Gustave Moreau: Reimagining Symbolism

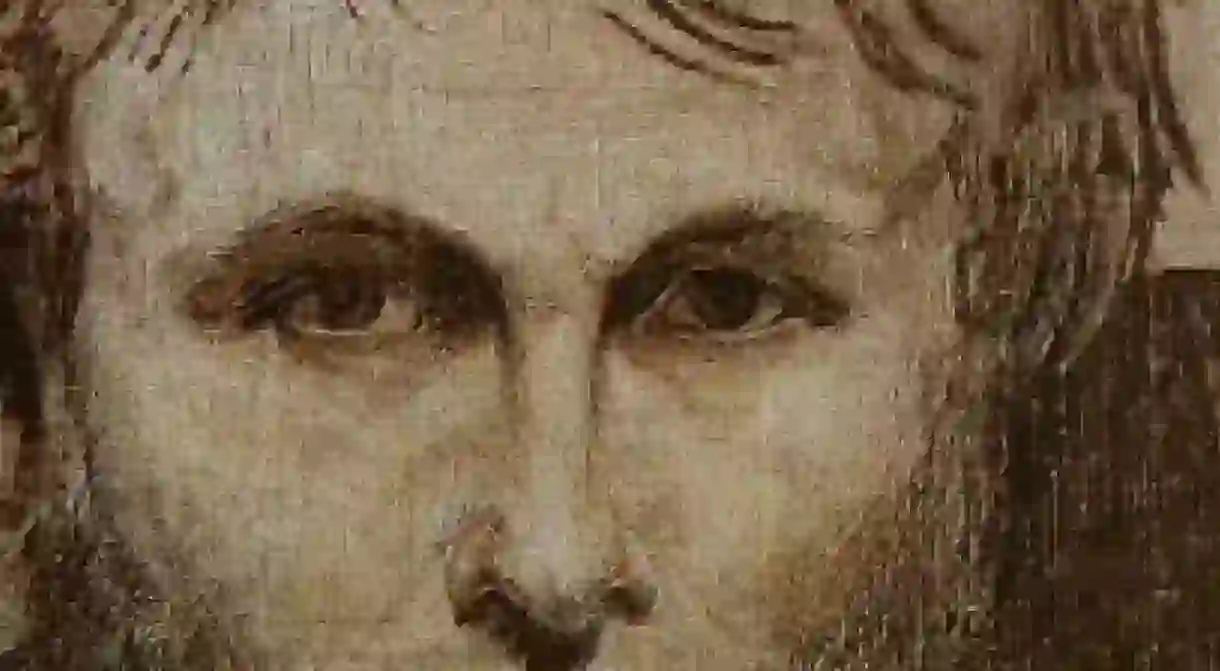

French Artist Gustave Moreau was one of the most vital artists of the 19th century and a leading light of the Symbolist movement. His works channelled both Renaissance art and the iconography of the Old Testament in an attempt to delve into the depths of his own emotions.

Gustave Moreau is known to be a French symbolist artist, but this definition is hardly conclusive. The confusion lies within the notion of symbolism itself. Since it unites so many literary and artistic currents, the illusion of uniformity is created. However, the movement is actually full of contradictions, allowing the different artists to explore and apply their individual tastes and predilections. Eccentricity and provocation are two defining characteristics of symbolist artists, all of whom created their own artificial world, built on their own imagination and emotions. Rejecting naturalism and impressionism, at the same time the artists challenged themselves to stimulate and evoke the observer’s emotions. Longing for sensation and artfully hidden implications, it seems only logical that every artist brings his unique touch to a common concept.

Moreau studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1846 to 1849, he had high hopes to win the Prix de Rome and he was named professor at the age of sixty-two. Like the vast majority of artists at the time, he exhibited at the Salon official, hoping for buyers, medals and fame. Stylistically speaking, Moreau is a neoclassical painter, although art historians see the first signs of abstraction in his late paintings. His Beaux-Arts education and a first visit to Italy as an adolescent left the artist with a deep admiration for the Renaissance. He returned to the beloved country for more than a year in 1857, spending his time contemplating and copying the Old Renaissance Masters like Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. The influence is clearly recognizable in Moreau’s use of the Chiaroscuro, the representation of the human body in all its perfection, the characteristic backgrounds and of course the complex compositions.

However, it is not only Moreau’s choice of means that channels the Renaissance. He focuses on the interpretation of biblical, mythological and pagan themes, but brings new light to a popular and frequently illustrated iconography. The painter invents side stories and rejects distinguishing characteristics. He created his own imaginary Oriental decorum, which was certainly fictional due to the fact that the artist had never been to the Middle East. His primary inspiration was the Old Testament, a source that recalls ‘a tyrannical and cruel use of power.’ Moreau’s masterpiece The Apparition from 1876 represents Salomé, the incarnation of the femme fatale, a recurring motif in Moreau’s paintings. According to the Gospels, Salomé was rewarded with the head of John the Baptist for dancing for Herod Antipas, the husband of her mother Herodias. Bloodthirsty and carnal, but at the same time pure and fairylike, Salomé radiates with mystic. Colours, ornaments, architecture and light ally to give a new aesthetic to a traditional iconography. Moreau does not aim for the viewer’s comprehension, but he wants to stimulate his emotions. A comparison of Moreau’s painting with Caravaggio’s version from 1607 makes this more than clear.

In 1852 Moreau’s parents bought a villa at 14, Rue de La Rochefoucauld in Paris, where the artist lived and worked until his death in 1898. Moreau decided to transform the entire house into a museum, a decision that inspired the artist to alter, rearrange and improve the four-story house during the last two years of his life. Without any living relatives, he left the villa, with its furniture, personal belongings and numerous paintings to the state of France. The Musée Gustave Moreau was inaugurated in 1903. The house, and in particular the artist’s studio, leave the visitor stunned and deeply moved by the colours, the arrangements and the great attention to detail. Like his monumental paintings, the rooms are built on a complex thought-out composition, which helps understand Moreau’s life and above all feel his art.