Bahia Mahmud Awah Spoke to Us About His Relationship to the Western Sahara

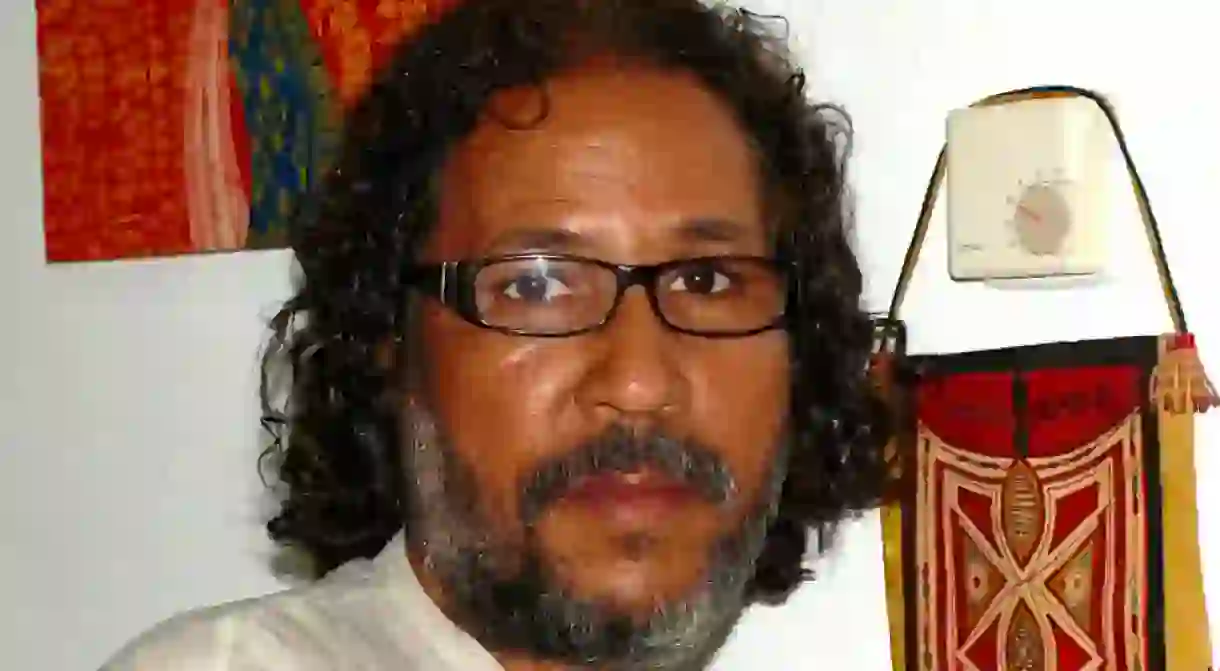

The Saharawi writer from our Global Anthology was joined by his translator to talk about his work and activism.

In 1976, Spain formally ended its occupation of the Western Sahara. In its place rose two flags, that of Morocco, which claims the territory as its southern region, and the Saharawi Republic, which declares the territory to be an independent state of the region’s indigenous people. The dispute, which continues to this day, along with the national history and national identity of the Saharawi people, preoccupies the work of writer, academic, and activist Bahia Mahmud Awah. Born in the rural commune of Auserd, Awah lived the traditional life of a Bedouin nomad until being sent to a formal school. His education, coupled by lessons his mother gave to him at home, nourished his love for literature and a pride in his heritage. In 2011, Awah published La maestra que me enseñó en una tabla de madera (The Woman Who Taught Me on a Wooden Slate) a literary memoir that recalls his Bedouin childhood and his mother’s instructions under a backdrop of the history of the Western Sahara from the Spanish colonial era to the Moroccan occupation. Well received in Spain, the book’s translation has been overseen by the Canadian/Ghanaian scholar Dorothy Odartey-Wellington. An extract from this translation “How My Grandfather Almost Starved to Death” is the Saharawi Republic selection for our Global Anthology.

We spoke to Awah and Odartey-Wellington about the book, the history and current state of the Saharawi Republic, and what it means to be active toward the cause of sovereignty.

* * *

“How My Grandfather Almost Starved to Death” is a memoiristic work that reads like novelistic prose. Could you tell us more about how you came to write it?

It was my mother who first taught me the alphabet back when I was a child in the 1960s. She used the same wooden slate that the Saharawi people used to memorize poems and religious verses. I had a close relationship with her as my tutor, which also made her my intellectual mentor. I was not with her when she passed away in 2006; she had been living in exile in Algeria and I myself was living in Europe. I not only felt the loss of my mother, but also of the nurturing source of my literary writings and childhood memories. I decided to write a biographical tribute, so that people would be made aware of her accomplishments as a poet and scholar of our African culture. I set out to create this literary work about her life and aspects of her literary work. It is the best homage that can be paid to the teacher who prepared one for the future.

Much of your book takes place when the Saharawi Republic was still part of Spanish Sahara, which was abolished when you were still a teenager. What do you remember of that transitional period and how much of it has impacted your life and writing?

Unlike the children of the city, my memories of that period are those of a Bedouin boy — I was more mature and better prepared by the vicissitudes of nomadic life coupled with living in small towns both on the African coast and within the interior of the Sahara desert. But my fondest memories are of mother and our family in general. I remember, for instance, the day she took me to enroll in the first schools that were set up in a military barracks so that I would learn to read and write in Spanish as well as Hassaniya. I also had the opportunity to experience the final years of the colonial period. I can still recall my father wearing the Spanish military uniform of that era, as well as the Spanish flag waving over our buildings and small desert towns. Fortunately, during that time my older sister and my mother also instilled an anticolonial awareness in me by raising the flag of the Saharawi Republic and the Polisario Front. By the time the Spanish were on the verge of leaving, around 1975 and 1976, the names of Nelson Mandela, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, and other African anti-colonial leaders had reached my consciousness. They became my inspiration to join the struggle for the decolonization of Western Sahara. But the other fond memories and images that I carry with me are from my years as a shepherd boy, when I combined school with herding camels.

Like your grandfather, you’ve lead the life of a modern nomad, particularly as an academic and are now a professor at the Universidad Autonoma de Madrid. In what ways do you remain active with the culture, society, politics and fate of the Saharawi Republic while remaining physically outside of it.

Engaging with these memories by writing stories, essays, and poetry helps to preserve my Saharawi identity and nomadic heritage. I’ll give you a couple of examples from what others have said. For instance, my friend and thesis supervisor, Professor Juan Carlos Gimeno, once wrote of my work: “Bahia’s challenge is that his books are oral, he writes about oral stories. He tries to serve as a mediator between oral and written narratives, and to engage in a dialogue between Saharawis of different generations, in an attempt to preserve this oral heritage in writing.” Luis Leante, a friend and writer who wrote an introduction to one of my books, noted of my writings: “Bahia recounts his experiences of childhood, the memory of his home and traditions, the desert, and recent history. Memories are of great importance in exile.” I believe in the evolution of our world, in its constant transformation, but I cannot understand the future without the past. And that is why my texts are grounded in stories from Saharawi history, so that new generations can understand our current reality and our future.

Dorothy, perhaps you could talk a bit about how you came to translate The Woman Who Taught Me on a Wooden Slate?

When I read it, I was motivated to translate and share it with a wider readership for several reasons. Firstly, I was struck by Bahia’s tender portrayal of his mother. Secondly, although the book was inspired by his mother, to whom he attributes his literary sensibilities, it seems also to be a tribute to African women. It gives readers an insight into the important role of women in the Saharawi nomadic society and thereby dispels some of the stereotypes of African women in popular media. Furthermore, the book is also a lyrical portrait of Saharawi society, its literary culture and its struggle for independence from Morocco’s occupation. In that sense, it is representative of contemporary Saharawi literature. Additionally, reading La maestra is like peeling an onion; underneath each story, lies layers of insights and themes that, in my opinion, have universal appeal. For instance, the account of how Bahia’s grandfather survived the sandstorm with his camel is a story about perseverance. But, it is also a story that illustrates the symbiotic, ecological and humane relationship that ought to exist between human beings and their environment.

How did you two come to work together?

DOW: I first connected with Bahia about ten years ago. That was at a time I was looking for information on Saharawi writing in the colonial press of the Spanish Sahara. I had contacted him because as a founding member of the Generación de la Amistad Saharaui he featured prominently online as one of the key representatives of Saharawi literature and culture. Subsequently we met “digitally” when he gave a plenary talk during the first online conference on Afro-Hispanic literature and culture that I organized in 2013. We finally met in person in the summer of 2015 when I went to Spain to interview him and other Saharawi writers for my ongoing research on Saharawi identity and culture. Prior to that meeting however I already had the sense that I knew Bahia quite well because of the time that I had spent on his work, in particular on La maestra que me enseñó en una tabla de madera.

Do you see translating Bahia’s work as a somewhat political act?

I am translating Bahia’s memoir to enable that and contemporary Saharawi literature and culture in general to reach a wider readership. As writers, whose homeland is currently occupied by Morocco and who have been forced into exile in refugee camps and elsewhere, Saharawi writers face enormous barriers to having their voices heard. I am interested in bringing those voices to people who are unaware of the Saharawi cause and of contemporary Saharawi creative expression. I view my translation more as an act of solidarity, although it can also be seen as political.

You are a founding member of the artist and activist collective “La Generación de la Amistad Saharaui” (The Saharawi Friendship Generation), a group that was featured in a the documentary Life Is Waiting. Could you discuss the missions of the group and some of its activities and members?

We founded the Friendship Generation, in July 2005 in Madrid, as a platform for intellectuals devoted to the process of Saharawi national liberation . The group is made up of two generations: the one to which I belong was born in the Sahara during the Spanish colonial period, attending high school when Spain was still with us. Consequently, we remember, and also have a close bond with, the land and its history. On the other hand, the other members had only just been born or were very young when the decolonization process began. Therefore, they hardly have any memory of the land. As for our individual activities, we have been able to bring our national cause to the Western and Latin American worlds through cultural forums, book publishing, and participation in international conferences. We have succeeded in placing our Afro-Arab-Hispanic culture on the agendas within the milieu of the Hispanic academic, editorial, and cultural world in general. This, I believe, is one of the functions for which the Friendship Generation was born. I am an anthropologist of my culture, I am a poet of my culture and, of course, I am a writer and a cultural activist. In one way or another, this identity reflects my political engagement with the Saharawi cause. I hope to free myself from the label of “exiled person”. And that will happen when we regain total national sovereignty over the land of the Western Sahara.

The poet Gabriel Celaya said in regard to this idea and I agree with him:

I curse poetry conceived as a cultural luxuryby neutral peopleWho, in washing their hands, seek to disengage and evade.I curse the poetry of those who do not become stained because they do not take sides

My poems and my writings express my political and social engagement with, and my passionate love for, my land and for its cause.

What are you currently working on?

I have just finished my Master’s degree in Public Anthropology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, where I am an Honorary Professor. And I often attend conferences at universities all across Europe where I discuss my books and various projects I am working on, all of this is, of course, in addition to to my media and cultural activism.

DOW: In addition to translating La maestra, I am working on a book project focused on Saharawis’ notion of national identity outside their territorial borders. An aspect of the project, an article titled “Walls, Borders, and Fences in Hispano-Saharawi Creative Expression”, is forthcoming in Research in African Literatures.