Photographer Frank Thiel On Today’s Berlin: ‘No Boundaries Between People’

Photographer Frank Thiel has made a career out of keeping his lens fixed on the constant transformation of Berlin, a city still dealing with the trauma of being cleaved in two. Much has changed, much has been lost, and much has been created, but the German capital still marches to its own beat, led by some of the world’s most forward-thinking creatives.

A castle is being reconstructed right in the centre of Berlin. The Humboldt Forum at Schloßplatz will combine two of the city’s biggest museum collections and will open in phases over the next two years. The first version of the Berlin Palace (Stadtschloss) came down in 1950, demolished by the German Democratic Republic to make room for its parliament building, the Palast der Republik, which then suffered a similar fate in 2008.

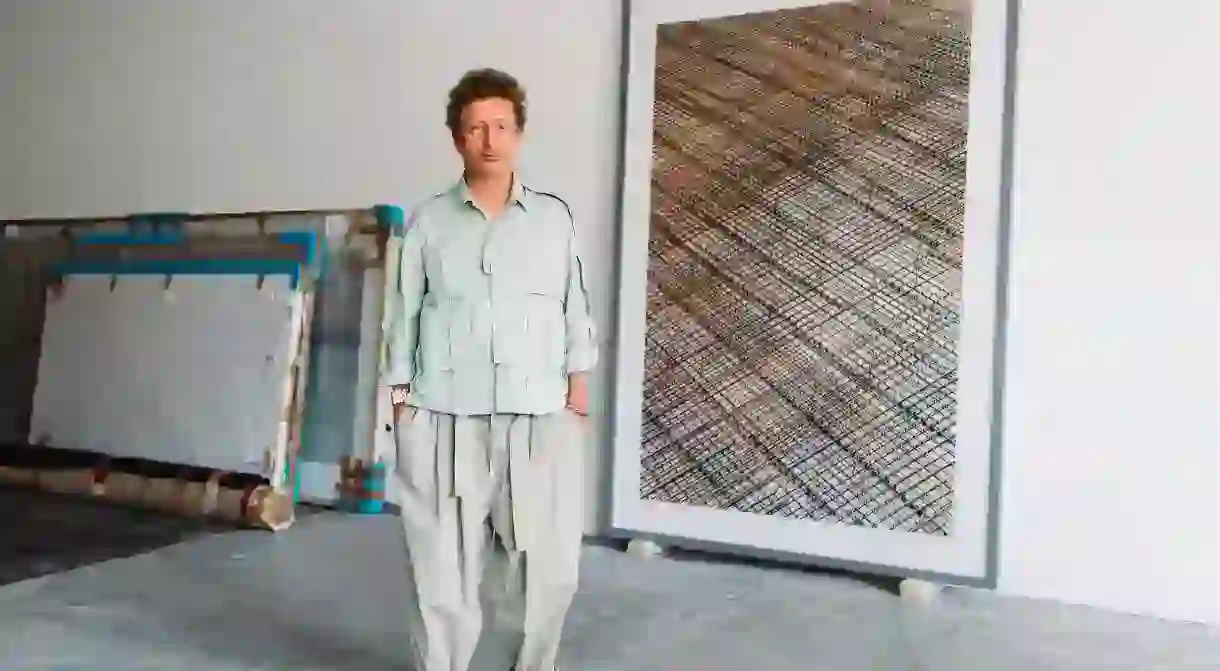

The current architectural development is of particular interest to artist Frank Thiel, who photographed the Palast der Republik just before demolition began, in 2003, as part of a series of untitled works about the changing architecture of Berlin after the Wall fell.

These images often single out the endless interlocking triangles of a building’s rafters, or the vast floors of a desolate building, producing a moment of tense stillness. “I always favoured the interim status over the end results in my practice,” says Thiel.

The Wall split the city’s residents from 1961 to 1989, and the past 30 years have been marked by attempts to heal the division it created. Thiel himself grew up in East Germany but went to West Berlin to study photography at age 19 and never left. “Honestly, before the Wall came down, I was finished with Berlin,” he says. “But then, I thought it might be an interesting time to give the city another chance.”

Indeed, since then, many parts of the city, such as Hackescher Markt in Mitte, where Thiel has lived for many years, have changed beyond recognition. Largely abandoned while the Wall was up, it became a hub of squats, colourful characters and pounding nightlife in the ’90s. These days, it’s much more sanitised. Thiel explains that his building was one of the first in the area to be renovated. What keeps him in the neighbourhood today is its ever-changing faces. “It reflects my personality, my curiosity, which is the fuel for everything I do,” he says.

Eventually, he ended up contributing to the changing fabric of Berlin with his light-box installation, Untitled (1998), which stands at Checkpoint Charlie, almost exactly on the spot where the Wall divided the city between the Soviet and American sectors. The work consists of two light-box photographs, one of an American soldier, the other of a Russian soldier, metaphorically representing the border, to remind visitors that what is now a freely accessible road was once two dead ends.

While in the tranquil setting of the Tiergarten, the city’s largest park, subversive artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset have installed a concrete stele that displays a different homosexual couple kissing every two years, in honour of those in the queer community who were murdered in the Holocaust.

Memorials like this are all around Berlin, markers of the city’s cataclysmic past. Some, such as the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, near the Brandenburg Gate, are obvious to even a casual visitor to the city. Others, such as Richard Serra’s Berlin Junction (1987), which stands in front of the distinctive yellow architecture of the Berliner Philharmonie, are barely noticed. Serra, a renowned minimalist artist who was also involved in the design of the main Holocaust memorial, honours the victims of the Nazis’ T4 programme, in which people with physical and mental illnesses were systematically put to death through “involuntary euthanasia”.

However, some of the most interesting work is happening at small, privately run project spaces. “This is a true treasure of the city, that you can discover a lot of young talent at a very early stage,” says Thiel.

Several newer spots are clustered in the northern, traditionally Turkish neighbourhood of Wedding, such as gr_und, uqbar and SAVVY Contemporary. South of the centre, one-off shows can also be found at Ashley in Kreuzberg and Horse & Pony in the backstreets of the rapidly gentrifying Neukölln, near the disused airport of Tempelhof, where young families fly kites and rollerblade. “I think the importance of Berlin is more as a place of artistic production and discourse, with no boundaries between people,” Thiel says.

This risk-taking, upstart attitude is what keeps artists flocking to Berlin, and Thiel couldn’t be happier about it, although he does note the changing ways people socialise today. “There used to be places you could go to and you just knew your friends would be there. That doesn’t exist to me now. There are too many places, not like Berlin in the ’90s.”

He namechecks legendary clubs that fell victim to the changing face of Berlin, including E-Werk, WMF and Planet. Yet some still roll on. Tresor, for example, was originally founded in 1991 on Leipzigerstraße, and reopened as a vast, and still popular, techno wonderland in a huge old power plant on Köpenicker Straße. Change, though, for Thiel at least, is what makes Berlin exciting. “Transformation – it’s the most natural thing in the urban environment,” he says.

This article is part of Culture Trip’s Art in the City series, which explores cities through the eyes of the artists who live and create in them.