The Must-See Music Film That Isn't 'La La Land'

No one dances on a freeway or a street or sings in a bright yellow dress in Joe’s Violin. Yet Kahane Cooperman’s inspiring film builds the kinds of musical bridges that make La La Land seem like fluff.

The premise of Joe’s Violin, a 25-minute New York movie that’s vying for the Best Documentary Short Subject Oscar, is disarmingly simple. Joseph Feingold, 91 in the film (now 93), can no longer play his violin. He responds to a WQXR radio station drive that aims to collect thousands of musical instruments for the Mr. Holland’s Opus Foundation, which allocates and delivers them to neighborhood schools.

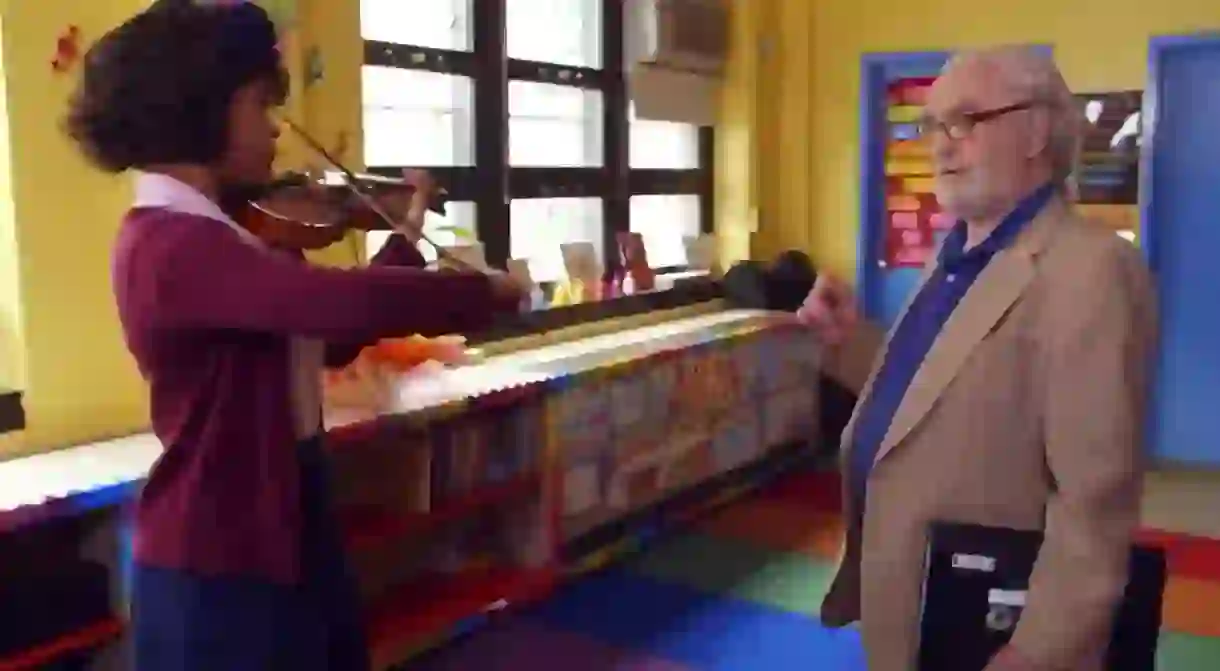

The recipient of Joe’s violin is Brianna Perez, a 12-year-old music student of the Bronx Global Learning Institute for Girls, a school for immigrants. Joe visits Brianna’s school and is moved by her playing of the violin.

Given the current travel ban crisis, a film depicting a meeting between two US immigrants, an elderly Polish Jew and a Dominican-American adolescent, could hardly fail to generate interest. Joe and Brianna are more pertinently linked by their capacity to endure.

Director Kahane Cooperman discreetly uses World War II-era footage and stills, as well as the Feingold family’s black and white photographs, to tell the story of its sundering. Born in 1923, the oldest of three brothers, Joe was encouraged to play the violin by his mother, who enjoyed singing Jewish songs. When the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, Joe left Warsaw for the East with his father, who was sought by the Gestapo. Joe was 17 when the NKVD (Soviet secret service) transported him and his father to separate Siberian labor camps. Joe’s mother and his youngest brother perished at Treblinka. Middle brother Alexander survived Auschwitz.

At the end of the war, Joe, Alex, and their father were reunited at the Zeilsheim Displaced Persons Camp near Frankfurt. Visiting a nearby flea market with Alex in 1947, Joe traded his cigarettes for the violin. He relocated to America, where he became an architect and got married. His wife Regina and brother Alex fleetingly appear on screen.

Brianna’s journey has been less perilous than Joe’s, but she has also suffered loss. Raised solely by her mother, she has wrongly blamed herself for her parents’ split, as the children of broken families often do. A snapshot of her father, who is otherwise unseen in the film, echoes a photo of Joe and Alex’s mother.

Shots taken at WQXR’s office of the donated musical instruments, encased and stacked, recall the filmed images of the heaped suitcases taken from arrivals at the German death camps. Without stating it, Brianna is acutely aware that Joe’s violin might have been a spoil of the Holocaust. “That violin has so many secrets that nobody knows,” she observes.

The tune Brianna plays for Joe is Edvard Grieg’s “Solveig’s Song.” It was chosen because its lyrics have meaning for Joe that only the film should be allowed to disclose. Joe’s response to hearing it again was muted, perhaps because he couldn’t believe his ears. Equally affecting is a closeup of Brianna that appears at the film’s midpoint, immediately after Joe has talked about Grieg’s lyrics and haltingly rendered the tune. As Brianna plucks the notes on the violin with her fingers, she gazes along its neck directly at the camera—and you wonder who previously gave and received such a wondrous look while holding the same instrument.

Joe’s violin can be viewed here. The 2017 Oscar Nominated Short Films, including Joe’s Violin, are currently on release in the US. Find out more about how to watch them OnDemand from February 21st here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6SBZVYyDQOg