Decolonizing Columbus Day in the Americas

Christopher Columbus wasn’t considered a hero by everyone. Find out why different countries and some states in the US have changed the name of the holiday known as “Columbus Day.”

On October 12, 1492, an Italian explorer named Christopher Columbus arrived on the shores of the “New World.” He meant to exploit the lucrative spice trade in the East Indies, but instead he introduced colonization to the Americas – an event that would forever change the course of history on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

This colossal historical event is still recognized in some North American states, as well as many Latin American and European countries. However, it’s not without controversy. While for some Europeans and North Americans this day marks the expansion of the Western World, for indigenous people it serves as a reminder of what was to come: hundreds of years of genocide, slavery, and cultural repression.

In an attempt to reclaim the day their lands were “discovered” by foreign powers, countries across Latin America (as well as certain states in North America) have renamed the holiday – and have instead shifted the focus from glorifying Columbus and his “Discovery of America” to honoring the bravery of the victims of colonialism, as well as protecting indigenous communities who still suffer from the effects of capitalism today. Here’s are the new names and what they mean to each country.

USA: Columbus Day

Dating as far back as the 17th century, “Columbus Day” – a nation-wide commemoration of the explorer and colonist Christopher Columbus – has been celebrated in the US for hundreds of years. In 1937, the second Monday of October became a federal holiday in the USA. To this day, big street parades and festivities still take place in cities such as New York and Boston in honor of Columbus.

The idea is to celebrate American nationalism, and some will argue that Columbus Day celebrates immigration and exploration. Increasingly, however, there have been disputes over whether this is appropriate and if one culture repressed the other. Some states such as Oregon, Vermont, and South Dakota now dedicate the celebration to the victims of colonialism by changing the name of the holiday to “Indigenous People’s Day” or “Native American Day.” Some have chosen not to celebrate the day at all.

Chile: Day of the Discovery of Two Worlds

Chile’s official name for October 12 used to be Aniversario del Descubrimiento de América (“Anniversary of the Discovery of America”) for much of the 1900s. At the turn of the 21st century, however, Chile renamed the celebration Día del Descubrimiento de Dos Mundos (“Day of the Discovery of Two Worlds”), which suggests that each of the two sides of the ocean realized one another’s existence from their own perspectives. For the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, the country used the slogan Encuentro de Dos Mundos (“The Coming Together of Two Worlds”). Today, Día del Descubrimiento de Dos Mundos is marked by protests, parades, and cultural events that aim to celebrate Chile’s diverse ethnic groups.

Costa Rica: Day of the Encounter of Two Worlds

Most other countries in Latin America knew the holiday as Día de la Raza (“Day of Race”). This name took the limelight off Columbus or “discovery” from a foreign perspective and instead aimed to celebrate the “melting pot” of European and indigenous people that made up Latin America’s multi-cultural society. However, in 1994, Costa Rica changed its official name from Día de la Raza to Día del Encuentro de las Culturas (“Day of the Encounter of Cultures”). Believing that “Dia de la Raza” was still a derogatory and racist label, the new name aimed at promoting and celebrating the ethnic diversity that resulted from the Spanish conquest.

Venezuela and Nicaragua: Day of Indigenous Resistance

Some years after Chile and Costa Rica’s relabelling, Venezuela and Nicaragua decided that it was time they changed the name of the yearly celebration, too. However, President Hugo Chávez took it to the next level. In 2002, he announced that Dia de la Raza in Venezuela would now be called Día de la Resistencia Indígena (“Day of Indigenous Resistance”). For the first time in history, this new name voiced loud and clear that “Dia de la Raza” shouldn’t be about celebrating cultural diversity (created by the oppressor), but should instead honor the bravery of those who fought with their lives to preserve indigenous culture during the Spanish conquest. In 2007, Nicaragua followed suit.

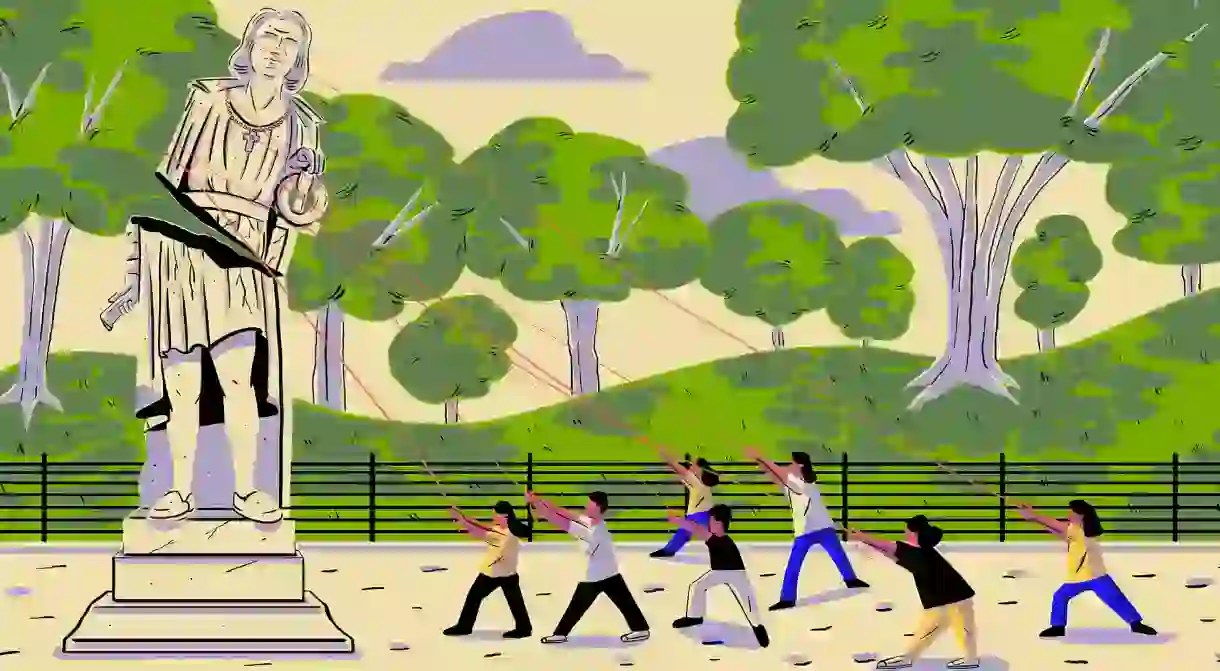

Past events to celebrate Día de la Resistencia Indígena have included huge city marches, the unveiling of new statues of indigenous heroes such as Tiuna (which now replaces the statue of Christopher Columbus in Caracas), and official re-distribution of land to indigenous groups.

Argentina: Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity

Possibly emboldened by Venezuela and Nicaragua’s display of activism, Argentina soon made changes to their celebration as well. Encouraged by former Venezuelan President Chávez, the Argentinian President Cristina Kirchner changed the name from Día de la Raza (which had been established in Argentina in 1916) to Día del Respeto de la Diversidad de Cultura (“Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity”) in 2010.

While not as overt as Venezuela’s choice, Cristina Kirchner’s renaming of Dia de la Raza was followed by a bold gesture: she removed the statue of Christopher Columbus outside the presidential palace in Buenos Aires and replaced it with a 15-meter-high sculpture of female indigenous war hero, Juana Azurduy.

Today, Argentina celebrates Dia del Respeto de la Diversidad de Cultura by giving the day off to all Argentinians and putting on cultural events to encourage awareness and understanding between different ethnicities.

Bolivia: Day of Decolonization

Just a year after Argentina’s decision to change the name marking Columbus’s arrival to the Americas, Bolivia also took an inspired step. On October 12, 2011, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, Evo Morales, announced that Bolivia would now refer to Dia de la Raza as Dia de Descolonizacion (“Day of Decolonization”). But this wasn’t just about appearances; the change in name also marked a considerable change in the celebration itself. Instead of dedicating the day to cultural diversity, Dia de Descolonizacion today is first and foremost about supporting indigenous communities (through redistribution of land, educational events, and governmental funding) who continue to be displaced and underrepresented today.