France And The United States: History’s Ultimate Frenemies?

If all the world’s a high school cafeteria and all the states and territories in it merely bitchy teenagers then The Plastics, the traditional ruling trio, are the United States, France, and Great Britain. America, the ultimate queen bee, claims a special relationship with both her European allies; she shares a language with one and a symbol of common values, the Statue of Liberty, with the other. But like all cliques, these friends have history.

Most people pinpoint 1778 and the signing of the Treaty of Alliance as the start of France and America’s friendship. As is often the case, the groundwork was actually laid much earlier. In 1763, France lost to Britain in the French and Indian War and had no choice but to sign over Canada with the Treaty of Paris. Fast forward 15 years to the American War of Independence and the French were glad to embarrass their European rival by providing decisive support.

The revolutionary camaraderie ended abruptly in 1795 when the U.S. and Britain signed the Jay Treaty, resolving some hangover disputes and ensuring a decade of peaceful trading. This perceived betrayal led France’s Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand to refuse a U.S. diplomatic delegation in 1797. This affront, coupled with attacks on American vessels by French privateers, led to the two-year Quasi-War.

In 1803, France’s soon-to-be-emperor Napoleon Bonaparte found himself strapped for cash due to his war with the British and so decided to sell the entire French-controlled North American Territory to Thomas Jefferson for $15 million. The Louisiana Purchase (of around an 827,000 square-mile tract of land from the Mississippi to the Rockies) doubled the size of the U.S.

With the fall of the Second Empire in 1870, France decided to reaffirm its commitment to its old republican ally and their shared ideals. It did so with a gift: the Statue of Liberty, dedicated in October 1886.

America’s 1917 intervention in the First World War broke a three-year deadlock and led to an Allied Victory. However, tensions arose between Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Georges Clemenceau over the latter’s insistence on substantial reparations and territorial concessions from Germany, codified in the Treaty of Versailles but never ratified by the U.S. Senate.

In 1942, the Vichy government severed diplomatic relations with the United States. Two years later, General Charles de Gaulle led the first troops into liberated Paris. Despite normalization of diplomatic relations, de Gaulle’s Provisional Government was only reluctantly accepted by President Roosevelt. The effects of this were felt during the 1960s when de Gaulle protested America’s strong role in NATO and its special relationship with the U.K. He was determined to ensure an independent nuclear deterrent and negotiating position. Things came to a head in 1966 when France withdrew from the organization’s integrated military command structure and ordered U.S. forces off its soil.

Twenty-five years later, France and the U.S. found themselves in an unlikely honeymoon period. Surprisingly, President François Mitterand offered no opposition to the stationing of U.S. nuclear and cruise missiles in Europe to counteract those of the Soviets.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, France stood in solidarity with the U.S. Le Monde’s headline ‘Nous sommes tous américains’ captured the national sentiment and the government sanctioned military support in Afghanistan. In 2002, 62 per cent of French people viewed the U.S. favorably, but within a year relations had hit an all-time low when France threatened to veto the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In the U.S., anti-French sentiment was strong, ranging from the ridiculous (renaming French fries ‘Freedom fries’ in the Capitol Building’s cafeteria) to the serious (the barring of French construction firms from postwar contracts). In France, public opinion of the U.S. stayed below 50 per cent between 2003 and 2008.

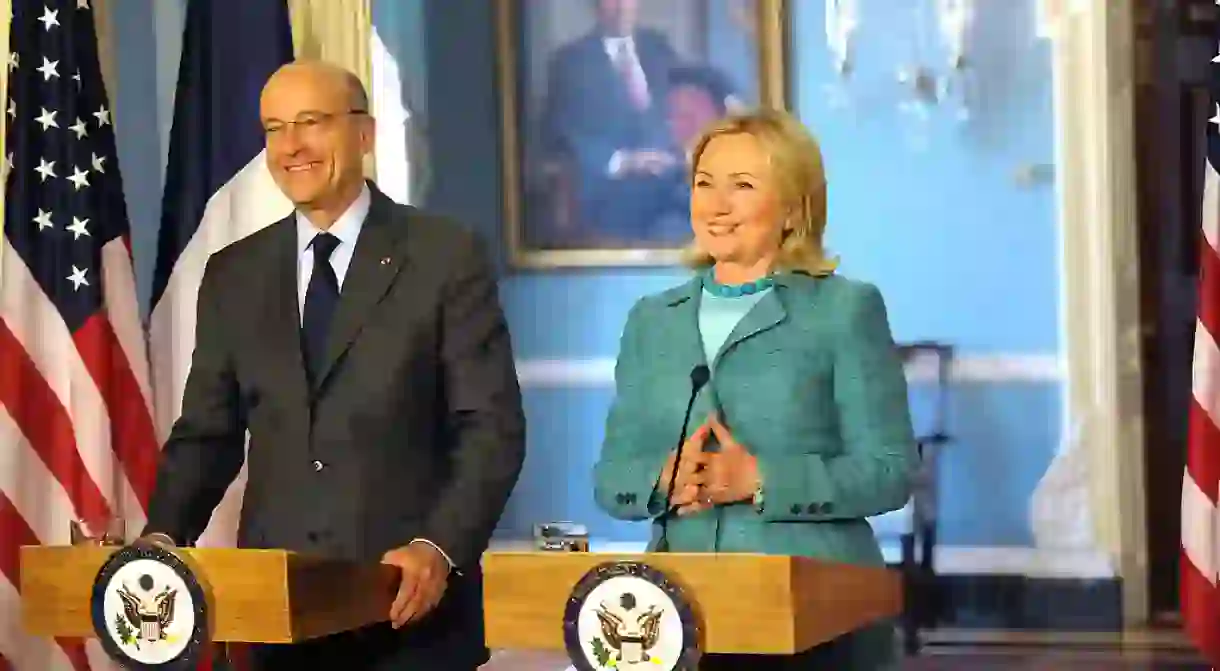

A rapprochement coincided with Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency in 2007 and warm feelings have continued under Presidents Barack Obama and François Hollande. In 2014, three-quarters of French people held a favorable opinion of the U.S., and in 2015 this was reciprocated by 85 per cent of Americans.

Whether this love continues or things take a nasty turn depends to an extent on the outcome of Tuesday’s election. A recent study found that 86 per cent of French people want Hillary Clinton to win as opposed to just 11 per cent who favor Donald Trump. This pro-Hillary stance was reinforced by France’s Prime Minister Manuel Valls who said that ‘Trump is rejected by the world’.

Whichever way Americans vote, 84 per cent of French people think their decision is important for the future of the world and 63 per cent believe so for France’s future specifically. It is feared that a Trump win could foment support for Marine Le Pen and the right-wing National Front.

So the United States and France may be BFFs, but that doesn’t mean they don’t sometimes distrust, hate, and even fear each other. And why should their friendship be any different from our own?