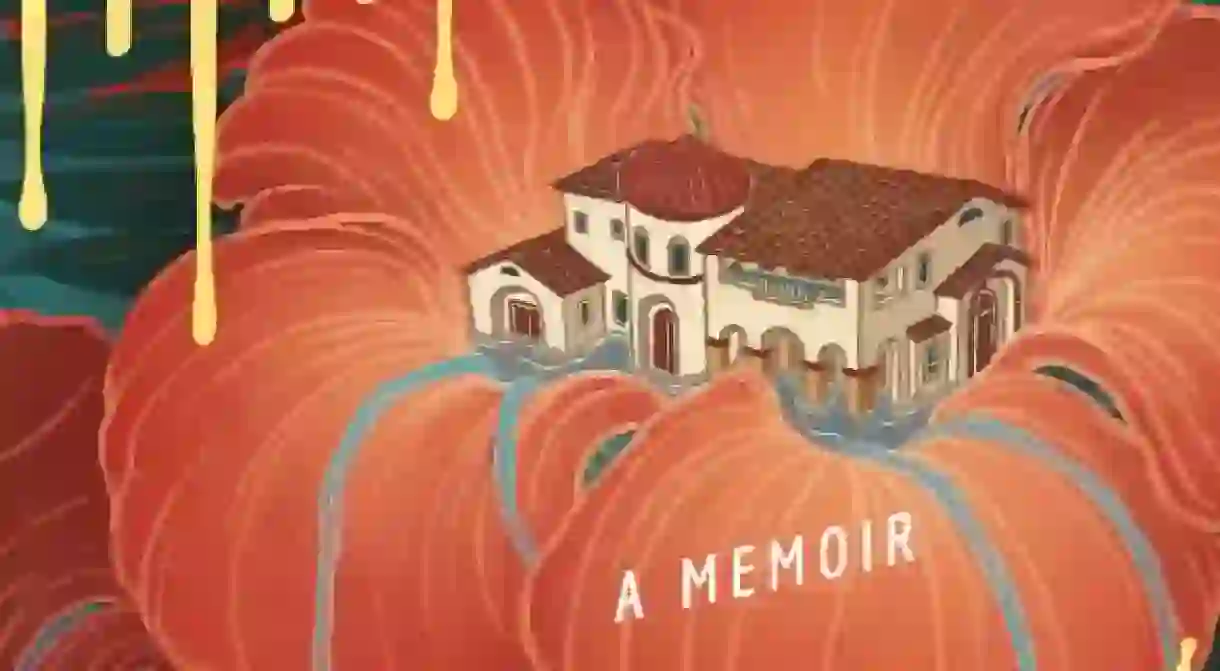

Read an Excerpt of 'Monsoon Mansion' a Memoir of A Childhood in a Philippine Mansion

Cinelle Barnes’s debut memoir is filled with the joy and pain of childhood. Set strikingly against the backdrop of Mansion Royale and the rich Philippine landscape, Barnes weaves the complex story of her family and the shifting dynamics that rocked her childhood. This memoir—a fairy tale turned survival story—strikes at the heart of what it means to grow up and face the reality of family.

Monsoon Mansion: A Memoir by Cinelle Barnes

Prologue: Mansion Royale

My parents named the house “Mansion Royale,” a stately home in a post-Spanish, post-American, and newly post-Marcos democracy. They bought it together with my mother’s inherited wealth and my father’s new money. It was the eighties, when bigger was better, and better meant glitter, gold, and glam. Our family moved in when I was two and a half years old, in 1988, when my first narrative memories were forming. The house became the setting for the first moments of mundaneness, celebration, and terror that my developing brain could retain.

The original owners of the house had their marriage legally annulled halfway through construction and put the mansion up for sale. They left some good bones for my parents to work with. My parents paid cash for a short sale and tipped big bucks to the real estate agent, and the mansion was theirs—ours: a palace that housed Mama’s social aspirations and Papa’s business success and the miscellanies that were the staff, my half brother Paolo, and myself. The mansion also housed many conversations—some in English, some in Taglish (a fusion of Tagalog and English, the upper class’s preferred tongue), some in straight Tagalog (the help’s lingua), and a few borrowed throw-ins from Old World Spanish and island dialects.

Our family entered through wrought-iron gates that were guarded by armed security staff. Flattened metal bars curved to golden swirls sprawled from one hinge of each gate door to the other, and although outsiders could look through the gaps between the swirls, the half-ton gates kept us separate from lookers and passersby.

Past the gates, our driveway stretched from the entrance, around the front lawn, through the shaded dropoff, down to the basement parking lot, then around the back to the basketball court. When my mother threw parties, the driveway turned into a meandering buffet of shrimp cocktail, fondue, roasted whole pig, beef Wellington—and barrels, bottles, and goblets of alcohol. The winding shape of the driveway was perfect for the zigzagging drunks who sauntered through.

Twenty marble steps welcomed us into the main floor, which was a story above the lawn. I learned how to count to twenty on those steps. “One, two, three, four, five, I can do it. Don’t hold me, Yaya, I can do it. Six, seven, eight, nine, ten.”

A woodworker carved on the main double doors a gold-plated relief of sinewy, thorny florae: plant carvings on the doors resembling the offerings in our gardens—birds-of-paradise, tropical orchids, bamboo, Indian mangoes—but spinier and barbed, as if they were about to hiss. The real plants, on the other hand, smelled fresh like a waterfall and didn’t look so much like snakes. The mansion was like that—it housed many contradictions: my aristocratic mother and self-made father, our family’s dependence on wealth and our helpers’ faith, and many adults’ agendas and my childhood dreams.

Inside the main doors, a gold-framed mirror the size of a small car hung over a console, where guests adjusted their ties and posture. My mother retouched her lipstick in front of it before leaving the house each morning.

In the grand ballroom, I played princess. It was the most spacious part of the mansion, a gold-plated square the same size and opulence as the historic Manila Hotel Centennial Hall. The walls sparkled in sand-colored stone, and the floor gleamed in an expanse of pearl-and-oyster marble, a mermaid’s castle. Stone terraces extended from the ballroom and the top floor. Bare of furniture and décor, the terrace was the ideal place for pondering the world outside. The terrace overlooked a fishpond and a rice paddy, where a farmer, along with his wife and sons, grew and harvested the Philippines’ staple foods. I watched them from the terraces, wondering how and why they withstood the sun’s heat.

“A young lady like you should never be out in the sun. Besides, you’re already dark. Too dark. We have to keep you out of the sun or you’ll look like those poor farmers,” my mother would say. This was the same reason I never learned how to ride a bike. But when she wasn’t home and the nannies were glued to the screen watching a telenovela, I walked out to the terrace and let the wind—which carried the little brown birds hovering over the paddy—blow my hair, whisk my skirt up, and sway me.

On the terrace, I heard the ancient church bells of the convent next door, where the nuns prayed the rosary and sang the Hail Mary in unison.

Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with Thee. Blessed art Thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of Thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death.

Then a full, long, resounding in-unison high contralto: Aaaaaah-mmmehnnn.

Papa adored their singing and rewarded them with regular rations of rice. Their hymns and invocations became my background music; they were the accompaniment to the stages of life in the mansion—the soundtrack to my preschool, grade school, and preteen years. The nuns created for me a holy atmosphere, a sheltering sound where I could abide. Wherever I was, as long as I could hear them, I had somewhere to hide.

My father made his money in the dining hall. He had an office, yes, but that served as storage for typewriters, contracts, blueprints, and ledgers. The real work took place where we ate, where he and his kumpares feasted over coconut crab, lobster, and bouillabaisse. The oval dining table seated at least twelve—where my father made eleven other oil investors and manpower recruiters richer. Not that their houses in Hong Kong, Dubai, and Singapore weren’t large enough. The oil and manpower recruitment industries were stable and booming. The men were merely bored. So when the Gulf War started, they were all shaken off their thrones. The oval table had no corners for them to hold on to.

“What’s a meal without a drink?” my parents would say. That’s what the bar was for. Not a trolley with an ice bucket, but our own taproom playing Christopher Cross and Spandau Ballet. What my parents lacked in musical knowledge, they made up for in their collection of beer, wine, and Rémy Martin. I never told them, but my brother occasionally stole San Miguel beer from the cooler. I, on the other hand, was always good. I only asked the bartender for Shirley Temples. I drank them on the barstool in my crinoline Marks & Spencer dress, my yaya holding me so I wouldn’t fall. She often gossiped to the bartender about our family. Si Misis nanglalalake, si Ser wala nang pera. The missus cheats on her husband; the mister has no more money. I always heard what she said and, worse, I understood.

© [Little A] Extract from Monsoon Mansion: A Memoir by Cinelle Barnes, published by Little A on the 1st of April 2018, available in hardback and eBook formats, $24.95