Theater: This 'M. Butterfly' Is a Drag

Julie Taymor’s revival of the landmark play at the Cort Theatre misfires as a commentary on gender issues and “Western rape mentality.”

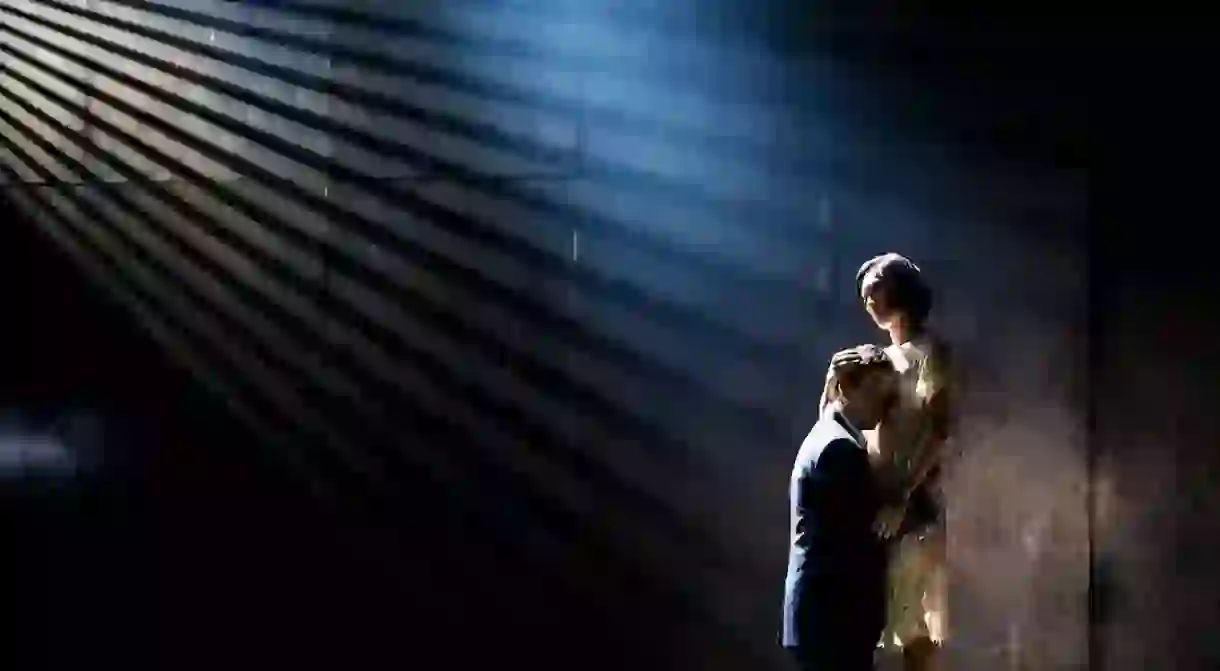

It sounded like a winning combination: Clive Owen directed by Julie Taymor in a provocative American play that was a hit in the 1980s. Although Owen is quite good in the central role, David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly seems far less revelatory now in Taymor’s humdrum production. Instead of soaring, this East-meets-West drama is disappointingly earthbound.

Owen plays Rene Gallimard, a French diplomat stationed in Peking. He tells us his story, beginning with his love of Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly, which he first saw as a 12 year old. At an ambassador’s house in 1964, a Chinese actress, Song Liling (Jin Ha), performs highlights of the opera.

Love blossoms

Afterward Gallimard strikes up a conversation with Song. It leads to a friendship and eventually to an affair. Gallimard believes he’s found “the perfect woman.” His boss at the embassy congratulates him on his romance with a local “lotus blossom.” Song compliments him on being a rare “adventurous imperialist.” Gallimard manages to keep the romance a secret from his respectable wife, Agnes (Enid Graham).

Song eventually tells Gallimard that she was brought up as a boy, to please the Communist authorities. But Song doesn’t tell him the truth, which is that she is actually a man. In the second act, Song reveals how she maintained the illusion of being a woman, even during sex in the dark with Gallimard. Hwang added some of these explicit details for this new version of the play, but they don’t contribute much.

Lacks impact

The plot was inspired by news accounts of a French diplomat, Bernard Boursicot, whose affair with a Chinese man living as a woman became a scandal in the 1980s. From this intriguing story, the playwright makes interesting points about the West’s assumptions about the East—that the former is dominant and the latter submissive, for instance. In the courtroom scene, Song mentions “Western rape mentality.”

Considering the current political standoff with North Korea and the publicity around sexual assault charges brought against Harvey Weinstein and others, M. Butterfly should be more topical and powerful than ever. Instead the play makes less of an impact now than it did in 1988, when it starred John Lithgow and newcomer B.D. Wong.

Taymor, best known for directing elaborate spectacles like The Lion King, would seem to be a perfect match for the play. But her version of M. Butterfly is mostly drab, with only occasional flashes of color provided by costumes and scenery. The most colorful backdrop is of a huge Chinese screen, but it appears in just one scene. The backdrops are made up of smaller panels on wheels. At times there are gaps between them, and occasionally fingers can be seen as stagehands move them into position. It’s a bit cheesy for a Broadway production.

Failed illusion

A more serious problem that grounds this revival is the fact that Jin Ha’s Song never really looks like a woman: the foundation upon which the entire plot line is built. Even the first time we see Song, when she’s in full costume and makeup as Madame Butterfly, she looks rather masculine, and the illusion fails to convince throughout. It’s hard to believe that Gallimard would be so smitten and would continue to believe that Song was a woman for years.

Owen, best known for films like Croupier and Children of Men, made a strong Broadway debut in Harold Pinter’s Old Times two years ago. Here he is once again engaging and believable as a mid-level diplomat who is completely wrong about how the Vietnam War would go, and equally wrong about his “perfect woman.” Sadly, even the dramatic conclusion doesn’t have the impact it should. Once again Taymor’s staging lets down Hwang’s play.

“I am your Butterfly,” Song tells Gallimard just as their unorthodox romance is blossoming. If only we could believe it.

M Butterfly is at the Cort Theatre, 138 West 48th Street. For tickets call 212 239-6200.