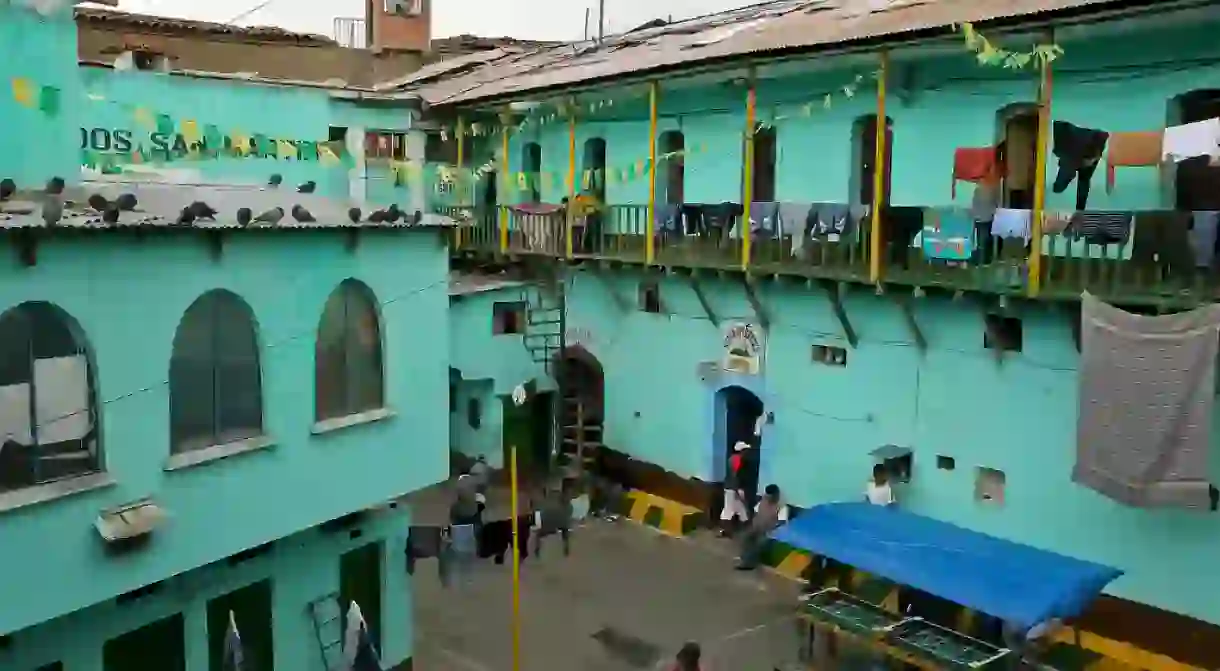

A Glimpse Inside San Pedro: Bolivia’s Self-Run Prison

Right in the heart of La Paz’ middle class San Pedro neighborhood lies one of the world’s most notorious prisons. Cárcel de San Pedro (San Pedro Prison) reached international fame in 2003 when Australian law graduate Rusty Young released his first novel, Marching Powder: A True Story of Friendship, Cocaine, and South America’s Strangest Jail. The bestselling book captivated readers for its harrowing insight into the lawlessness and corruption inside the now-infamous jail. After all, this is a prison that is completely self-run, where police only patrol the perimeter to thwart potential escape efforts, leaving governance entirely in the hands of the criminals inside.

Three thousand inmates cram into the chaotic prison that was originally designed for just 600. They are not assigned rations or accommodation by the state, instead relying on the generosity of family members or income from menial jobs on the inside. There are a number of employment opportunities inside the jail, from bar tenders, chefs, waiters and shopkeepers, to security guards, politicians and real estate agents. Some years ago, there were even guided tours given inside the prison. Corrupt guards would allow English-speaking guides to escort foreign tourists through the complex, some of whom stayed overnight to enjoy wild, cocaine-fueled parties.

Much like life in the free world, society inside the prison is divided into classes depending on the economic wealth of the inmate. The poorest reside in notoriously dangerous sections which are crammed full of addicts sharing with up to five people in a cell designed for one. But the quality of accommodation increases dramatically for those with financial means, with the richest living in fancy, gated communities that are segregated from the rest. Many of these are corrupt businessmen, politicians or narco-traffickers who enjoy luxuries such as flat-screen TVs, wifi, or even Jacuzzis.

The process of purchasing accommodation is surprisingly formal. Available cells are advertised on leaflets throughout the complex and buyers purchase their cells directly from the prison mayor or through a freelance real estate agent. Taxes must be paid on real estate to cover things like maintenance, security, cleaning, renovation, and even the occasional event. After agreeing on a price, titles are signed in front of an authorized witness who verifies the details and formalizes the transaction with an official seal. Prices range from US$20 for floor space in a cramped cell to US$5,000 or more for the prison’s finest apartments. Those who cannot afford to buy a cell can rent one for cash or in exchange for work.

The prison also has a remarkably well-structured political system. Each section has its own administrative officials who oversee housing, security, punishment and sanitation arrangements. Their salaries come from funds raised by internal fees and taxes, which are managed by the prison treasurer. A prison mayor is democratically elected on an annual basis, and enjoys the highest authority in the community.

Due to a lack of police presence inside the facility, large-scale cocaine production is undertaken to bring much-needed income into the community. Huge, elaborate labs produce what is said to be the country’s finest cocaine, while smaller clandestine operations produce just enough to supply the prison’s many addicts. The good stuff is smuggled out daily through visiting family members, a practice casually referred to as negocios (business). Unsurprisingly, addiction is rife throughout the complex. The majority of users smoke base, leftover residue from the production process that is highly addictive. Eighty percent of inmates are inside for drug-related offences, and 75 percent are still awaiting trial.

Women are forced to live on the inside with their husbands as they can’t afford to support themselves alone. Many bring their children with them, who only leave once a day to attend a nearby school. Life on the inside leaves the women and children vulnerable to abuse, resulting in frequent occurrences of rape. The worst of which caused the death of a young child whose perpetrator was later caught and beaten to death in what is known as justicia comunitaria (community justice).

The Bolivian government has been planning the prison’s closure for years now due to overcrowding, rampant drug production and the inability to protect innocent family members from abuse. It also happens to occupy a large portion of prime inner-city real estate, undoubtedly worth significant money. Upon closure, most prisoners will be sent to Chonchocoro, a notoriously harsh and strictly controlled prison in the impoverished city of El Alto. Every time the issue is brought up the inmates riot in a desperate attempt to protect their homes and community. As bad as San Pedro may seem, living conditions for even the poorest residents are preferable to those of Chonchocoro.