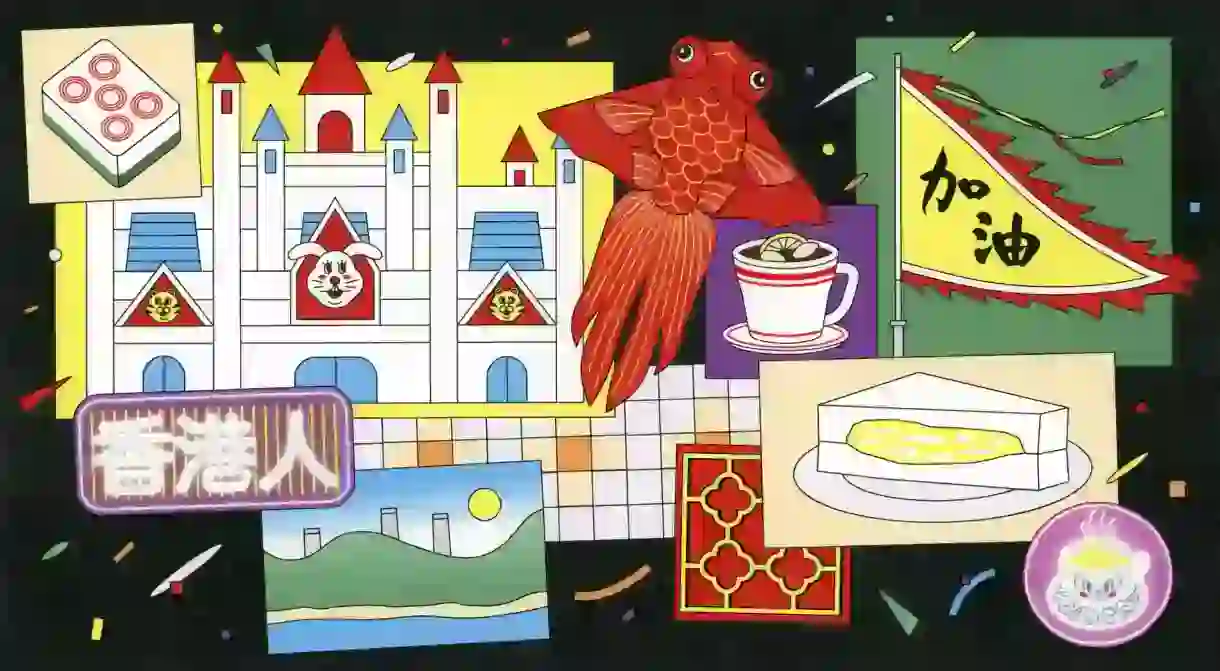

Why Hongkongers Love Hong Kong

What does it mean to be a Hongkonger? Explore this intriguing city on the cusp of change through the eyes of six locals who each love it in their own, very personal way.

Causeway Bay is less crowded than usual. It’s the day after Hongkongers in the area, rallying for increased political autonomy, were dispersed with teargas. Yet one of 27-year-old media professional Anna Chiang’s abiding Hong Kong memories is of safety. Walking along Yee Wo street, she recalls the exhilaration she used to feel as a 14-year-old, strolling home from Causeway Bay to Central at night after school. “I would walk through the neon-lit buildings and along the harbourfront, and be awestruck by how exciting yet safe my city was,” she says.

As a student, Chiang learnt that Queen Victoria’s foreign secretary Lord Palmerston referred to Hong Kong as “a barren island with hardly a house upon it” when Britain acquired the territory in 1841. “Palmerston saw Hong Kong as a fishing village with rocky, infertile land, and little hope of flourishing. But look how far we’ve come,” she says.

It’s the city’s cosmopolitan vibe that Chiang has always loved. “I’d go to Broadway Cinematheque in Yau Ma Tei, which only screens art-house films: movies by directors like Lars Von Trier. After a show, I would drink boiled coke with ginger at the nearby Mido Café, then walk down Temple Street Market through the bizarre and fascinating spectacle of fortune tellers and karaoke street singers. I’d feel like I was getting the best of both West and East.”

The impact of the 1997 handover

At Barista Jam, a brightly lit café in Sheung Wan, four friends in their 30s and 40s talk about HK’s past, present and future over over coffee and cake.

For 37-year-old recruiter Jeff Toh, the 1997 British handover of Hong Kong to China was a pivotal point: his family, uncertain about the Special Autonomous Region’s future, left in 1998 for Toronto. Many others did the same. But Toh’s family returned six years later, once they realised the city hadn’t been too negatively impacted by the transition.

Toh says that “Hongkonger” is a relatively new term that only gained traction post ’97. “When we were still under the British, many locals would say ‘I’m a Hong Kong person’ or ‘we are from Hong Kong’. The term only really took hold because we needed to differentiate ourselves from the people of other Mainland Chinese cities,” he says. “We’re proud of our unique heritage. Hong Kong people are hardworking and efficient. But to outsiders, our business-first mentality might seem brusque. This isn’t because we’re rude, but because we’re used to moving fast, always having to hustle to earn a living because this is a really expensive place to live.”

Forty-seven-year-old IT sales executive Sandy Chan and 45-year-old photographer Buzz Kwok talk fondly of an older HK, when the city moved to a slightly slower pace. They reminisce about the now defunct Lai Yuen Amusement Park – now Lai Chi Kok Park – where you could visit the ghost house or ride the Ferris wheel, and of the former peacock enclosure in Victoria Park. “We’d all go to Victoria Park and wait for one of the peacocks to open its tail. We had seen it so many times before, but still, every time the bird showed its colours, we would all clap,” laughs Chan.

Hong Kong, the big village

While certain places from the past are gone, both Chan and Kwok are glad that little has changed in other areas such as Sham Shui Po, where one can still walk down Yu Chau Street – an entire street devoted to haberdashery beads that has been around since the 1950s – or tuck into local favourites such as pig liver noodles at Wai Kee Noodle Cafe. The two women also enjoy playing mahjong at one of the parlours near Shanghai Street in Yau Ma Tei. “People book these spaces because, when they play at home, the neighbours often complain about the noise,” says Kwok.

Kwok recalls Hong Kong’s public housing estates of the ’80s. “Before, all the kids would play hide and seek together. It felt like a big village. The nearby shops even allowed residents to buy rice on credit. There was a strong sense of community and trust. Unfortunately, this is disappearing. Nowadays in the luxury condos, neighbours don’t even say hello to each other,” she says. “There’s a Cantopop song called ‘Below the Lion Rock’ that’s become the unofficial Hong Kong anthem,” Chan chips in. “This song tells us to ‘keep watch and defend each other’. The message of the song is what we Hongkongers call ‘the spirit of Lion Rock’. I sometimes worry that this spirit is diminishing,” she says.

Thirty-six-year-old editor Judy Ngao – who left Hong Kong for Visalia, California with her family in 1997, returning six years later – describes her “complicated” relationship to her home city.“Sometimes I feel it’s overcrowded and there’s too much construction everywhere. On such days I think of leaving. But most of the time, I love it. I love the geography – we have hills, waterfalls, beaches and forests – the culture, the people, the food, and the multiculturalism and dynamism.” When her friends from California visit, Ngao takes them to Tung Po, on the top floor of Java Road Market for an authentic Cantonese seafood dinner, then to belt out tunes at Junels, a ‘karaoke restobar’ in Sai Ying Pun. “Karaoke is a really popular local pastime,” she says. If friends visit during the Dragon Boat Festival, she’ll rent a junk so they can watch the energetic dragon boat races in Aberdeen or Stanley up close.

The beauty of being culturally mixed up

Hong Kong is also home to many Third Culture kids such as 34-year-old Boris Meyer, whose father is French and whose mother is a Hongkonger. Meyer was born in Paris, but moved here when he was just one year old. He’s now an account manager with an international global mobility firm in the city. “I speak Cantonese, English, French and Mandarin. When I was very little, my mother watched Cantonese soap operas on TV, but then we got cable and started watching American shows like Cheers. Sometimes I feel like a boiled egg: yellow on the inside, white on the outside,” he says, tucking into a lunch of shredded pork and mushroom fried noodles at the well-known Tsui Wah restaurant.

Meyer admits that, while he’s culturally “mixed up”, he’s a hundred percent Hongkonger. His best childhood memories are of kicking shuttlecocks with his uncles and cousins during family BBQs at Tai Mei Tuk, then riding his bicycle up and down the Plover Cove Reservoir dam. He also remembers flying kites at Lamma Island Lookout while contemplating the three incongruous chimneys of the Lamma power station across the sea. His favourite nature spot is Big Wave Bay in Sai Kung.

While dim sum is the go-to cuisine for most visitors, Meyer says no one should skip a scrambled egg breakfast at a typical Hong Kong bing sutt – an old-fashioned type of air-conditioned local eatery that provides light meals and non-alcoholic drinks. Even though scrambled eggs are pretty standard fare in most parts of the world, Meyer explains that bing sutt-style scrambled eggs are inimitable. “These eggs are silky, unctuous, and more delicious than anything you could whip up at home. I’ve tried replicating it myself numerous times by cooking my eggs on high heat with lots of butter, or low heat with some water, or other ways, but it never turns out the same. So I go to bing sutts like Café Seasons or Chrisly Cafe at least once a week.”

Perhaps Meyer’s beloved bing sutt eggs are an apt metaphor for Hong Kong – you can scramble East and West in any other city, but it’s unlikely that the results will be quite as spectacular.