Theater: 'A Clockwork Orange' Bulges With Muscles and Ideas

Director Alexandra Spencer-Jones tells us why her stage version of A Clockwork Orange stylizes “ultra-violence” and why the play of Anthony Burgess’ novel is especially relevant today.

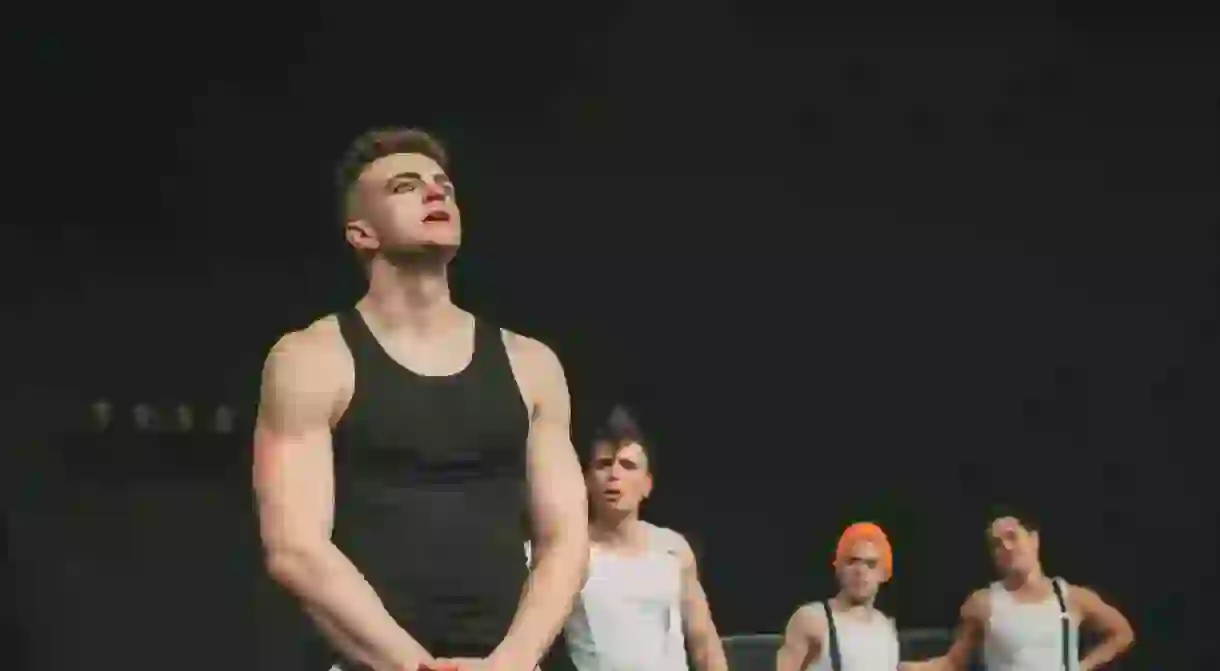

No matter where the audience looks during A Clockwork Orange, male muscles are visible–flexing, tensing, and bulging. The current off-Broadway production of the late Anthony Burgess’ stage adaptation of his dystopian novel about rebellious, disenfranchised youths—and the failed attempts to control them—features an entirely male cast.

Costumed in tight sleeveless shirts and form-fitting pants, the aggressively masculine ensemble stalks the stage, terrorizing passers-by and committing sexual “ultra-violence.”

Secretly read the book

The play, which has traveled the world since 2009 and has arrived at Manhattan’s New World Stages, has been guided from the beginning by Alexandra Spencer-Jones.

Artistic director of South London’s Action to the Word theater company, which is devoted to bringing classics to life, Spencer-Jones first encountered Clockwork’s sociopathic delinquent protagonist Alex DeLarge as a teenager. She was slipped the controversial novel by a renegade English teacher. Jones secretly read the book in bed at night and was enthralled by Alex.

The bare-bones production premiered eight years ago. Since then, Alex and his fellow hooligans, or “droogs,” have journeyed through the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, Asia, and Australia. Rehearsals have been held everywhere, from an empty pub to a crypt under a car park.

The 90-minute play offers an unapologetic look at Alex’s world through his own eyes. Audiences see the droogs wreaking havoc throughout London, and Alex’s arrest, trial, and conviction. They also witness his experience with the Ludovico treatment, a form of aversion therapy applied to render him a non-violent, law-abiding citizen.

Cold, vicious, and merciless

Alex is currently being played by Jonno Davies, who gives a furiously intense performance, while the other eight cast members together play close to forty roles, including those of policemen and doctors. Starkly designed in black and white, with occasional splashes of orange, the production is intentionally cold, vicious, and merciless.

“It was curated for a London art gallery with no budget, no technical rehearsal, nothing else,” Spencer-Jones said in a recent interview. “The only thing we could have was elegance. The play is about the mechanism of the body and the unity of an ensemble. It’s about human function, what it is to be a man, and what it is to suffer [under] the system.”

It took a team to create that aesthetic—a team that includes many women. To help stage scenes of crime and cruelty for this production, Spencer-Jones hired women in the roles of company manager, production manager, assistant stage manager, costume coordinator, and sound designer. The director, who attended military boarding school as a child, said gender is a “fluid thing” for her, adding, “I find female or male company interchangeable myself.”

Because everything looks different in Alex’s eyes than it does to everyone else, the savage attacks in the play are rendered as beautifully choreographed dance scenes set to famous classical compositions.

Taste for the beautiful

Spencer-Jones said she doesn’t want to “sit there and watch ultra-violence” that’s conventionally graphic. In Alex’s mind, he is the star of his own show. “I don’t think he’s got a taste for the horrible. I think he’s got a taste for the extensive and high and, in his own way, for the beautiful.

“It’s my job to empathize with him, which is sometimes a horrible place to be, honestly. I always did that when reading the book, as I think Burgess intended. My job is to maintain my love affair with that character and provide an empathetic view of him to the actors who have taken the role on. It’s also my job to make sure the audience despises and admires him simultaneously.”

It’s Alex’s determination, and his focus, that the director admires, noting the young man’s unwavering discipline. While residing inside Alex’s psyche is a dangerous place to be, Spencer thinks it’s also instructive.

“His quest for greatness pervades his life. He wants to be better,” she said, noting Alex’s self-education in Shakespeare and music, as well as the language—Nasdat—that he uses because the everyday language others speak isn’t good enough for him. “He reaches forward in every way. If there’s a muscle to be had, he will train it into submission.”

Saint Alex

Alex’s perspective makes the play a different proposition to Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film of A Clockwork Orange, Spencer-Jones believes, because receiving it as a horror film or a thriller makes you a helpless witness.

Alex, though, doesn’t think of himself as a criminal, murderer, or sociopath. “I think Alex pictures Alex as a saint,” Spencer-Jones mused. “That’s quite a potent [idea in] our production, as opposed to [what you get] in the film. Alex thinks of himself as the defender of mankind, and in our play never sets out to do anything villainous.The fallout’s nasty, but the ideology is pure to him. “

The purity of the music that’s the main source of rapture in Alex’s life is almost destroyed through the treatment—a devastating experience for the teenager. The painstakingly selected songs were created by artists like David Bowie, Placebo, Gossip, and Muse, who stand for uniqueness, liberation, and the defiance of societal norms.

“Our audience needs to [hear] music the way Alex does: the most powerful driver,” said Spencer-Jones, a composer herself. “Music comprises 44 or 45 percent of the show and drives the action forward. It manipulates emotion, chaos, sadness.”

Burgess was outspoken in his dislike for Kubrick’s film, which took a number of liberties, omitting, for example, Alex’s rejection of his destructive ways.

Timeless and timely

Spencer-Jones—who first saw the film with her father, behind her mother’s back—acknowledges that Kubrick was a great director, “and sometimes it does feel like we’re treading in a giant’s footsteps. More importantly, I consider Burgess a genius, and I made the decision early on to be in love with the film but reject it from the production entirely. The film is a masterpiece. It’s just not the masterpiece I wanted to work with. I wanted to work with the genesis of it.”

A radical difference between Kubrick’s film and Burgess’ play is their settings in time. While the movie is set firmly in the 1970s, Spencer-Jones’ production could take place in the past, the present, or the future. It is not only timeless, she said, it is timely. Stories of disaffected youth and struggles for power endure, and, in the present-day setting, Alex and his droogs could be responding to Brexit or Donald Trump.

“The thing that’s being revealed in the case of Brexit and Trump is there was a huge amount of disaffected people who weren’t being listened to,” Spencer-Jones said. “They went, ‘We needed to make a point. Is that the point that we needed to make?'”

Brexit and Trump “had to happen on some level,” Spencer-Jones added. “I don’t mean the result in both scenarios, but the shakeup that was going to happen.”

‘Listen to us!’

Alex would not like Donald Trump, nor would he follow him on Twitter, according to Spencer-Jones. She said Alex would consider social media an impure way of communicating and, most likely, smash the phones of everyone around him “into oblivion.”

Despite (or maybe because of) its frightening or disturbing elements, A Clockwork Orange has resonated with audiences in every country it has played, Spencer-Jones said. People in those countries also feel they are not being listened to.

The only way that will change is through education, Spencer-Jones said. “We have to educate ourselves now and listen to everyone, whether they’re right or wrong. I think that’s the message in Clockwork. ‘For God’s sake, someone listen to us!’”

A Clockwork Orange concludes with Alex moving forward in life. Is this a happy ending? Reflecting on Alex’s struggles, Spencer-Jones isn’t sure.

In an imperfect world, people can be villains one day and heroes the next, she said, but they can also transcend that. “Alex survives, maybe as a sort of defender of mankind and everyman. Maybe he’s leading us to believe that we can be better. He grows out of [violence]. Whether that’s helpful to us or not, he does. Sometimes I struggle with that, but the play doesn’t. The play says, ‘One does get bored of this stuff and you grow up and change and become better. Tomorrow is a hopeful day.’”

A Clockwork Orange plays through January 6, 2018, at New World Stages—Stage Four at 340 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10019. Visit https://www.aclockworkorangeplay.com/ for tickets and more information.