Read East Timorese Writer Luís Cardoso's Fictional Work "The Skull of Castelao"

The effort by a doctoral student and World Bank employee to locate a sacred cranium results in a madcap caper in the East Timorese selection from our Global Anthology.

P. sat in the chair. With his right hand, he lifted the mug that the sailor had placed on the table, raising it to his lips. He savored the bitter taste of the coffee. He took a deep breath. The scent brought him a sense of inner peace, of a distant land abundant in spices. He’d always dreamed of going on holiday to an island in the South Seas. Maybe Tahiti. Somewhere he could devote himself to the pleasures of painting. But before that, he had a mission to accomplish: to recover Castelao’s skull.

“Where was she?”

A question as urgent as the coffee he’d washed down. P. felt so lonely without her. He had to know her whereabouts. Maybe she could find a way out of the dark alley he was in; a tunnel of light leading to the skull of that Galician nationalist, Castelao. He ordered another cup of coffee. The young lieutenant shook his head and informed P. that he’d just ingested the last batch of the magic brew that had been brought over by Colonel Pedro Santiago, an old colleague of the lieutenant’s father’s and a military career man who’d been posted in Portugal’s easternmost colonies.

“Maybe she’s in Goa!” the lieutenant suggested.

P. once had the opportunity to visit Goa, but because of a hiccup in the flight they’d had to make an emergency landing in Cape Verde. More likely it’d been caused by a divine intervention, brought upon by Germano de Almeida, rather, than an oversight by the Portuguese airline pilot. Gone were the times when people sailed across the Atlantic to go East. P. had never felt particularly drawn to India. Even after joining a sect of the Hare Krishnas, he still preferred the narrow backstreets of Compostela. Kathmandu is on the dark side of desire. On the distant strait of dreams.

India was Portugal’s great love. Little did the Portuguese know then that they were clearing a path for future travelers and penitents who sought to give meaning to their lives. Portuguese poets composed verses exalting the feats of their sailors. Their greatest poet, Camões, who had been blinded in one eye in a war against a Moorish king and his people, was especially driven by a sense of patriotism, which though clouding his reason, didn’t stop him from seeing more clearly than everyone else. Brave men went to sea while cowards stayed on land. There were those who fulfilled the nation’s destiny by making manifest the dream of reaching India, and there were those whose guts were wracked by envy because they had never been. Envy always scares up bad habits, as does gluttony and all the other capital sins.

Then came the pirates, followed by the corsairs, and later came the armadas, who waited in the high seas for the Portuguese ships to begin their journey home so they could loot their load. This saved on energy and effort. What point was there in going to India themselves when others did it for them? The Portuguese seemed not to care. They wanted only to keep their parrots and their dark-skinned Goan girls. The pirates could have the gold. Each went their own way, content. But after years and years of handing over their gold to thieves, they grew tired of it and decided instead to settle in their conquered lands. This marked the emergence of colonels.

P. doesn’t see things this way. To him, the world couldn’t be reduced to the heroic feats of Portuguese sailors. Much less of irascible colonels. Americans had traveled to the moon and returned with a fistful of stones. Not a pirate stepped in their way. Unfortunately for mankind, all they found there were rocks. But what need did they have for rocks when deserts of Arizona are filled with them? Maybe if the Americans had found oil on the moon instead, they would have started fewers wars back on Earth. Even if it meant that star-gazers would have to put up with an unsightly oil pipeline connecting the Moon to Bush’s ranch in Texas.

It was comforting to P. that one of his ancestors had traveled with Vasco da Gama by ship to India, from where he’d returned pleased and perfumed. P. insisted on more coffee.

“It’s all gone!” the lieutenant said. “Just like the Empire.”

P. was not satisfied by his response. He wanted to know more about the coffee’s origins, its provenance, and perhaps also about the mysterious Colonel Pedro Santiago.

“No, his ancestors weren’t Spanish,” the dapper lieutenant of the Portuguese navy said, clearing the air. “He was more like one of those colonels in Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon, that book by the Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado. We Portuguese also took our colonels to the colonies in that epic crossing we now call “The Discoveries.” And what did we get in return? A bunch of telenovelas about the lives of colonels. Column-worthy. Reused. And there were thugs. Militias. But, as I was saying, that colonel was a Maubere…”

“A what bear?”

“Maubere! A lieutenant colonel from Bidau. A town in East Timor. My father, also a colonel, met him while he was posted there. Eventually, he was godfather to Pedro Santiago’s children. All forty of them, each with a different woman. A litter of miniature colonels. His own personal, betrayal-proof army.”

“Let’s not mention betrayal, lieutenant,” the Galician said, in a serious tone. “Keep in mind that Afonso Henriques wasn’t exactly gentle with his Nai.”

“Colonel Pedro Santiago was especially devoted to the Galician town named after Saint James, Santiago de Compostela. A practicing Catholic, the Colonel anointed the Saint as his family’s protector. To my father, the Colonel confided his intentions to embark on an expedition to Santiago de Compostela, his entire army of offspring in tow, to steal Saint James’ mortal remains. Some folk are just fascinated with corpus sancti. But it was just a story, a fancy, a madness of titanic proportions. Even after East Timor was occupied by the Indonesian military, the Colonel never lost faith. He made it his destiny. He claimed East Timor’s occupation by the Moors was a way of forcing the Saint to emerge from his tomb and come to their aid. But the Colonel’s real goal had always been to take the Saint hostage. The apostle would then have to shrug off his mortal remains. But James remained where he was and the Colonel was forced to travel to the Saint himself, arriving in Lisbon shortly after the referendum decreeing East Timor’s independence.

“Why did he want to go to Portugal?” P. asked, his curiosity piqued.

“To bring back his grandfather’s skull, which was thought to have been transported in a shipment of thirty-five skulls from East Timor to the museums of Lisbon and Coimbra in 1882. According to Forbes, in his book, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago (London, 1885): ‘The restoration of peace between two bellicose kingdoms demands the restitution of the captured heads.’”

P. looked at the lieutenant, admiringly. He was in the presence of a worthy interlocutor. He’d always held sagacious sailors in particularly high esteem.

“What’s odd is that no one knows where the skulls are …”

“I gather from what you’re saying that the Colonel returned to East Timor empty-handed,” P. said, scratching his head with his hand.

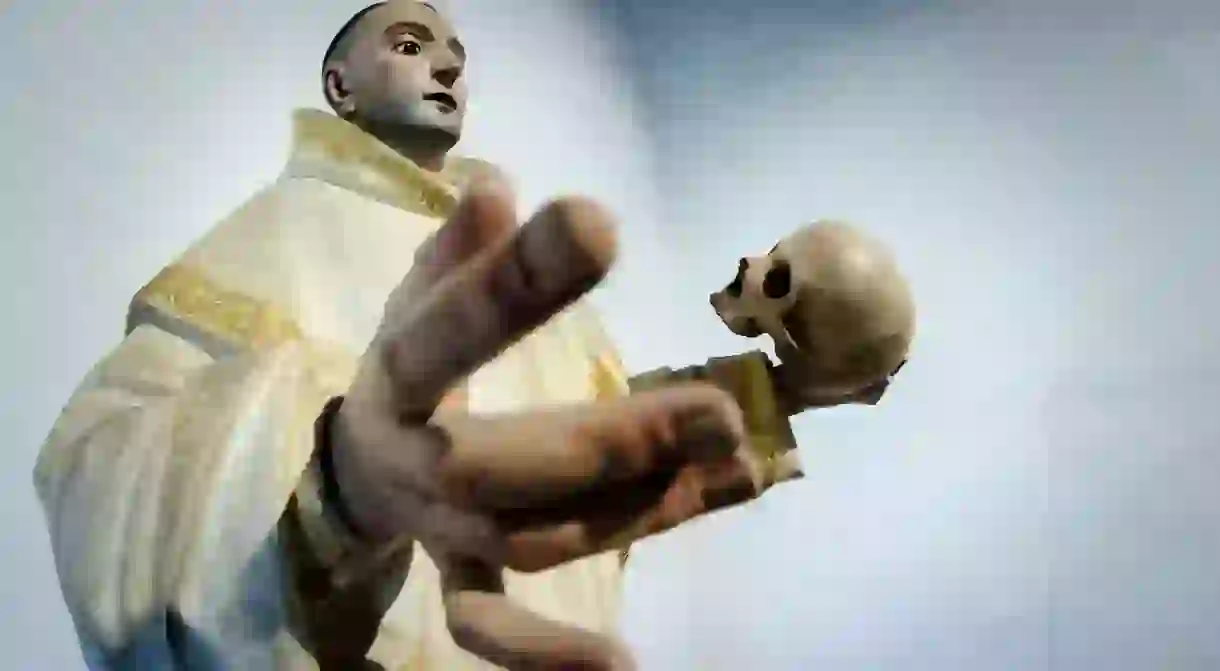

“No, no, that’s not it at all. In fact, when he returned, he was greeted by a parade of delirious fans, all of whom saw the colonel brandishing a skull.”

“The skull?!” P. leapt out of his seat. “And where else did the Colonel travel after he discovered it?” He asked with a curiosity so morbid it made the lieutenant blush.

“He stopped here, in the Azores. He came to see my father and an old friend who’d been a bishop in East Timor. A prelate who has long since joined God. The colonel tried to convince the family to gift him the holy man’s remains, but my father took issue with this and told him that a man should always be buried in the place of his birth. Look, the Colonel even sat in this same chair. He emptied a few bottles of moonshine right here. He was euphoric. Victorious. He held a blue velour bag in his hand. He spoke of his travels to Entroncamento…”

“En-tron-ca-men-to?!”

“A legendary place!”

“Far as I’m aware, En-tron-ca-men-to isn’t registered as a sacred site.”

“But for Colonel Pedro Santiago, it may as well have been. Only later did he decide to visit all those other sites: Fátima, Braga, Compostela…”

“He was in Compostela, too?!” P. opened his eyes in astonishment.

He immediately grabbed the phone and dialed a number.

“I’d like a one-way ticket to En-tron-ca-mento, please!”

“There are no TAP flights available to that destination,” said a voice on the other side of the line. “If you’d like, you can take one of the many buses departing from Santa Apolónia, which take passengers to the remotest places, to lands at the end of the world, to sites of dreams and exile. They have been traveling to Entroncamento for over a hundred years. Some go there to die, like beached whales on deserted shores. That is where they are buried. A cemetery of ancient iron.”

“Pardon the misunderstanding. I meant East Timor. I’d like to go there to help free them of the Moors. My crusading ancestors were also in Jerusalem. The fervent desire to help Catholics is in my blood.”

***

Aboard the TAP plane, which departed from Lisbon, P. was surprised by the presence of someone sitting next to him. He recognized the smell of her perfume, the same scent worn by his American girlfriend. Only later did he realize that the person sitting beside him was the daughter of F., his very respectable doctoral thesis advisor. P. felt disoriented by her presence. He didn’t know her name, had never been informed of her sobriquet. But this didn’t matter to him in the least. She looked so much like Sandra Bullock, that actress from that movie he’d watched online—a movie about spies, he thought—that she’d immediately caught the attention of the other travelers, all of them probably more interested in her tantalizing derriere than whatever intrigue she was involved in. P. felt calmer once she flashed him her ID, which said she was an employee of the World Bank. She smiled maliciously when she informed him that in New York she’d been appointed to counsel a Nobel-winning diplomat on his financial matters and, wanting to put an end once and for all to the constant complaints of their nation’s very important public servant, who demanded coddling equal to his position, she was also tasked with assisting the Minister for Public Incidents, i.e. the Minister for Public Works.

After landing in Comoro International Airport, they shared a car to a small hotel where P. requested a double room. F.’s daughter didn’t seem to mind. But to his despair, he watched as she immediately lay down in bed, fully clothed. He was left with no choice but to do the same. But his eyes were restless. The devil was in him.

On their first day, she went to work. After introducing herself and performing her due diligence, and seeing as many of the ministers were away on duty, she was left with plenty of free time to use as she saw fit. Meanwhile, P. poured his heart and soul into painting portraits of turtles. A species from the dawn of time, they are now on the list of endangered species, in part due to the many natives who use their shells to make artifacts, and serve their eggs in exotic—read erotic—dishes, enjoyed by men with equally endangered passions.

In their free time, they visited cock fights where they hoped to catch sight of the Colonel. P. wasn’t aware that the patterning of a cock’s feathers could sometimes predict the fight’s winning bird, so he lost every bet he made, as well as the photo of Castelao he carried in his wallet, as if it were that of a Galician Pope to whom he felt an almost filial devotion. She hadn’t known the Galicians had even had a Pope. But she smiled at P.’s nerve and at the naivety of the man who beat him in the bet, and who believed a photograph, won in a cock fight, could guarantee him a place in heaven.

And yet there was still no sign of Colonel Pedro Santiago. Trustworthy sources informed them he’d long ago retired from military life and was now a citizen. Having recalled Pedro Santiago’s religious fervor, they started attending mass at the church of Motael. At first this caused the natives some surprise, but their continued attendance convinced even the skeptical sexton, Zacarias, that they were good Catholics. Latin mass, rosaries and purges, confessions and penance, fasting and abstinence: their mission was to infiltrate the world of missionaries. To a worshipper named tía Maria, they introduced themselves as Spanish citizens and members of an important congregation that aimed to restore the Order of the Black Monks of Cluny. The Spanish were respected in that region, even though they’d been lousy neighbors to the Portuguese, or so said their textbooks. But it was from Spain that the Jesuits had traveled to East Timor. The Spanish also boasted such honorable figures as Don Quixote, Ignatius de Loyola, and the Catholic Kings, to mention only the most charismatic. Then there were contemporary celebrities like Raúl Fuentes Cuenca, Julio Iglesias and Jesús Gil. And it was from the mouth of the sexton that they heard of the Colonel’s affinity for the primitive formulation of the Crusades. That two foreigners were mingling with natives did not go unnoticed by the military’s scouts, who were used to reading on the faces of strangers their truest motives. It was clear that these two were after something more than just the salvation of their souls.

It was Zacarias, the sexton, who led them to the Colonel’s house in the Dili neighborhood of Bidau, where the Colonel had always lived with his family. His grandparents had settled in Bidau after leaving the Azorean island of Flores. There, residents spoke a local dialect called Bidau-Portuguese; whenever the colonel used it with the authorities, or to insult his enemies, it was referred to with near reverence as “antipodal Latin.” According to the Colonel, Portuguese swear words had a different bite to them, and nearly always hit the mark.

Pedro Santiago welcomed them into his doorless and roofless house, its walls dotted with geckos that together emitted a sharp, piercing cry. On the floor was a mound of ashes; his house had not been spared the militia’s fury. The colonel sat in a canvas chair, in a white linen suit. In one hand, he held a sword and in the other a sprinkle of snuff.

“Are you Castilian?” he asked straight away, while brandishing his sword at his stupefied visitors.

“Galician, Colonel, Galician!” they answered in unison to avoid any miscommunication.

“Ah, Santiago! My dear Santiago. All I needed was a pair of Galicians, as if there weren’t enough kooks showing up willy-nilly to help free us from the Moors,” he said with a smile. “What do you want from me?”

“We’d like to correct a historical error,” said P. who paid no mind to the regionalism the Colonel had used, as if it exemplified perfectly his self-proclaimed cosmopolitanism, the driving force behind his interest in things across the ocean, in other people’s saints, in strange languages, absurd expressions, lands whose existence was suspect, in railroads that transported him to the mythical train station of Entroncamento, in stone paths that ended in the sea, Finisterre, or wherever it was.

“Colonel, you mistakenly brought back a white man’s skull. A Caucasian man’s. We have a report by experts from Lisbon’s Academy of Sciences concerning this possible, mistaken skull-swap. The skull in the possession of these experts belongs to an Indian man. You know how the Portuguese can be. Whatever’s not Caucasian is Indian. Peccadillos left over from the time of the Discoveries. It’s probably your grandfather’s skull. They say it resembles a colonel’s. It even looks like you.”

“If my memory doesn’t fail me, there were never any pacts between Indians and colonels. One is meant to kill the other,” Pedro Santiago announced. “I hope I won’t be forced to kill a Salesian in my own home.”

“A Caucasian, Colonel, a Caucasian!” his family corrected. Lest someone whisper in the ears of the bishop, a distinguished member of the Salesian congregation, about Colonel Pedro Santiago’s intentions to abolish them from the kingdom of the living.

“It’s all the same,” he shrugged.

“It’s not the same, Colonel,” Zacarias, the sexton, retorted. “You’re comparing apples to oranges. The bishop is Salesian and this man here is Caucasian.”

F.’s daughter added nothing more to her partner’s speech. Nor did she pay much attention to the Colonel’s words. She remained quiet and reserved, like the pious before the altar. She appeared as if mesmerized by the romantic figure before her, a man seemingly lifted from Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. He was like Colonel Aureliano Buendia. In the flesh.

“And who’s to say the experts aren’t mistaken,” Pedro Santiago asked, sarcastically. “Just as they were with the story they spun for over four hundred years, wanting us to believe in the future they’d promised us?”

“You were in Compostela, Colonel!” P. said as he looked around himself, as if searching for an emergency exit.

“As was Almanzor!” the Colonel replied, firmly. He then chuckled loudly, to everyone’s surprise.

“That was many years ago,” P. said. “I’m talking about now.”

“Who is this Castilian man?” the Colonel asked.

“Castelao, Colonel, Castelao. He was a nationalist, just like Xanana!” she said.

“Well, go speak to Xanana then!”

Pedro Santiago got up from his chair. He motioned as if to leave, but she held him by the arm. The Colonel paused. No woman had ever had the audacity to grab him like that. Usually, he reacted violently, but just then he seemed like a boy. He looked at her with lovesick eyes.

“Xanana was never in Compostela!” she said, breaking the spell.

“If you think I stole that Castilian’s skull…”

“Castelao, Colonel, Castelao,” she corrected.

“If I were to steal anyone’s skull…” he paused and threaded the fingers of his right hand through her hair, brushing them along her entire cranium until, suddenly, as if regretting this gesture, he assumed a serene expression and said, “… it would be that of Saint James. But it was someone else I saw in that tomb. Probably that Castilian man…”

“Castelao, Colonel, Castelao!” they both yelled.

They’d grown exasperated by their host’s repeated mistakes.

“My dear guests, do not correct me!” He paused, fixing his eyes on one of his interlocutors and raising his index finger menacingly. “I don’t want any yelling in my house! History pulled quite a trick on you. You should know by now. Someone put a Castilian’s head where Saint James’ should be. That’s the problem. Now go on and find Castelao’s skull. I’m sure it must be somewhere. Once you find it, take it and put it back in its place. On the Saint’s head. Because if you don’t, I’ll give you mine.”

“No, Colonel, please!” they yelled together. “Not another head!”

They quickly said their goodbyes. They wanted to get as far as they could from that megalomaniac. They were even more confused now than when they’d entered his house. Only a lunatic could truly have the patience to fill a book with madcap exploits.

When they stepped out onto the street, P. felt a strange sensation. Like his head was heavier, and he were carrying on his shoulders the spoils of a corpse. He then recalled the Colonel’s words and had the terrible thought that Castelao’s skull was upon his own head. He looked around him, feeling frightened. Afraid of other hunters of memorabilia corporea. Returning to Galicia now would be reckless. He decided to abandon his doctorate and travel to Tahiti to paint the natives. F.’s daughter offered to go with him. In fact she had no plans to leave his side. Professor F. had suspected her feelings for him and he’d tasked her with keeping an eye on P. And that nonsense about her looking like Sandra Bullock? Pure fantasy. A pipe dream cooked up by the scoundrel who wrote the first chapter of this chain-link book, that crazy scientist behind Latim em pó, which masks our faces with its dust, so that we resemble Roman mummies.

Translated from the Portuguese by Julia Sanches. Originally published in and courtesy of the Brazilian literary journal Rascunho as part of a chain-link novel. Luís Cardoso’s memoir TheCrossings was translated by Margaret Jull Costa and published by Granta in 2000. Copyright © 2014 by Luis Cardoso.