The Technology Calling the Shots in Tennis

At the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, soccer fans witnessed the most significant introduction of technology in the history of the sport. But in tennis, technology has – quite literally – called the shots for decades.

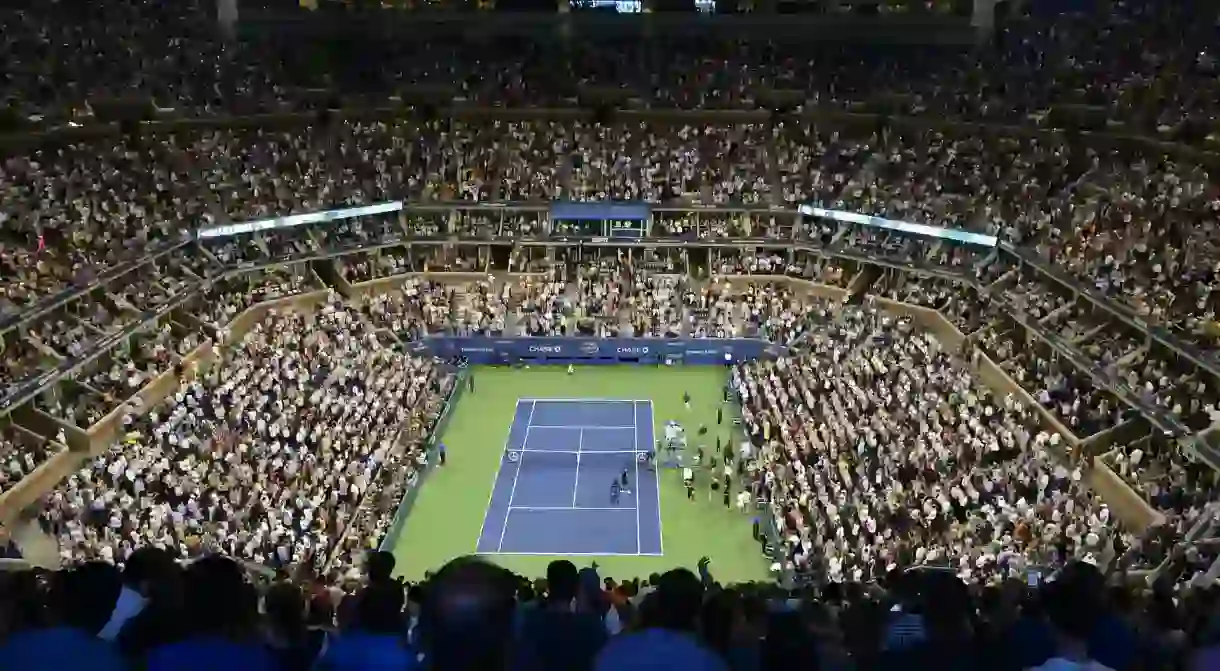

Tennis is no stranger to using technology to adjudicate, practice and promote the sport. The sport has a long history of tech adoption, and the US Open has been at the forefront of that, recently working with IBM’s artificial intelligence Watson both on and off the court.

Perhaps it’s the nature of the sport, but tennis has always been suited to new technology. While the likes of soccer and basketball flow freely, racquet sports have a clear stop-start nature, meaning any interruption can occur without losing the momentum of a match. The sport is also extremely binary in nature. The ball is either in or out, and there is little room for interpretation.

In the 1970s, a system was developed that was able to call when the ball was out. The Electroline-control computer was first publicly demonstrated in 1974, and was used in the Men’s World Championship Tennis finals and the Ladies’ Virginia Slims tour in Los Angeles that year. However, the system – which involved installing plastic pressure sensors under the surface of a carpet court – proved too impractical for a large-scale roll-out.

In 1980, Cyclops was introduced. Rather than being a monster of Greek mythology with a crippling lack of depth perception, it was a computer system which was first used at Wimbledon and was also adopted by the US Open and Australian Open.

The Cyclops system was used to determine if a serve was in or out. The box was placed at the side of the court and projected five or six light beams across it, 10mm above the ground. If the ball broke the beams outside the service line, it would beep loudly, alerting the umpire and players the serve was out.

In 2007, the system was removed from Centre Court and No.1 Court at Wimbledon to make way for the new technology of tennis: Hawk-Eye.

Hawk-Eye was first tested in 2005, by the International Tennis Federation in New York City, and was passed to be used in professional matches. The system, which is also used in cricket and for goal-line technology in soccer, utilizes visual images and data from high-speed video cameras to rapidly process where the ball has gone. It then generates a graphic image of the path the ball took, which can be sent in near real-time to judges, spectators, players or coaching staff.

The system was used in television coverage until 2006, when the US Open became the first tournament to incorporate it into the game itself, allowing each player to challenge the umpire’s call.

And the US Open continues to have a strong tie to technology today. One of the major companies providing that technology is IBM.

“It’s a long-term relationship,” says IBM program manager John Kent. “Over the years it’s continued to evolve in terms of the technology and solutions we provide, but at its core we’re focused on the digital products for the US Open and helping bring the tournament to the world.”

IBM has developed the US Open app, which includes some interesting features for tournament attendees. “Within the app there’s a mobile concierge. Fans will be able to ask natural language questions – know-before-I-go type stuff: what can I bring, where can I park, etc. You’ll get answers back in natural language. This is the third year we’ll have this capability,” explains Kent.

IBM has also developed a cognitive system that can put together a highlights package of a tennis match or day of matches using algorithms. IBM’s Watson AI has been taught to understand the content of a tennis video, such as the sight of a player pumping their fist to celebrate winning a point. It also analyzes audio to identify when the crowd is cheering the loudest, and then uses the metadata to generate graphics for the compiled highlights. These video clips are shared on the US Open social media platforms.

“From a sports perspective in general, I think they’re all starting to embrace the world of data and realizing that there are more opportunities for data,” says Kent. He adds that through collecting data from the line calls, radar and other sources, more information can be sent to the fans to enrich their experience.

Technology doesn’t mix well with some sports – we’re unlikely to see an automated referee in soccer anytime soon – but tennis is at the forefront for a reason. The introduction of AI technology is just the latest in a long history of tech adoption, and it’s exciting for fans and players to see which direction it heads in next.