New York City’s Hyper-Gentrification With the Author of ‘Vanishing New York’

As New York City’s landscape rapidly gives in to gentrification, author and 25-year resident Jeremiah Moss stands as witness and activist to preserve what he can.

When writer Jeremiah Moss moved to New York City in the early 1990s, hyper-gentrification had already begun. Vanishing New York: How a Great City Lost Its Soul (2017) begins with a description of that experience: “One of the great tragedies of my life was that I had the misfortune to arrive in New York City at the beginning of its end … That experience of having missed out, along with its attendant emotional cocktail of anger, grief, and bitter disappointment, surely helps drive everything I write on New York and its vanishing … But how can I write about the death of New York, the greatest city on Earth, without shaking a fist?”

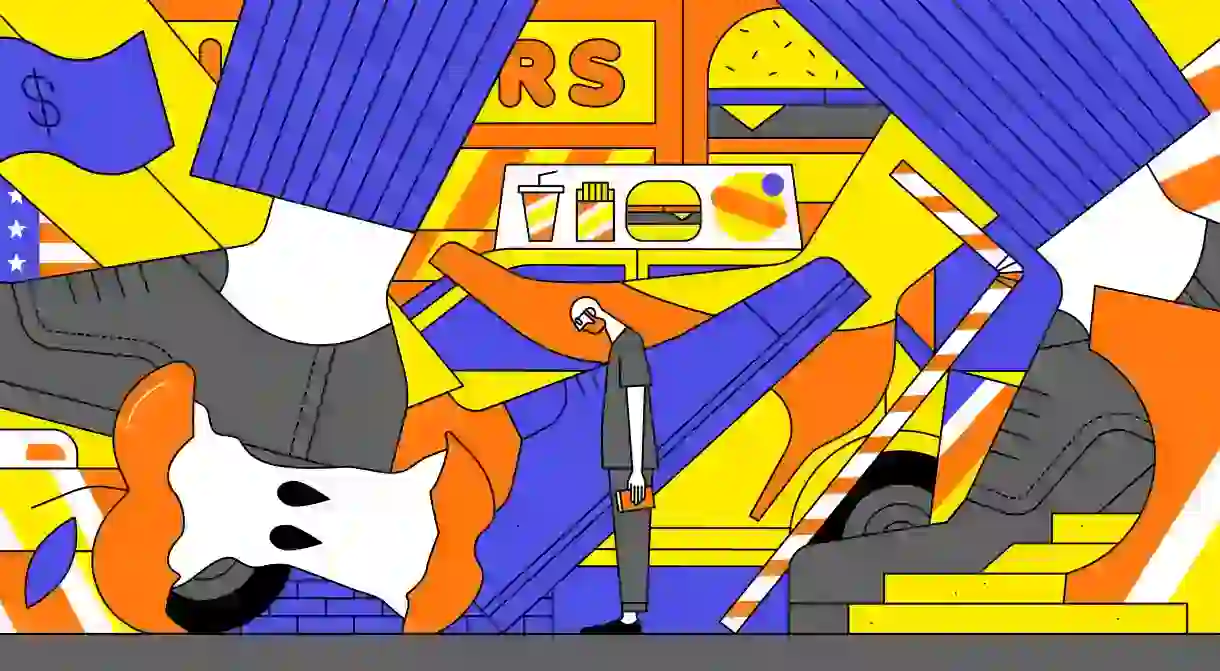

Moss is angry that a vibrant, independent city was commandeered by chain restaurants and drugstores. Moss first began chronicling the changes he saw in his East Village neighborhood in 2007 by writing about the closure of bakeries and bookstores. A decade later, his blog-turned-book, Vanishing New York, preserves the memory of a fading city and attempts to save it from further destruction. Moss breaks down a gentrifying New York through changing city policies, rising rents, displaced people and an influx of the rich to a city that once belonged to all.

“Cities have a long history of being spaces of liberation,” Moss tells Culture Trip. “New York was that in many ways throughout its history. By far not a perfect space, but a better space for immigrants, African Americans fleeing the dangers of the Jim Crow South, LGBTQ people or proto-LGBTQ people coming from all over America. I see the city as being open for the people who need it most.” Or at least, he did.

The warning signs

When Moss first started noticing changes in the East Village, he wasn’t sure if other people were noting the same things. He started documenting the closure of bars and local shops on his blog with images and eulogies. It immediately blew up, and he was profiled by The New York Times just a few months after its inception. Moss had touched a nerve with New Yorkers, who were struggling to put words to the changes they saw. Big Development changed the landscape of the city at faster and faster rates, mom-and-pop shops were torn down to make way for luxury designers, and high-rises replaced rent-stabilized buildings. Moss recorded it all, as well as his own biting critique of hyper-gentrification, in his book a decade later.

“This book is filled with absence,” writes Moss. “The shops that have gone missing, the neighborhoods that have vanished whole, the exiled poets and painters and dancers, the lost men and women who fixed cars and made sawdust and poured the best cappuccino. This book is for them – all of us who came to New York, to the mythical New York … with an ache in our guts, a desperate hunger to become something more, to Be a Part of It, as the song goes, to grab the last gasp of the great city’s big sprawling pounding heart. To you, my fellow desperate and despairing, I say: We was robbed.”

How did we get here?

“[It goes] back to the late 1970s where there was this major shift towards three groups: big business corporation, big developers and tourism,” Moss says. Those efforts worked. Neighborhoods were rezoned with more development-friendly codes. In 1994, a city council vote allowed landlords to move their apartments out of rent regulation after renovation. As a result, both retail and housing rents ballooned, forever changing the landscape of the city.

Starting with his East Village locale, Moss structures his book with chapters on the changing tides of specific neighborhoods, events such as 9/11 and issues like tourism. Gentrification is a complex mix of social, governmental and economic factors, and Moss’s work incorporates heavily researched facts about the nuts and bolts of the effects of each of them. But Moss’s main appeal is an emotional one, like when he examines the High Line Park.

A park transforms the neighborhood

The High Line is a park built on unused elevated train tracks along the west side of Manhattan from just below 14th Street to 34th Street. It was heralded as the city’s answer to the need for more public space. But the park brought a wave of development, completely changing the character of the surrounding Meatpacking District and Chelsea neighborhoods.

Opened in 2009, the High Line quickly topped tourist must-see lists and is visited by about 8 million people annually. “Originally meant for running freight trains, the High Line now runs people, except where they jam together like spawning salmon crammed in a bottleneck,” writes Moss in Vanishing New York. “It is not just tourist crowding and designer curation that makes the High Line so pathogenic. It also helped to overhaul neighborhoods and displace New Yorkers as it grew … In a staggeringly short span of time, the Meatpacking District ended its two-hundred-year history of packing meat, wiping out its infamous sex trade and party scene, became ridiculously trendy, and settled down to a dull but expensive existence as yet another outpost of corporate-suburban America, with the personality to match.”

Moss describes the changes in two major waves. The first wave was defined by high-end designer shops and galleries setting up in the area. But as the neighborhood grew popular with tourists, they weren’t able to afford the luxury brands. The upscale designers were then replaced with chains, molding the city to the needs of the tourist.

Many public spaces are dealing with the issue of overtourism. While writing his book, Moss worked at the main branch of The New York Public Library. “It is impossible to get any work done there because tourists are flooding through that place,” he says. “It is like Times Square. These public institutions that are supposed to serve New Yorkers no longer feel like they belong to us.”

The number of tourists visiting the city each year has nearly doubled from 33 million visitors in 1997 to 62.8 million visitors in 2017. Visitors bring money with them, which can help the city’s economy, but tourism can also have the impact of shifting the city’s priorities to the needs of the tourists – not the people who live there.

Take action

But even tourists have a role to play in the fight against gentrification. Moss advocates for the Small Business Jobs Survival Act, a bill that gives commercial tenants the right to a 10-year lease renewal and equal rights to negotiate a fair lease, making it easier for small businesses to compete against large corporations. “Tourists can write letters to the City Council of New York City,” Moss says. “Write an email saying, ‘Pass this bill because we don’t want to come to New York City and not have any mom-and-pops.’”

Despite his pessimism, Moss still believes in the potential of New York City. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be working so hard to save it.