A Tribute To Congolese Literature: Writers Of The Congo River

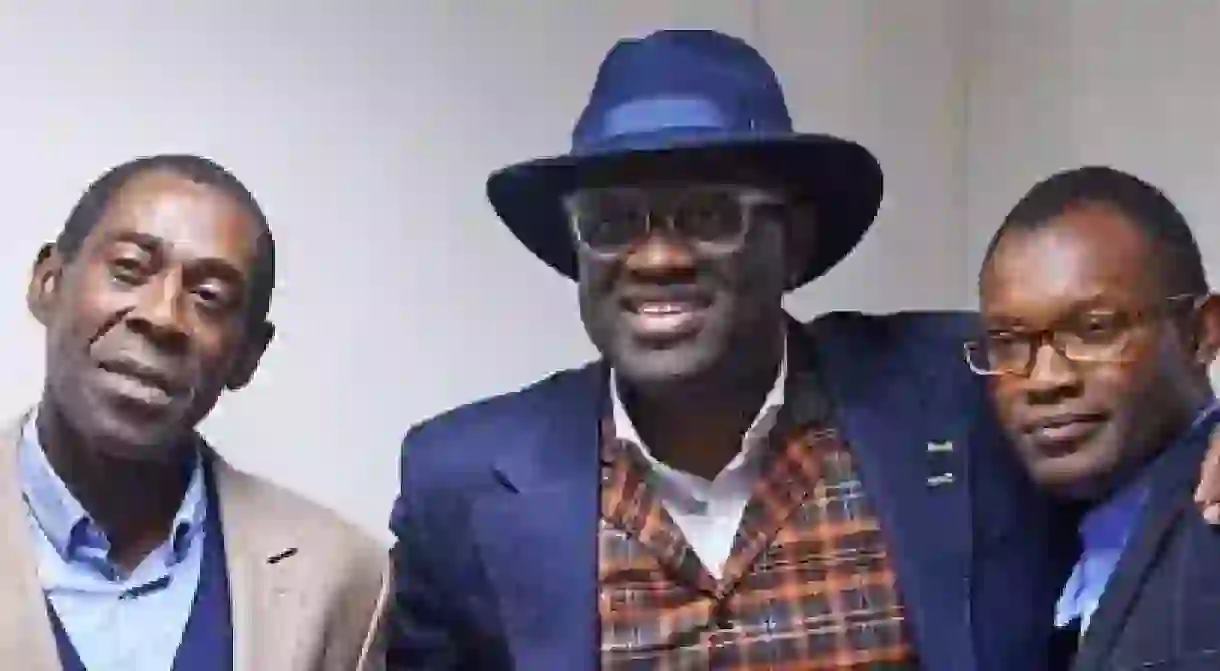

Meet three of the most talented African writers alive. In its artistic events venue, Bozar, the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels hosted a conversation between In Koli Jean Bofane, Alain Mabanckou, and Fiston Mwanza Mujila. It was a very lively literary event, within the ‘Bozar Connects: Africa’ program – dedicated to promoting modern African creativity and raising awareness of the African diaspora.

It was a rainy October night, and the room was filled with people from all kinds of ages, backgrounds and ethnicities. They had come to see three acclaimed writers of the African continent. The authors were gathered at this event, in a tribute to Sony Labou Tansi (5 July 1947 – 14 June 1995), one of the most important African writers of his generation. His novel, Life and a Half, was listed as one of the 100 best books on Africa of all time. He died tragically of AIDS at the age of 47. But his legacy continues, and these authors are the living proof of that.

In Koli Jean Bofane, Alain Mabanckou, and Fiston Mwanza Mujila represent the cultural heritage of the two countries who are divided by the immense Congo River: the larger, Democratic Republic of Congo, to the southeast (formerly known as Zaire), and the smaller, Republic of the Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville), to the Northwest. The river is the second-largest in the world in volume – after the Amazon – and represents a force of nature that brings life to its people. This is true both literally and metaphorically speaking.

‘Although there is a river separating us,’ says A. Mabanckou, ‘we both share the same culture, the same roots. The presence of the river shows itself in our literature, and it is what keeps it together, what solidifies it. If we look at certain other African works, originated from arid climates, we can sense that they are grainy, that they lack consistency, and that is because they don’t have the water to keep it together.’ The atmosphere is one of laugher and relaxation, not what you would expect from a typical ‘intellectual’ event at all, which makes it even more pleasant. Not only does the audience get to know major literary figures, but there is also the feeling of companionship, as if the writers were just chatting over a beer, while sharing some of their views and experiences.

The Congo river is one of the major points of economic trade of Central Africa: through it people transport cotton, palm oil, coffee, sugar and copper. It also powers two hydroelectric plants, and of course, gives life to the rainforest, containing the numerous animal species and flora that feed the population. Paradoxically, the river is also a symbol of defeat, as A. Mabanckou points out: it was through here that the Congo-DRC was explored and further annexed as a colony of Belgium. It was also through the mouth of the river that European colonization began in Congo-Brazaville in the late 19th century. But it is in the beginning of the country’s long-term affinity with Communism (namely through Russia, Cuba and China) that his new book takes place.

We are talking about Petit Piment, the latest of the already immense collection of works by A. Mabanckou, and the book that he has come here to promote. Born in Congo-Brazaville and now a French citizen, he is celebrated as one of the best living writers of the French language. He has also won a respectable range of awards, and was a finalist of the Man Booker International Prize in 2015.

Petit Piment tells the story of Tokumisa Nzambe po Mose yaomyindo abotami namboka ya Bakoko (meaning, in Lingala, ‘Let us give grace to God, the black Moses is born in the land of the ancestors’); but as it is too long to be pronounced, everyone just calls him Moses. He lives in an orphanage situated in the region of Loango, previously ran according to catholic principles. In the time when the book is set, the region has recently changed to fit the ideals of the Socialist revolution.

The imaginary of the child is filled with legends, which are entertained by the teachers and other locals, who act as props to the land’s history and culture. Of course, the tension towards the colonizing enemy is ever-present, and seems to function at times – in this same imaginary – as a type of collective scapegoat. The orphanage feels to him as a little world outside the real country; and the capital, Pointe Noire, like some sort of prophetic dream. So he ends up fleeing the institution and is hosted by a famous prostitute.

In a simple style that has the effect of reflecting the child’s internal speech, Moses is characterized as both a naïve and courageous character. The goal, says the author, was to see how he would react in the world of prostitutes, who happen to be very respected members of the society for their roles as confidents and comforters. But also to solve the question of hatred between the two types of Congolese, from each side of the river. It is, he continues to say, a matter that bothers him: sometimes, the questions of racism and exclusion come from the people within the same community.

Another book presented in this event was Congo Inc., by In Koli Jean Bofane, and the best way to introduce it would maybe be by its opening quote: ‘The new state of Congo is destined to be one of the most important executors of the work that we intend to accomplish.’ This phrase was proffered during the closing of the Berlin Conference, during which some of the most powerful European countries divided the African continent, in order to proceed to its exploitation and impede any form of autonomy. It was said by Otto von Bismarck, the conservative Prussian statesman who created the German Empire and controlled European affairs from the 1860s until the 1890s. And the long title of this book is indeed: Congo Inc. – The Testament of Bismarck.

It talks about the life of Isookanga, a half-pygmy who lives in a small village of the equatorial forest, and whose dream is to go to Kinshasa to make business. As an advocate of globalization, he believed that the forests should be destroyed in order to let the progress in. The style of this book is more elaborate: with detailed descriptions, the author finds a way of transporting us into the context, also filling the text with local expressions. Different perspectives corresponding to the characters allow us to interpret some of the ways of living in this sometimes puzzling country.

‘Congo is not a country, but a company’ – says In Koli Jean Bofane, explaining the main title of the book. And indeed, it seems like Europe has managed to organize and structure it in order to extract and profit from its immense natural resources: copper, gold, diamonds, cobalt, uranium, coltan and oil, just to name a few.

The last author to speak was a representative of the new generation, Fiston Mwanza Mujila. Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1981, this young author is a great promise for the future. He is also a poet and a theater writer. His novel, Tram 83, has been very well received by international critics. In it, two characters wander around in what seems like a hopeless urban dance, created by a cacophonous prose, cut dialogues, and a bitter tone. It progresses, frenetic, with an orgasmic rhythm. There are countless characters who dance at this pace, stomping their feet against the dusty floor, crying, complaining, tearing themselves and each other apart. There is sexuality everywhere. Mujila’s prose is so rich in color and sound, that is has been compared to authors as disparate as the Beatniks, Flannery O’Connor and Scott Fitzgerald.

All three authors were asked to read a passage of the book they were coming to promote, and Mujila’s reading, although he appeared to be the most shy, was the most lively: his voice sounded high as he incarnated the characters and narrative. All of a sudden, it was as if the novel’s population and surroundings had jumped into the auditory.

In this rainy October evening, the city of Brussels had the chance to see a glimpse of two African countries, and their literary talent.