Football At 12,000 Feet? Welcome to Bolivia

In South American football, a region with nine World Cup trophies under its belt, it is no exaggeration to say that Bolivia is one of the continent’s weakest players, having qualified only three times (in 1930, 1950 and 1994) and scoring just one goal in its six World Cup matches. However, La Verde, as the Bolivian football team is affectionately known, has an advantage very few of its rivals can match—a height advantage.

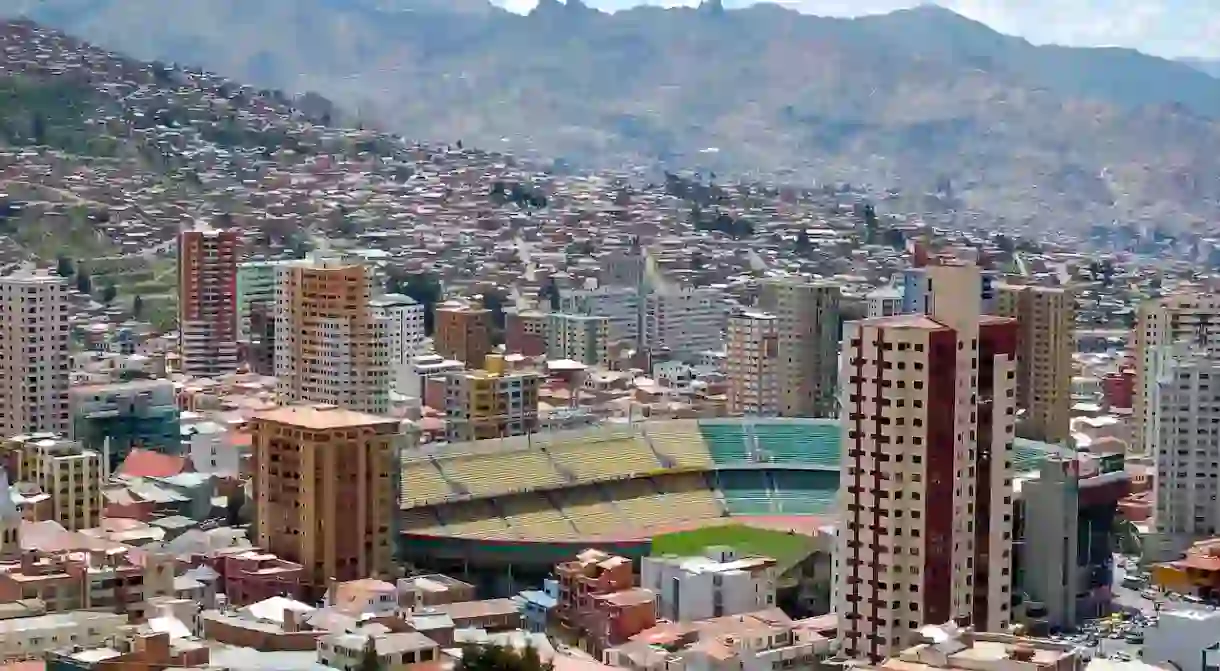

This is not to say Bolivia’s players are taller than their peers. On the contrary, its star player Alejandro Chumacero is only 5’5” (1.65 metres). The national team La Verde plays its home matches in the city of La Paz, which, at an altitude of almost 12,000 feet (almost 3,700 metres) above sea level, is the highest capital city in the world. For those who are not acclimated to these heights, any sort of physical activity becomes considerably harder when performed at such an altitude, especially professional football. As a result, Bolivia is one of the hardest teams to beat at home in world football.

The main issue with playing any sport at a high altitude is the percentage of oxygen available in the air. Even in extreme altitudes, air will always contain an oxygen level of 20.9%, but the barometric pressure is significantly reduced causing breathlessness in non-acclimated individuals. The movement of the ball itself will also be different: it will move through the air much quicker and be much heavier, reducing its bouncing abilities on the turf.

This combination of factors makes it very difficult for even the best football teams to perform well when playing in Bolivia, who’s national team was able to secure some historic wins on home soil such as the famous 6-1 victory in 2009 against an Argentina team of Lionel Messi, Javier Zanetti, Javier Mascherano and Carlos Tevez.

Speaking exclusively to Culture Trip, Bolivia’s first-choice goalkeeper Carlos Lampe explained how the Bolivian national team makes the most of its unique advantage. “We try to apply constant pressure on our opponents, playing as quickly as possible to make them run out of breath”, he said. “It’s really difficult for opposition goalkeepers to become accustomed to the speed of the ball, so we try to take a lot of shots from a distance and hit high crosses into the penalty box.”

As an example, a ball kicked 22 yards (20 metres) at sea level from the goal at 60 miles (97 kilometres) per hour to a height of 5 feet (1.5 metres) will lose almost half of its speed by the time it reaches the goalkeeper; in La Paz, the same shot loses only 30% of its velocity and rises to just under 8 feet (2.4 metres), making it much harder to block.

However, it is possible for visiting teams to become used to the high-altitude conditions of La Paz, though it requires a much longer preparation time than what is offered to professional footballers. Training at a high altitude for a number of days (usually 10) can increase the body’s maximum oxygen uptake, as well as its levels of red blood cells and EPO (a hormone that promotes the production of red blood cells), drastically reducing the negative effects of physical exertion in these conditions.

Many national teams over the years have experimented with the controversial tactic of travelling to Bolivia on the day of the match in an attempt to combat the onset of altitude sickness which often leads to headaches and irregular sleeping patterns. However, while it is true that playing on the day of arrival allows players to have a proper night’s sleep before the match, it also means they will feel the full effects of the altitude difference during the game itself. This was the cause of Argentina’s undoing in the 2009 game.

Another school of thought suggests that drugs such as caffeine, paracetamol and even Viagra can improve athletic performance at high altitudes, all of which have been experimented with by professional teams.

However, as Lampe describes, it is not only the visiting players that suffer playing in La Paz, many Bolivians who usually play abroad or in cities at sea level, such as Santa Cruz de la Sierra, also feel the negative effects of the altitude. “The first three days are really difficult. You get these headaches and it’s hard to sleep”, he explains. “Often when we play in La Paz, the coach will only pick those who are naturally acclimated, along with three or four players who play at sea level or abroad.” Lampe also plays club football for the Chilean team Huachipato.

There is an ongoing discussion about whether professional football matches should even be permitted at severe altitudes, keeping in mind the significant advantage of the home team as well as the potential health risks for non-acclimated players. In 2007, after the Brazilian team Flamengo played a continental match against Bolivia’s Real Potosí at an altitude of almost 13,500 feet (4,100 metres), the players of the away team were left clutching at oxygen masks. This led to the Brazilian Football Confederation lodging an official complaint to FIFA, football’s highest governing body, who imposed a ban on playing matches in cities with an altitude over 8,200 feet (2,500 metres) above sea level. A year later, after being pressured by Bolivia’s president Evo Morales, the ban was lifted.

“I don’t think we have an unfair advantage”, says Lampe. “Ninety percent of international teams have different types of advantages in their home stadiums. For example, when we go to play Venezuela, Brazil or Colombia, the heat and humidity is almost unbearable.”

Playing football at a high altitude seems to be here to stay, and Bolivia is looking to make the most of it. In July 2017, a new football stadium was opened nearby La Paz in El Alto, the highest major city in the world at 13,600 feet (4,200 metres) above sea level, and it may be used by the national team in the future.