Brazil Soccer Stadiums: From World Cup Arenas to White Elephants

Despite the sensationalist news about stadiums not being completed on time, chaos in airports, and the threat of urban violence, the 2014 World Cup in Brazil was one of the greatest ever editions of soccer’s biggest tournament. Brazil’s love of the sport, their beautiful stadiums, the nation’s famous hospitality, and unflinching joie de vivre made the last World Cup unforgettable for every tourist that came to visit. However, three years on, the Brazilian taxpayers are not even close to paying off the most expensive tournament in history, and have received very little in the way of any positive lasting legacy. Of the 12 stadiums used, all but two are either unused, fraught with corruption allegations or have serious structural problems.

In the central-west city of Cuiabá, the $180 million Arena Pantanal is now being used as a high school. The national stadium in Brasilia is now home to offices for the local government. A landslide at the Arena Corinthians in São Paulo last year put that stadium at risk of closure and has been a financial headache for its tenant club, Corinthians. All three were built within the last four years. The Brazilian public is now asking whether it was all worth it.

A monumental own goal

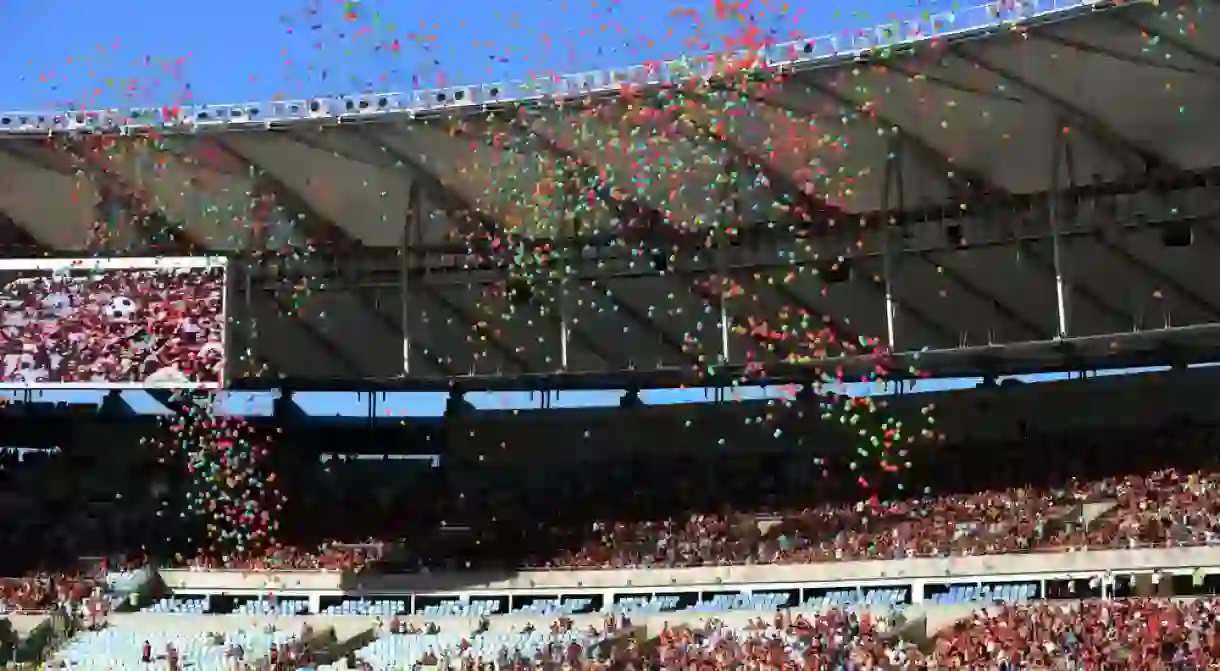

When it became known that Brazil would host the 2014 World Cup, work began on renovating the Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, one of the most iconic soccer venues in the world. There was never a doubt in anyone’s mind about the benefits of such a renovation: the stadium would be able to host a World Cup Final in 2014, as well as events at the Olympic Games two years later, and once the dust settled, local clubs Flamengo and Fluminense would make sure the new Maracanã was put to good use with regular matches.

In business terms, renovating the Maracanã was an open goal. Renovating the temple of Brazilian soccer would be expensive, but lucrative in the short to medium term. All the parties involved (local government, construction firms and Rio de Janeiro soccer clubs) had to do was roll the ball into the empty net. However, through a combination of incompetence and malfeasance, they managed to kick the ball way over the bar, out of the stadium and into the Guanabara Bay.

The initial agreed cost for stadium works was set at $210 million, but renovating the Maracanã ended up costing an incredible $360 million to the Rio de Janeiro state government, driving it to the brink of bankruptcy and causing a state of financial calamity. As part of ongoing federal police investigations into corruption within Brazil’s biggest construction companies, the firms responsible for the stadium works were charged with having overpriced contracts and rigging the bidding process for the construction contract.

These monumental costs aside, since the World Cup, the Maracanã has only been used a fraction of what was projected several years ago. Because of the massive overheads of the stadium, matches held there must attract a crowd of 30,000 fans just to break even. During the Rio de Janeiro state championships, the average attendance was below 10,000. As a result, the city’s big clubs have decided to play elsewhere, saving the Maracanã for only the biggest games.

An unwelcome gift

Any World Cup in Brazil would have to have at least one venue in São Paulo, the largest city in the continent. Initially, the expectation was that São Paulo F.C.’s Morumbi Stadium, the biggest soccer venue in the city, would be renovated and host the World Cup. However, the poor relationship between the club’s now-deceased president Juvenal Juvêncio and the top brass of Brazilian soccer put paid to any hopes of that happening.

Alternatively, one of the city’s major clubs, Palmeiras, had already signed contracts to build a brand-new stadium which would meet F.I.F.A.’s standards, and would be erected entirely using private funds. If the Morumbi was not to receive its much-needed reforms, then Palmeiras’ state-of-the-art Allianz Parque was the obvious choice to host matches at the World Cup.

However, the organizing committee decided instead to build a brand-new stadium for the city’s most popular team, Corinthians, a club which has never had its own grounds and for years played at a municipal stadium in the city center. The initial project was for construction giants Odebrecht to build it without any federal investment. However, in a situation repeated all over the country, stadium works went well over budget and the project received a huge amount of public money. Initially projected to cost $120 million, the building of the so-called Arena Corinthians ended up costing $360 million – three times its original estimate.

The first few years of the arena were also fraught with problems. During construction, a laborer was killed when a crane, operating on unstable soil, crashed and fell. Heavy metal panels from the stadium’s roof were blown off during high winds, landing in an area usually filled with soccer fans on match days. Last year, a massive water leak underneath the stadium’s car park was discovered, which put the surrounding area at severe risk of landslides.

Earlier this year, during testimony as part of the ongoing corruption investigations into Brazil’s large construction firms, Odebrecht’s former president claimed his company took it upon themselves to build the stadium as a gift for former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is a die-hard Corinthians supporter. However, no evidence has yet been presented and the ex-president strongly denied the allegations.

The white elephants in the room

One particularly curious part of Brazil’s World Cup preparations was the selection process for the tournament’s host cities. F.I.F.A. had requested eight venues, but Brazil was adamant on having a total of 12, spread all across this enormous country. The choosing of the dozen lucky cities took an incredibly long time and there is no shortage of sources who claim the entire process was politically motivated.

In the end, cities such as Manaus, Cuiabá, Natal and Brasília, places with little to no local soccer culture, were awarded World Cup matches and brand-new stadiums, while proper soccer cities such as Florianópolis, Belém and Goiânia missed out.

The choice of Manaus as one of the host cities was particularly controversial. In an effort to have the tournament spread out across Brazil’s five main regions, one of the World Cup venues was to be in the country’s north region. This means it was between Manaus – in the middle of the Amazon Rainforest, with no suitable stadium and zero local soccer culture – and Belém, the capital of the state of Pará and one of the most vibrant soccer cities outside of the south and southeast, with a massive stadium and two very well-supported clubs, Paysandu and Remo, to fill it once the tournament was over.

During the technical evaluation of the potential host cities, Belém was judged to have the third-best candidacy of all competing cities, only falling behind São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. However, at the end of the day, the organizing committee chose Manaus. Obviously, this had nothing to do with wanting to improve relations with Eduardo Braga, senator and former governor of Amazonas state. Also highly suspicious is the fact F.I.F.A. sponsors Sony and Coca-Cola have huge factories in Manaus.

As soon as the World Cup packed up and left, the brand new arenas in Cuiabá, Manaus, Natal and Brasilia went largely unused. In an effort to recuperate losses, the stadium in Cuiabá is now used as a high school, while its car park is used as a garage for the city’s buses.

It is yet to be seen what will happen to these stadiums, and corruption investigations are uncovering new evidence of dodgy dealings and malfeasance every week. One thing is certain, Brazil organized the biggest and most expensive World Cup of all time, and now it’s the Brazilian taxpayers who are being forced to pay the price.