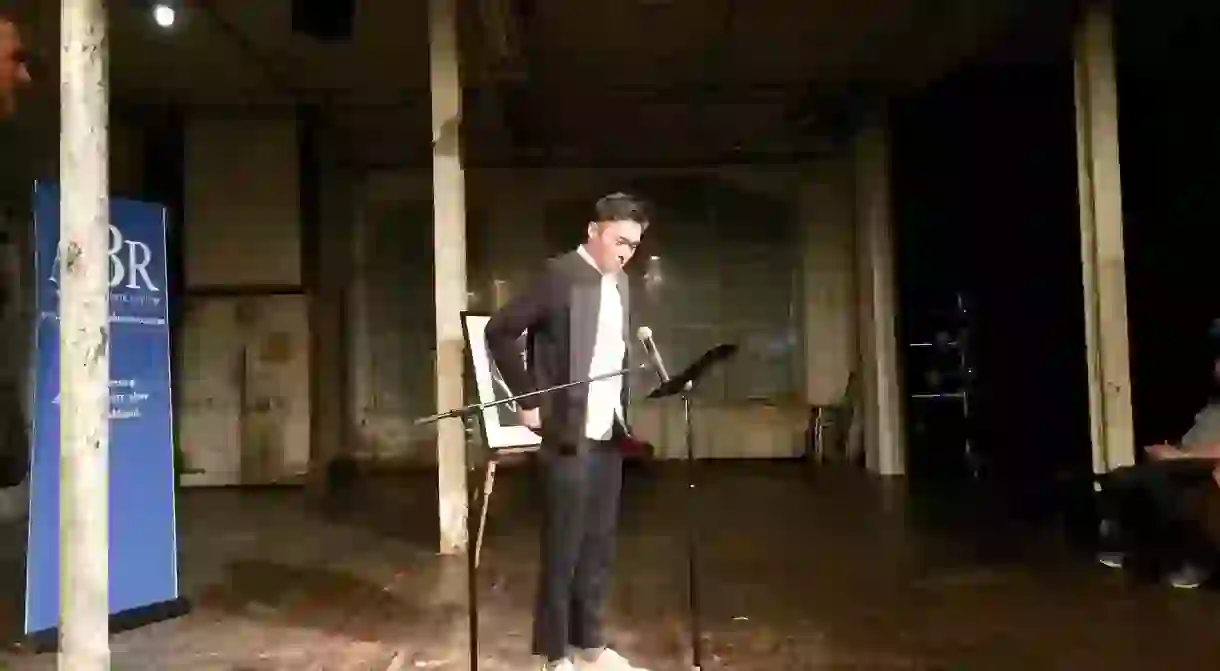

Nicholas Wong: Award-Winning Hong Kong Poet Shines Spotlight on Homegrown Poetry

After scooping a handful of international prizes for his poetry, Nicholas Wong is fast becoming a beacon of hope for Hong Kong’s local literary scene. Here, he discusses his work, what inspires him, the local poetry scene and the pros and cons of life in Hong Kong.

A thriving literary scene is not the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Hong Kong, but one man is well on his way to changing that. Local poet Nicholas Wong was born and raised in the city and his work has received international acclaim.

Most recently he became the first Asian poet to clinch the prestigious Peter Porter Poetry Prize in Australia, scooping up $5,000 with his winning poem titled 101, Taipei (featured below). This award follows his win at the 28th Lambda Literary Award with his poetry collection Crevasse, making him the first non-American winner in the award’s history. It’s hoped that Wong’s international success will encourage the Hong Kong government to do more to promote the local literary scene.

Meanwhile, we seized the opportunity to chat with Wong to find out more about his award-winning poetry, inspirations, and his take on life in the city he calls home.

How does it feel to be the first Asian poet to win Australia’s premier prize for poetry?

It’s certainly an honour, given the long history of the Australian Book Review, the prize and the body of Australian poetry. As a poet writing in his second language from Hong Kong, I’m already very used to the sense of being dislocated. My work brings me away from home, while I mostly do my writing in my home city. Dislocation, though disturbing, can be productive (or even pleasing) at times.

Is it encouraging to see your work crossing borders, countries, and cultures while receiving such high praise?

I do think the literary exchange between the multicultural and multilinguistic aspects of most Asian countries and Australia has so much potential, while the States (the biggest poetry publication market, in theory) is still predominantly inward-looking. Penguin Australia published a series of prose works called Hong Kong Stories, commemorating the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China last year. The volumes in that series (such as Anthony Dapiran’s City of Protest, Xu Xi’s Dear Hong Kong: An Elegy for a City and Dung Kai-cheung’s Cantonese Love Stories) are amazing.

Your winning poem was titled 101, Taipei – what are your personal thoughts about the Taipei 101 building? Was it your inspiration?

I don’t have much feeling about big tourist sites, regardless of where they are. However, I can’t deny the fact that given the recent political shape of the city, most Hong Kong people in my generation and the younger ones – especially literary writers – do visit Taiwan very often. While the actual 101 tower in Taipei doesn’t give me any inspiration, I used it as an architectural marker to initiate a poetic scenario about (perhaps my desire for) dislocation and the madness of it. I should also mention that I was planning to simply call it “101,” which bears a bit of queer subtext.

What are your views on the current Hong Kong poetry scene?

There are many amazing young and mid-aged poets writing in Chinese, and many of them deserve to be translated and read by readers who don’t know the language. However, I wouldn’t say the English scene is as interesting. Let me put it this way – we just have to admit poetry isn’t for everyone. And it’s the exact reason why people doing it have to do it right, from critical editorship to cover design, from promotion to publicity and distribution. The English poetry publishers just have so much to work on regarding these. This said, the local bilingual poetry magazine Voice and Verse has been publishing very engaging contents in recent issues. And I’m very happy to learn that a queer poet named Mary Jean Chan (originally from Hong Kong and now pursuing her PhD in London) will have her debut collection published by Faber & Faber very soon. I can’t recall if Faber has published any Asian poets recently, if at all. It’s certainly very exciting.

Would you say Hong Kong is a good place to be a writer?

It’s hard to say if Hong Kong is a good city for writing. It depends on whether one can cope well with the rhythm and density of the place. Some find it intimidating, whereas I am okay with it, because I don’t seem to have a choice of leaving the city for good. But the city always has a problem about sustainability. Hong Kong may not be an ideal place to sustain the career of a writer, because there are hardly any literary agents.

Are you ever inspired by Hong Kong?

I am more fascinated by Cantopop songs (cultural products of Hong Kong) than the city itself. I like the packed melody and lyrics. I grew up with them, and I suspect the genre has somehow affected the way I handled the form of my poems: the line breaks, the turns, the spacing, or even the length of a line.

You were also the winner of the Lambda Literary Award in Gay Poetry – are there still challenges of being gay in East Asia? Does your work ever broach these topics?

Winning the Lambda with my poetry collection Crevasse is a key moment in my writing career, but let’s not forget that being queer (or gay, in my case) is a rather generalised saying, by which I mean if you want to maintain a certain lifestyle of consumption, East Asia has it all – the bars, the fashion scene, the body… However, approaching my 40s, I am more and more aware of the psychological well-being of being gay at my home city. East Asia is simply so behind in this, and everyone is now excited to see how the same-sex marriage laws can engage the entire Taiwan and other neighbouring places further into the discussion of equal civil rights among all.

Despite the fact that Hong Kong will host the 2022 Gay Games, there’s still no anti-discrimination law in the city to protect sexual minorities. Have I ever approached these issues in my work? I think journalism and creative non-fiction can better illustrate them. Poetry that singularly confronts those issues may sound too didactic; that isn’t how I write my work. This said, the impact of such issues always leaves an imprint somewhere in my head and operates the atmospherics of my lines. I often find my recent work dealing with the theme of entrapment. I like to explore and create in the space between force and counter-force, and how one’s desire and language works together as consolation.

101, Taipei

after the Mandopop song ‘Centrifugal Force’ (Yang Naiwen, 2016)

Happiness in wanting to say something but not saying it. I want to say

happiness in a way others cannot. You look up at my blue-green glass,

double-paned and glazed, and think we, even when someone

jumps, are never on the sane page. Of course, I look like

a huge magic wand that grows a sad rose. Yes, the rose

is dyed, at best. No, there is no rose. I, who have grieved

for the softness of streets replaced by purpose and shops, know

you will one day lie face down with your beautiful eyebrows.

Others think the body bag that does the job is plastic art,

but it is the zip, its reverence tossing us away from the implied

cause. Do you know the 21st century took our belongings inside?

If, as Mary Ruefle says, we are to be exact with the price

of a thing (be it a rooster plate, a kind rope, or, better, songs

about life not smooth as a tattoo) by adding 99 cents

to what it is already worth to make it feel more real,

you wonder what the steel of that one senseless floor

is for. For long, I have become where your soft spots

whisper We are metaphors or Take us, before, all winter long,

raw anticipation aches, sees nothing. An unbecoming. To some,

it is less sad. I am still the same set, same scene and torque

groping and tending the moon in Ourselves. Their selves.

To you, just another phallus? One that jokingly stands.

All seasons are equally good for waiting and missing out –

how you are here early, as if waiting for the world to come

down with its legs up, for the thing in your head to be heard.

It is hard to see a swaying hand in a crowd; everyone now crawls

towards everyone less sad-looking. Yes, the rain gets you

nothing. You are a living construct that mellows street lights.

Shouldn’t you be going home, where questions are decades old?

The ones you are expecting will not come. They are a list

by a kid to keep you soaked to the bone – the star

barista, the edgy clerk, the entrepreneur who burns

family pictures. People come with their cameras to frame

the circumference of their open despair. I close a door

behind you, but it is conservative to say only the natural world

matters. I am famous. I appear in maps. Come,

didn’t you say I speed up happiness with a city view?

Beneath me, a male world thrums with every strung kind.

With kind permission of Nicholas Wong and Australian Book Review.