Read Dominican Writer Frank Báez's Short Story "Karate Kid"

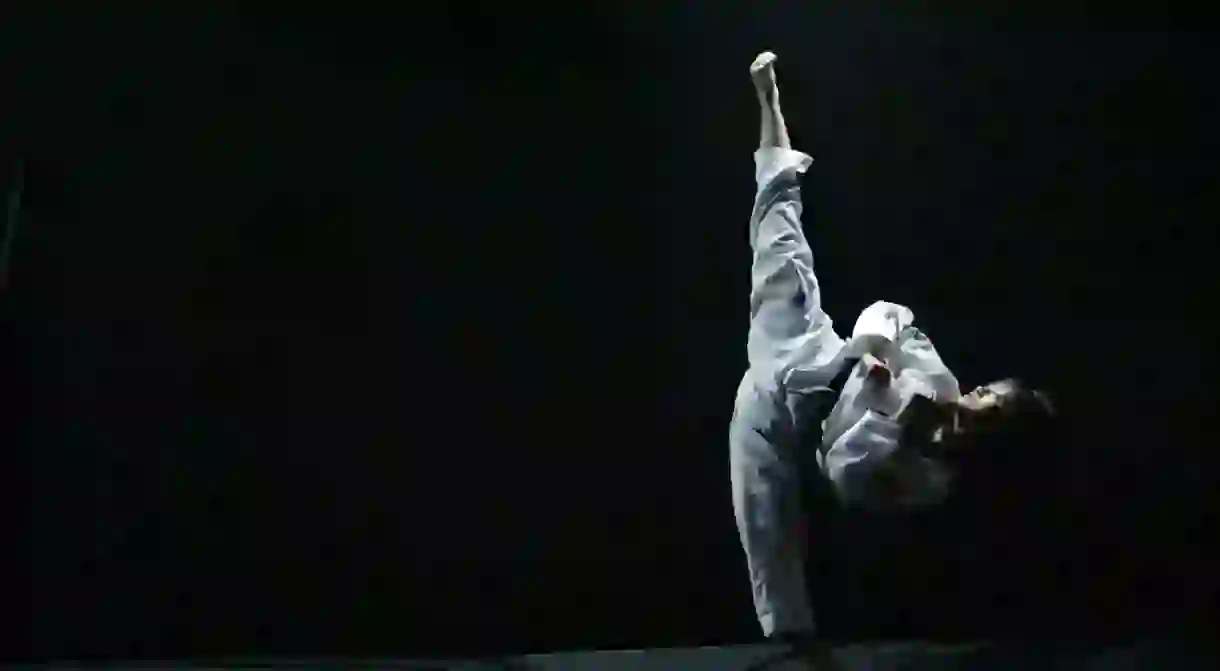

A big sister and a bully square off in the Dominican Republic selection from our Global Anthology.

I think I was the only one of my generation who hated The Karate Kid. Contrary to my friends who had the film recorded on VHS and watched it obsessively, I only saw it twice. The first time left me in anguish. The reason was that Ralph Macchio’s character looked like Carlitos, the neighbor bully, and the dojo scenes reminded me of my own attempts at karate. My dad had dragged my sister and me into taking karate classes during the martial arts boom that followed after the film was released in Santo Domingo. No joke. An academy opened in Miramar only a week after Teleantillas began broadcasting The Karate Kid. It had everyone talking. Those who had been bullied saw themselves in Daniel LaRusso, the protagonist. But so did the bullies, which was absurd. Likewise, it was strange that the victims wanted to learn karate in an academy, when the movie showed that it was the tormentors who actually trained there. So every time a new kid entered the class, I wondered if he had come because he had been bullied or if he was the one doing the bullying, if they were victims or tormentors, the latter category being the bigger demographic. In my case, I was signed up because I was a victim. Well, also because my dad loved karate and because he wanted my sister and I to learn together. But mostly he signed us up because I was a victim.

Directed by John G. Avildsen and starring Ralph Macchio alongside Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, The Karate Kid was one of the most commercially successful films of the 80s. It tells how Daniel, a New Jersey teenager, tries to adjust to a new life with his mother in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Reseda. On his first night in town, Daniel flirts with an upper-class blonde cheerleader and ends up fighting her ex-boyfriend, a karate apprentice named Johnny, who along with his cronies devotes himself to bullying the new kid. After being assaulted several times, the concierge of his condominium, an old Japanese man named Mr. Miyagi, comes to Daniel’s aid offering to teach him the ways of karate in exchange for housework. Daniel is made to wax old cars and paint fences, chores that at first seem unrelated to karate, yet their usefulness comes to light as the film advances. Thanks to Mr. Miyagi’s training, Daniel is able to defeat Johnny in a karate tournament, where he is crowned champion and gets the blonde cheerleader. The moral of this film confirmed what would become one of the most recurrent bromides of Hollywood: with work and dedication the meek become the mighty. Which made a large audience connect with the film’s message that fighting back was the way to overcome bullying. But in real life this did not happen.

In my case, the bullying started as soon as my uncle joined the army. My uncle was a 6ft 5in giant who played center on a local basketball team. We shared a room so small that he had to sleep on one of those sandwich beds, so that every morning he could store it back in the closet. He could hardly fit on the bed; his legs hung off it and if at night I wanted to go to the bathroom, I had to be careful not to bump into them and wake him up. Given his imposing presence, no bullies dared mess with me. To the other kids whose pants had been yanked down in some corner, or who were thrown into garbage cans, or had various objects thrown at them, I was a privileged guy.

However, only a couple of weeks after my uncle’s departure, I became a victim of violence. I had gone out to buy my dad a half-pack of Marlboros, and on my way home I ran into Carlitos walking his doberman. This wasn’t the first time I encountered him and his dog, and usually it would bark while Carlitos clowned around with its leash. But I had never been attacked until that afternoon, when Carlitos let go of the leash. The doberman rushed at me and bit my right leg, and it might’ve ripped it off completely had I not been able to escape. My parents immediately heard me crying, saw the blood coming out of the wound, and once they grasped what had happened took me to the ER. While I was being treated, my parents called Carlitos’s house to find out if the doberman had been given a rabies vaccination. If not, they would have to stick a gigantic needle into my navel, like those used by aliens on their abductees. Carlitos’s mother wasn’t sure if the dog had been vaccinated or not, so the doctor injected me just to be safe, not in the navel as I had been warned, but in my shoulder.

It was usually difficult for my parents to spot any signs of bullying. This was because the neighborhood bullies rarely struck the face, since that would leave visible marks an adult would notice and report upon. Usually, if we were left with bruises, scars, or burns it would be on less visible parts of the body. Then one night, I came home bleeding from the nose. While my parents tended to my wound, I described how the person who’d hit me said he didn’t mean to do it.

“This was intentional,” my mother insisted.

As soon as the bleeding stopped, my dad brought out a few martial arts books from his library. He showed me some kicking and blocking maneuvers that I could use if confronted again, but when I did my assailants only increased the fury of their attacks. Finally, after I limped back home one evening, my parents decided to sign me up for karate classes. They also determined that my sister should be enrolled as well. I was terrified that having my sister accompany me to karate classes would only inspire my aggressors to come up with new ways to taunt and torment me. When one suffers from bullying, these are the sorts of considerations he has to analyze. But my sister was even more upset because she wanted to take driving lessons, not karate classes. Before my uncle enlisted in the army, he had been secretly teaching her. But the decision had been made, and that Monday, my mother appeared with two kimono.

The academy was located on the second floor of the Miramar club and consisted of one large room with cracked walls, rickety windows, and peeling roof paint. We could hear the shouts of the students from the street and when we arrived we saw them lined up to kick X-ray strike sheets that the sensei held out to them. Good kicks made the best sounds. This scene was quite similar to one from the film when Daniel enters the Cobra Kai academy with the intention of signing up only to find that students in training are the same ones who have been harassing him. There standing in line waiting for his turn to kick the X-ray sheets was Carlitos, with other familiar bullies behind him. There was no going back.

I figured I had two possibilities. The first was that my tormentors would grow bored with harassing me. The daily insults and shoving, however, were only getting worse. My other hope was that the sensei would intercede on my behalf. I’d based this idea on something the sensei had once said, that karate was a spiritual art and that its practitioners should never abuse the weak. But even though I sensed that he could see what was happening, he never brought the subject up again. It was uncommon for him to dispatch us with a motivational speech or some Mr. Miyagi-like Zen koan. Maxims were not his forte. Our sensei was much more attuned to his physical power. Which is why he would explain things with physical demonstrations. For example, he once piled bricks in the middle of the dojo, then squatted in front of them, keeping his eyes shut until the time was right to strike. Minutes later, when he had achieved the optimal degree of concentration (and our excitement), he uttered a shout, then smashed through the bricks with a single blow. Just like a Karate Kid scene.

Karate classes were on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 6–8pm. Our sensei would arrive 15 minutes in advance, and punish late arrivals with push-ups and crunches. If he was in a particularly foul mood, he would force these unfortunate students to complete a hundred laps around the nearby basketball court. Otherwise he would begin classes by having us do warm-up exercises, counting each rep out loud in Korean. Then we would practice striking, blocking, and kicking. After that, our sensei would divide us into groups for kata, a word that was defined in one of my father’s books—I’d looked it up after becoming curious about its etymology—as being ancient choreographed sequences of attacks and blockades. Near the end of training, we would sit in a circle as the sensei detailed these kata. Then he would tell two students to stand up to fight. These could be entirely random selections—a female against a male or an elder against a youth. In the academy, gender, age, and experience had no distinction. Each time I was called up, it was to spar with someone more advanced by at least a degree. The size, the sex, or the color of the belt, however, did not always guarantee triumph. In fact there was someone who had had very little training and yet no one was able to defeat, no matter how sophisticated their technique or maneuvers. That spunky undefeated student was my sister.

Carlitos was the first person to spar with my sister. It’s not that I feared anything would happen to her. Truth be told, she was much taller than me and the same size as Carlitos. Not only that, she was incredibly athletic and could be quite intimidating. But Carlitos was Carlitos, and I knew to be terrified. Early on, Carlitos had asked the sensei to make me his sparring partner. From then on, the sensei got the idea that I would always be made to fight Carlitos. And the last time we went against each other, Carlitos knocked me out. Well, okay, this had actually been my own fault. What had happened was that because our dojo would be sweltering, I tended to drink tons of water. One Thursday, I had been especially thirsty and drank until I was bulging. Of course, that was exactly when the sensei had me square off with Carlitos. I wanted to answer that I wasn’t able to fight, but no one had ever said no to the sensei, so I resigned myself to going against Carlitos, and waiting for him to knock me down with a crane kick, the same move Daniel does near the end of Karate Kid, which our sensei had forbidden. However, instead of performing this expected move, Carlitos surprised me with a low kick right in the gut. Miraculously I did not vomit. Instead, I lay stunned on the mat for nearly 20 minutes, surrounded by the other students as well as the sensei and my sister who were insisting that I get up. When the sensei realized that my injury was serious, he asked my sister to go get my mother and was about to suspend class, but out of fear of being scorned and labeled a “mama’s boy,” I shouted from where I lay for them to hold on. Gathering all my strength, I was able to stand back up. At the sensei’s suggestion, I shook out the pain until it subsided.

My sister would be Carlitos’s next opponent. They met at the center of the mat, bowed to the sensei, then to each other, before squaring off and commencing their fight. Well, it was hardly a fight, because my sister didn’t give Carlitos time to even breathe before she dropped him to the floor with a front kick. When Carlitos got back to his feet, the sensei told him to return to the circle and called someone else to fight in his place. Carlitos became so angry that he grunted and punched the wall. The sensei didn’t appreciate this attitude and ordered Carlitos to do 20 push-ups on the spot, followed by a 100 laps. This only bedeviled Carlitos further, who swore loudly as he departed down the stairs. He spent the next few days prowling around my house with the intent of getting revenge for being defeated by my sister, but once I noticed this, I stayed inside watching the whole cartoon programming of Telesistema. Back at the academy, my sister had become an unstoppable force and the sensei promised to take her to the championship taking place at the end of the month. At first, we thought that he only wanted to have her tag along, since my sister had only been in the academy for two months and wasn’t even a white belt. But one day, the sensei appeared with a poster announcing a karate tournament in the Los Prados Club, and that everyone in the Miramar Academy would be competing.

The tournament was held on a Saturday in the basketball court of the Los Prados Club, which had the capacity for the event. Many of the students, including Carlitos and his crew, did not seem to notice how this championship compared to the one that appears near the end of The Karate Kid. Yet it was as if the organizers had studied how Avildsen had filmed the scene and tried to imitate his set. Most of the students from our academy were beaten in the first round. I was disqualified for delivering a blow to some freckled doofus that landed below his belt. But my sister and Carlitos managed to advance to the semifinal. Carlitos ended up losing by a point, which caused him to fall to his knees and cry. The sensei was about to help him to his feet, but Carlitos suddenly stood up and kicked a metal folding chair with his heel. My sister, on the other hand, had gone all the way to the women’s finals. I did not understand how my sister was able to compete against blue belts, when she herself was unbelted. Had the sensei marked her for that category and then alleged that she had simply lost her belt? Who knows. In The Karate Kid, Mr. Miyagi steals a black belt for Daniel to use in the competition, so if that was possible in such a beloved film, surely no one would criticize if it happened in reality. Besides, given the kicks and dexterity that my sister displayed, no judge would have doubted that she carried a belt below blue.

Her final opponent was a braided black girl from the Los Prados Club. Because she represented the main team from the area, she was heavily favored to win. Even Carlitos who had been stewing with envy on the side of the premises cheered for her. Only a few of us openly supported my sister. When the two girls met in the center, a hush came over the crowd as every head turned to watch; it was so quiet you could hear their blows and grunts. It was an intense fight. Near the end, while we were all biting our nails, the sensei of the braided girl asked for a time out. From my sister’s corner, I could see the sensei giving her instructions. When they gave the signal to resume the fight, without so much as a second thought, my sister knocked her out with a single kick. She’d won. I remember feeling such joy: we threw whatever we had in our hands into the air and ran to embrace her. Then the sensei handed her the trophy, and we carried her on our shoulders back to the dressing room.

After my sister’s victory, Carlitos began to miss classes until he stopped coming altogether. I remember the last time he attended. We were doing push-ups, when suddenly, as if touched by some mysterious force, he got up and, ignoring the sensei, left without saying a word. In those days The Karate Kid was aired repeatedly on Teleantillas, and I came to realize how much Carlitos looked like Daniel LaRusso. In fact, he had taken advantage of this similarity and imitated Daniel’s character down to his smile, his gestures, his haircut, his clothes, his way of kicking a ball; he even wrapped a handkerchief around his head when he rode his bike. One surprising coincidence that I noticed was that, at the beginning of the movie, Daniel and his mother drive across America from New Jersey to Los Angeles. Carlitos made a similar journey with his mother, but instead of a car they would leave in a plane, and instead of leaving New Jersey, it would be their destination after leaving Santo Domingo. In the film the children of his Jersey neighborhood came out to say goodbye to Daniel; in the case of Carlitos no one saw him off.

When the sensei announced that the monthly fee for classes would be raised, my parents took us out of karate. My sister, who had achieved green belt, and who continued to triumph in the karate circuit, also had to leave and did so without saying much. The terrible Karate Kid sequels were to blame for the increased fee; the kids had lost interest in the martial arts and returned to their sedentary lives; that is to sit for hours tapping on their Nintendo and Atari controllers. By the beginning of the 90s the Miramar Academy had shuttered its doors. I never saw the sensei again. But my dad did when one morning he stopped in a café in El Conde for breakfast. After taking a seat at one of the tables in the back, he recognized the waiter serving the customers at the bar was our sensei. Instead of his kimono and his third black belt, he was wearing an apron. His hands, which could shatter boards and bricks, now slapped lettuce, tomato and cheese slices into sandwich melts. My dad decided that he would say hello as soon as he finished reading his newspaper. But at that same moment there must have been a shift change, because when my father raised his eyes back to the bar, the sensei was gone.

Copyright © 2017 by Frank Báez. Translated by Emes Bea. Read our interview with Frank Báez here.