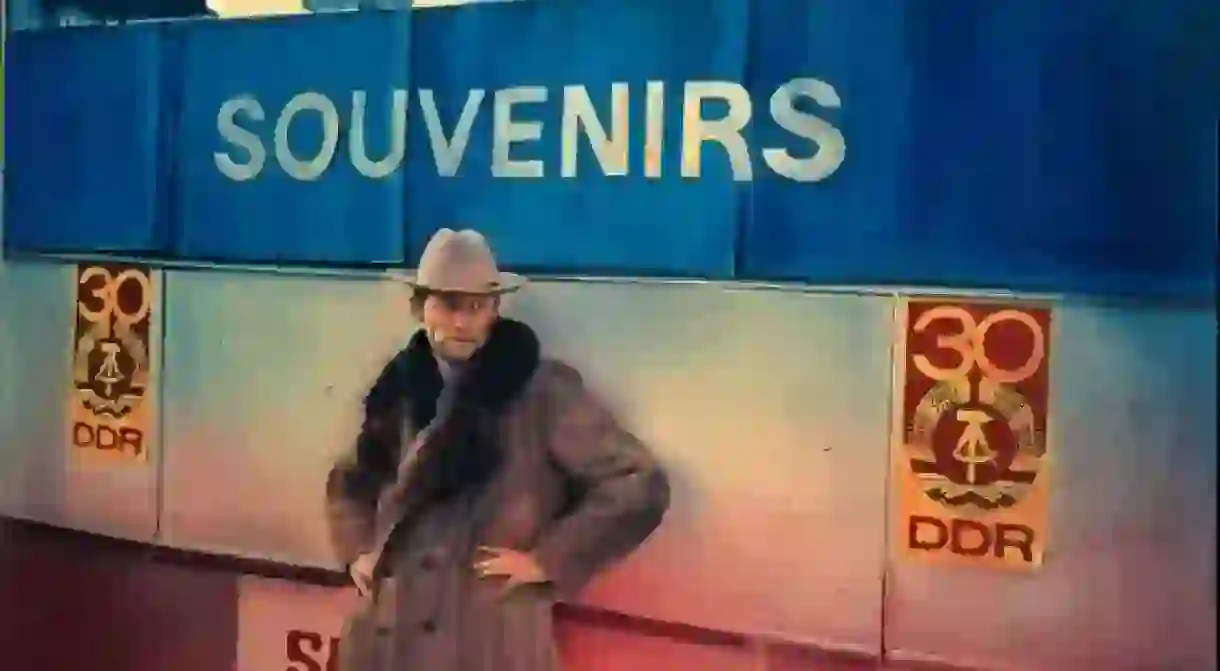

From 23 February to 18 August 2013, Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof Museum is running a retrospective exhibition of the works of Martin Kippenberger, a man described by the show’s curators as, ‘painter, writer, musician, actor, dancer, drinker, traveller, enfant terrible, self-stager and networker… in short, an exhibitionist’. Kippenberger was born in West Germany in 1953, and in the little over 20 years between his departure from art school and his death from cancer in 1997, he had made a career from systematically rejecting the norms of the German – and indeed European – art world. As evidenced by the works in this wide-ranging exhibition, Kippenberger was perpetually unfaithful to the traditional artistic media, working in painting and sculpture but also via graphic works, books, music and film. His works embraced humour, banality, uncertainty and failure – everything his industry had traditionally sought to exclude. He also happily became involved in all aspects of his presentation as an artist, not only producing the works, but often organising, curating and publicising his own exhibitions.

Yet during his lifetime, Kippenberger even rejected the idea of the retrospective, as his friend and collaborator Roberto Ohrt summarised, doing ‘everything he could to divert, confuse, and make it difficult to decode his work’. Does this mean visitors have little to gain from an exhibition such as this? The answer is a resounding no. Walking the rooms of the Hamburger Bahnhof, it is immediately clear that attempts have been made to rethink the traditional structure of the retrospective in a manner more fitting to Kippenberger’s style. Rather than presenting the visitor with a logical progression – from birth, via success, to death – visitors are left to draw their own conclusion about the artist’s life from the works on show, a refreshing approach to the idea of a career overview.

An example of how this method of curation works is the number of pieces that reference Kippenberger’s lifelong struggle with alcohol, though of course with none of the seriousness one might expect from such subject matter. With the large-scale oil The Torture of Alcohol (1981-2), the artist’s self portrait shows his mock horror at finding his hands bound by the plastic rings of a beer six pack, the final can still dangling between his wrists. In another room the importance of the artist’s international travels are emphasised, culminating in the 56 oil paintings of One of you, a German in Florence (1976-7). Throughout all of these themed segments, visitors can trace the extent and importance of Kippenberger’s self-constructed networks. This can be seen in his artistic or musical collaborations, and in the fruits of his various understandings with bars and hotels across Europe, under which he would provide works in exchange for free board and lodging.

Thanks to the presentation of Kippenberger’s network, this exhibition should be of interest to anyone seeking to discover more about both the West German cultural scene of the 1970s and 80s, and the climate immediately post-reunification. From the punk bands of Berlin’s Kreuzberg district to the artistic circles of Cologne, the works presented here give the viewer an insight into a period of creativity perhaps still largely unknown to an English-speaking audience.

Most striking to a visitor, however, will be the sheer variety of Kippenberger’s work, in both its medium and its style. In this respect the artist provides a fascinating example of how practitioners approaching the end of the century struggled to come to terms with the crumbling modernist traditions of the past. When Kippenberger compares himself to Picasso in works such as Untitled (1988) – featuring white oversized underpants that reference a 1962 photograph of the Spaniard taken by American photographer David Douglas Duncan – the comparison is, both physically and artistically, entirely unflattering. Positioning himself as a ‘jack of all trades’ Kippenberger intentionally becomes the master of none, forcing the visitor to question how art is, and should be, valued.

Quoted on a gallery wall towards the end of the exhibition, Kippenberger was typically dismissive of what he hoped to achieve with his life’s work:

What people will or won’t still be saying about me is what counts. Whether I have disseminated a good mood or not. And I’m working on people being able to say: ‘Kippenberger was good mood!’

With its crucified toy frogs, distorted street lamps and ‘Berlin Wall-paper’, it’s difficult not to leave this exhibition in a better mood than when you arrived. However, by skilfully treading the line between informative and provocative, the curators at the Hamburger Bahnhof have made clear that Kippenberger’s career was far more than simply a two-decade joke.

By Lucy Watling