With a Turbulent Mind, Vincent van Gogh Painted an Unsolved Mystery

When the Hubble Space Telescope captured an image of illuminated star dust in 2004, scientists examined the celestial rendering only to find it oddly familiar. The swirls and billows of stellar turbulence bore uncanny resemblance to The Starry Night (1889), a painted masterpiece forged within the walls of a French insane asylum over a century earlier. The mystery was then as it is now: without possible awareness of this astronomical phenomenon, Vincent van Gogh depicted it with arresting precision. The artist, it seemed, harbored an inexplicable intuition—one that materialized with the tides of his crippling melancholia.

It was six months after his infamous episode of aural mutilation that Vincent van Gogh checked into Saint-Paul de Mausole Asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. His admission was voluntary, and he would create 142 paintings during his time there. Among them was The Starry Night, one of the prolific artist’s most impactful landscapes.

Today, The Starry Night is a jewel in the crown of MoMA’s permanent collection in New York City. Revered as a paradigm of post-impressionism, the painting’s tranquil stillness juxtaposes, perhaps somewhat jarringly, the circumstances of its troubled genesis. In the artist’s months of remission following his notorious act of self-harm, van Gogh seems to have found peaceful moments of harmony not only in, but with nature.

Letters sent to his beloved brother Theo indicate a period of fragile optimism. “This morning I saw the country from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big,” he wrote. Its splendor prompted van Gogh’s timeless portrayal, in which it glows over a sleepy village of rolling hills and verdant cypress trees.

Yet perhaps no element of The Starry Night is as recognizable as the air currents unfurling across the sky. This emotive effect of ethereal movement was achieved through the painter’s employment of luminance, “a measure of the relative brightness between different points,” NPR defines. “The eye is more sensitive to luminance change than to color change, meaning we respond more promptly to changes in brightness than in colors. This is what gives many Impressionist paintings that familiar and emotionally moving twinkle.”

Indeed, the luminosity of van Gogh’s brushstrokes is visually remarkable; but what makes The Starry Night truly extraordinary exists outside the realm of the art historian.

In March 2004, NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team publicized images of a “light echo” captured by the Hubble Space Telescope’s Advanced Camera for Surveys.

The press release explained: “[The] Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh’s famous painting, is renowned for its bold whorls of light sweeping across a raging night sky. Although this image of the heavens came only from the artist’s restless imagination, a new picture from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope bears remarkable similarities to the van Gogh work, complete with never-before-seen spirals of dust swirling across trillions of miles of interstellar space.”

The compelling discovery prompted a team of physicists, led by José Luis Aragón from the Autonomous University of Mexico, to investigate this curious correlation between the “turbulence” van Gogh so artfully depicted, and an impenetrable natural phenomenon known as “fluid turbulence”—a complex theory first articulated by Soviet mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov.

In the 1940s, Kolmogorov proposed a model best described as an “energy cascade—in other words, big eddies transfer their energy to smaller eddies, which do likewise at other scales,” explains Brain Pickings‘s Maria Popova. “Experimental measurements show Kolmogorov was remarkably close to the way turbulent flow works, although a complete description of turbulence remains one of the unsolved problems in physics.” And yet, a mentally-unstable, self-taught painter illustrated the model with baffling precision.

In collaboration with scientists from Spain and England, Aragón measured van Gogh’s inexplicably accurate representation of natural turbulence against the eddies (“probably caused by dust and gas turbulence,”Aragón et al. write in their paper from 2006) captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

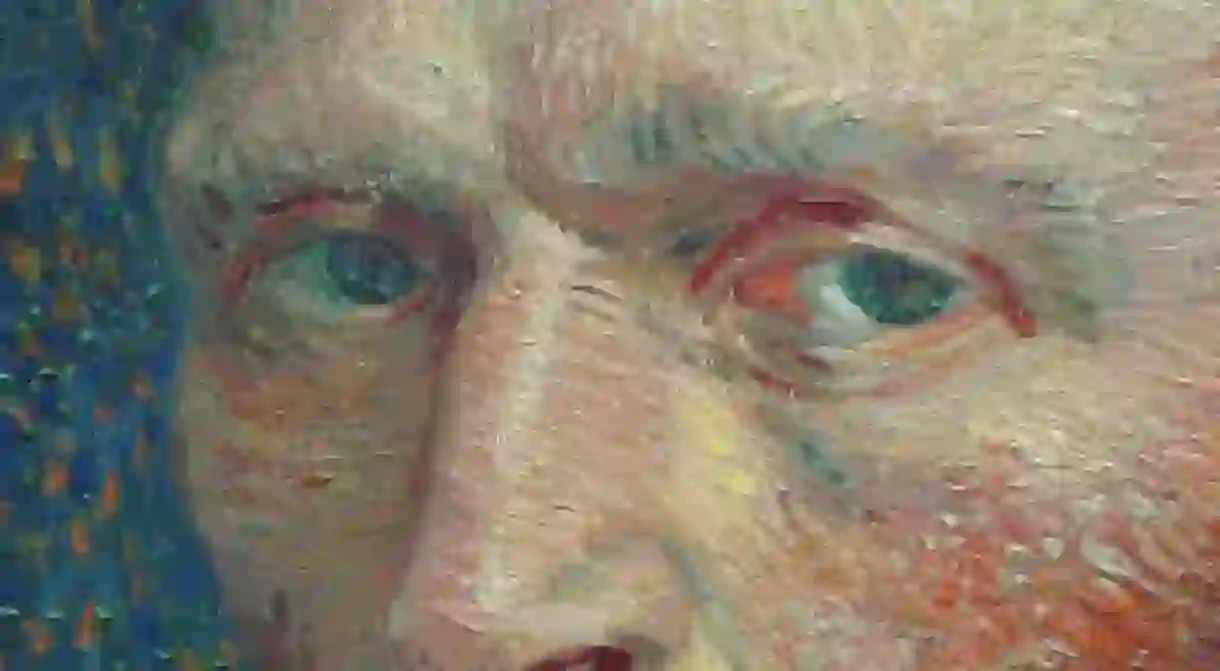

Upon examining digital photographs of The Starry Night, Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe (1889), Wheat-field with Crows (1890), and Road with Cypress and Star (1890)—all of which appear, to the naked eye, as images of turbulence—Aragón and his team successfully identified the cascading pattern referred to as “scaling” that Kolmogorov had used to explain fluid turbulence.

From their research, yet another astonishing pattern emerged. All of the aforementioned paintings tested in the study, except, most ironically, for Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, were created during the ebbs of van Gogh’s tempestuous final months.

“Our results show that [The] Starry Night, and other impassioned van Gogh paintings, painted during periods of prolonged psychotic agitation [transmitted] the [essence] of turbulence with high realism,” wrote Aragón and his associates.

Despite the pleasant imagery yielded in The Starry Night, a letter the artist wrote to fellow painter Émile Bernard described the painting as a “failure.” Notes to Theo van Gogh simply refer to the painting as a “night study,” which, as the artist transcribed, “says nothing.”

Similarly, Wheatfield with Crows is considered to be one of the painter’s greatest works, but it is also credited as van Gogh’s last painting before his death on July 29, 1890. His untimely end is widely accepted as a suicide following extended bouts of depression and anxiety, as well as possible bipolar disorder and epilepsy. Both Wheatfield with Crows and The Starry Night were found to showcase turbulence with mathematical accuracy.

Yet Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, in which the artist acutely addresses the aftermath of his disfigurement, was not a match. While it was created following van Gogh’s gravest depressive episode, he reported painting it in a state of “absolute calm,” likely due to a new prescription of the sedative, potassium bromide.

“By considering the analogy with the Kolmogorov turbulence theory, from our results we can conclude that the turbulence in luminance of the studied van Gogh paintings is like real turbulence,” Aragón explains. “Thus, the distribution of luminance on [these] paintings exhibit the same characteristic features of a turbulent fluid.”

The conclusion reached by Aragón and his collaborators was not only that van Gogh possessed the puzzling intuitive capacity to paint natural turbulence in the first place, but also that this curious ability was unprecedented. “We have examined other apparently turbulent paintings of several artists and find no evidence of Kolmogorov scaling,” the scientists wrote.

“Edvard Munch’s The Scream, for example, looks to be superficially full of van Gogh-like swirls, and was painted by a similarly tumultuous artist, but the luminance probability distribution doesn’t fit Kolmogorov’s theory,” according to the science journal, nature.

As it stands, there is no way to prove that van Gogh’s psychotic breaks endowed the artist with supernatural insight. But as author Natalya St. Clair poetically illustrated in a comprehensive TED-Ed short, “it’s also far too difficult to accurately express the rousing beauty of the fact that in a period of intense suffering, van Gogh was somehow able to perceive and represent one of the most supremely difficult concepts nature has ever brought before mankind, and to unite his unique mind’s eye with the deepest mysteries of movement, fluid, and light.”

Vincent van Gogh died tragically at the age of 37 without any awareness that his work would change the trajectory of his beloved craft. He is universally considered one of the most brilliant artists in history.

“Looking at the stars always makes me dream,” van Gogh once wrote. “Why, I ask myself, shouldn’t the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? Just as we take the train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star.” And so, we should like to think, he did.

The Starry Night can only be seen at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, NY 10019.