Why Judy Chicago’s ‘Dinner Party’ Still Matters, Nearly 40 Years Later

Denounced as a work of kitsch, vilified as pornographic and hailed as a feminist tour de force, Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party still manages to stir up controversy and demand the spotlight – even almost four decades after the final work was unveiled.

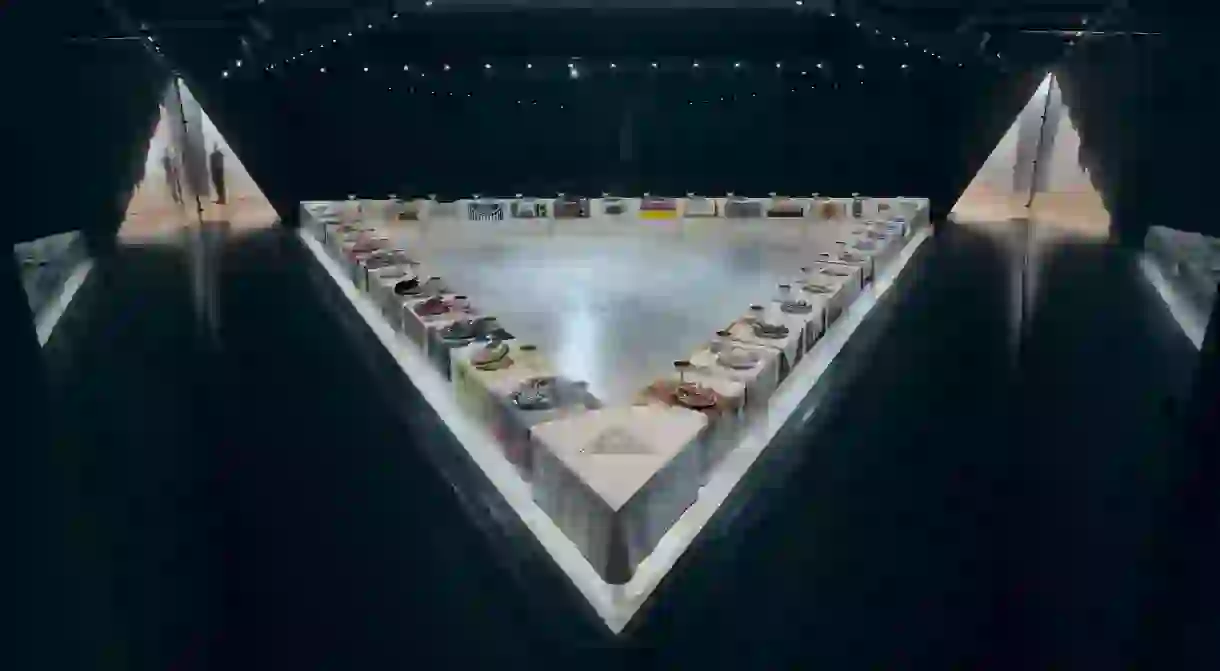

Walking into Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party installation on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Museum feels like a holy experience. Six woven tapestries, scrawled with heraldic language, hang in procession leading to a sacred, solemn encounter with the female form. A triangular banquet table with 39 dinner plates featuring vulvar core imagery for both mythical and historical women are the focal point of this feminist temple. The purpose-built gallery commands a certain hushed reverence; its triangular, yonic forms are echoed on the ceiling, the entrances, the delicate casts of shadow and light. And yet it is the absence of bodies – female bodies – that reverberates throughout the room, commanding the question: Is there a place for women at the table?

“Is The Dinner Party art?” pens critic Hilton Kramer in his scathing 1980 New York Times review published shortly after the exhibition debuted. “I suppose so.” He goes on to call the installation “very bad art” and an “outrageous libel on the female imagination,” even questioning Chicago’s sense of taste. The Dinner Party has continued to provoke visceral reactions from viewers. In 1990, congresspeople called it “pornographic” and “offensive,” ultimately barring its inclusion in the Carnegie Library. But why? What is it about The Dinner Party that makes people so uneasy?

Beginning with the Primordial Goddess’s rippling, billowy vulva, moving to Kali’s purple tendrils and plum center, Mary Wollstonecraft’s wave-like crescent, Artemisia Gentileschi’s layered, velvety place mat and the Snake Goddess’s six-starred center, each ceramic dinner plate is painstakingly unique. “They were being made in the moment where feminist scholars of all fields were really interested in excavating these prehistoric histories that would probably point to a time when men hadn’t ruined the world yet, and women were still worshipped and appreciated for their powers,” says Carmen Hermo, associate curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art and curator of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition Roots of ‘The Dinner Party’. “This idea of the female form – in visual arts, in spirituality – was definitely in the air. So of course The Dinner Party begins with those goddesses.”

And while the presence of the women is definitely felt, there’s another, almost jarring, sensation that accompanies it: No one is actually seated at the table. Although the exhibition is based around the female form, specifically yonic, vulvar imagery, the absence of bodies is palpable: they’re both there and not there. According to Hermo, the audience or observer is needed to complete the work, inviting a sense of temporality and impermanence to the show.

Ranging from curved, egg-like imagery to fiery bursts, the ambitious yet fragile plate designs took nearly 400 workers to complete, and some of the plates were painted in 25 layers, which meant each layer had to be fired in the kiln. “It could break the first time or break the last time,” remarks Hermo. “There were so many experimental attempts.” The entirety of the work took five years to complete.

When it first opened in 1979 at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, the exhibition drew record-breaking crowds. It was meant to go on a multi-venue tour, but after a backlash, most of the other museums canceled. Determined not to let five years’ worth of work go unseen, studio manager Diane Gellen, and many of the nearly 400 people who originally worked on the installation, organized a fundraiser that led to a hugely successful, 14-venue, tri-continental tour. In 2007, the show finally found its permanent home at the Brooklyn Museum’s Sackler Center.

Judy Chicago, who is credited with coining the term “feminist art,” sought to address the overwhelming maleness of art history while also highlighting the erasure of women’s history through the show’s layered symbolism. Each side of the equilateral triangle seats 13 women (39 in total), and the iridescent, illuminated floor contains the names of 999 historical women. “Thirteen is also the number of witches in a coven, so it also had a very female layering to the number,” says Hermo.

For Chicago, the triangle represents equality. “It’s the hope for equality,” says Hermo. “It’s an equilateral triangle and it represents a hopeful future in which, in this case, male and female people are equal. And there is a union of coming together.”

“It’s such an undeniable giant form, around which to build the conceptual structure of the piece … It was largely inspired by seeing these images of the Last Supper, seeing these 13 men at the table … and having this needling question: Who cooked the Last Supper? Who cleaned up? And where are the women?”

By reusing the tools of patriarchal power, particularly through a Judeo-Christian framework, the banquet then becomes a way to honor and celebrate the women, bringing them together in one place. “It’s also the question that we all ask ourselves,” says Hermo. “If you could have lunch with anyone from history, who would it be? You have this idea that these women are together, in conversation, despite their geographical or temporal distances.”

In addition to putting women’s stories (and their bodies) on the proverbial map, The Dinner Party has maintained an ability to initiate new dialogue over the years. The work was a product of Second Wave Feminism, a movement that has since been widely criticized for overlooking racial politics and unique issues facing women of color. The Dinner Party received kickback for its lack of diversity and inclusivity. Immediately following its debut in 1979, Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, was an early critic of The Dinner Party. In Ms. Magazine, Walker pointed out that while all the other dinner plates are “creatively imagined vaginas,” the Sojourner Truth plate shows instead three faces: “It occurred to me that perhaps white women feminists, no less than white women generally, cannot imagine that black women have vaginas.”

In 2017, artist Esther Allen criticized the absence of Latin American women from the banquet table, specifically Frida Kahlo and Gabriela Mistral, highlighting again the lack of diversity at the famed table. Chicago, usually reluctant to respond to critics, penned a letter to The New York Review of Books claiming Allen misunderstood the historical context in which the work was created: “At the time I was working on The Dinner Party, in the mid-1970s, there was little to no knowledge about any of these women. The prevailing point of view was that women had no history. It is important to remember that our research was done before the advent of computers, the Internet, or Google search.”

Hermo, who spent a lot of time with Chicago in New Mexico preparing material for the Roots exhibition, echoes the importance of historical context: “The whole gesture of the piece is the invitation to rewrite history and to question it and break it open … For her, the big absence [of women in art and society] came from gender,” says Hermo. “You see how in 2018, people are thinking beyond the gender binary. They’re taking inspiration from a much more diverse, global history. It ends up being a really important talking point.”

However imperfect, The Dinner Party is a product of its time, an undeniably foundational part of Second Wave Feminism. Its inherent contradictions seem to add to its power, as both a radically political artwork for its day and a poetically fragile, and hauntingly eternal, homage to the female form.

“In the ’70s, people were telling her, ‘No one wants to see this, no one cares,’ and when it actually opened it was super popular,” Hermo says. “Those moments of validation when you realize that art is for more people than the art world – that’s a very beautiful thing.”