The Met Unveils a Landmark Exhibition of Delacroix Drawings

The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents a landmark survey of over 100 works on paper by Eugène Delacroix.

With an oeuvre of monumental paintings such as Liberty Leading the People (1830) and The Barque of Dante (1822), Delacroix (1798-1863) is regarded as a titan of French Romanticism. But those spectacular canvases that memorialize his practice began as humble sketches—premières pensées, or “first thoughts,” as the artist called them—by which Delacroix cultivated the virtuosic compositions present in his best-known masterpieces.

At the Met, Devotion to Drawing charts the evolution of Delacroix’s career, from the early anatomical sketches that trained his eye and hand to his meticulous study of works by the Old Masters. In the final gallery, the artist’s drawings are awash with detail and color, showcasing the culmination of his tireless illustrating.

“Devotion” also refers to Karen B. Cohen’s dedicated acquisition of Delacroix’s lesser-known drawings. An honorary museum trustee who gifted her expansive collection to the Met, Cohen’s extensive assemblage of Delacroix’s works on paper constitute the entirety of this intimate yet significant showcase—the first of its kind in North America for over 50 years. In September 2018, Devotion to Drawing will be met with Delacroix, the first blockbuster retrospective of the artist’s paintings, drawings, prints, and manuscripts in North America, presented in partnership with the Louvre.

Below are nine works on paper in Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix that display the range of the artist’s dynamism.

‘Figure Studies After Rubens’s “Fall of the Damned”’ (verso), c.1820-1822

Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens’ dramatically contorted depictions of the human form were a potent influence on the young Delacroix. Early in his career, Delacroix began copying works by the Baroque painter, including his epic painting The Fall of the Damned (1620). A tangle of bodies is flung down a hellish abyss, serving as an ideal point of study for an artist pursuing mastery of the human body and all its artful contours.

‘Four Studies of Horses’ (recto), 1824-25

In 1823, Delacroix wrote: “I really must settle down seriously to drawing horses. I shall go to some stable or other every morning.” Delacroix subsequently created a number of equine studies throughout his career, considering their form with the same insatiable curiosity as he had humans’.

‘Ecorché: Torso of a Male Cadaver’, c.1828

This graphite and chalk anatomical study exemplifies Delacroix’s initial foray into detailing the very make-up of the human body. While the artist would eventually stray from the rigid boundaries of academic techniques, his practice began at 17 with traditional instruction under Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, and he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts a year later. Upon his death, some 120 undated anatomical sketches were found in Delacroix’s studio.

‘Figure Studies, Related to “Liberty Leading the People”’, 1830

This pen and ink series of figure studies for what would become Delacroix’s magnum opus, Liberty Leading the People, provides paramount insight into the artist’s process. The figures were likely illustrated from memory rather than life, as Delacroix adhered to a three-step method: tracing, freehand copying, and drawing from memory, which was integral to sculpting familiar scenes with his own imagination. The corpse featured in the center of this study indeed figured in the lower right-hand corner of the finished painting.

‘A Wall Decorated in Spanish Tiles’, 1832

At a time when watercolors were far less user-friendly than the transportable palettes that exist today, Delacroix would sketch scenes and patterns on-site with notes marking what colors to add where, and then fill in with paint back at his studio. A Wall Decorated in Spanish Tiles exhibits this process, in which the artist outlined the details of a tiled wall with graphite, and later added color. This drawing was directly inspired by Delacroix’s transformative six-month trip to Spain and North Africa in 1832.

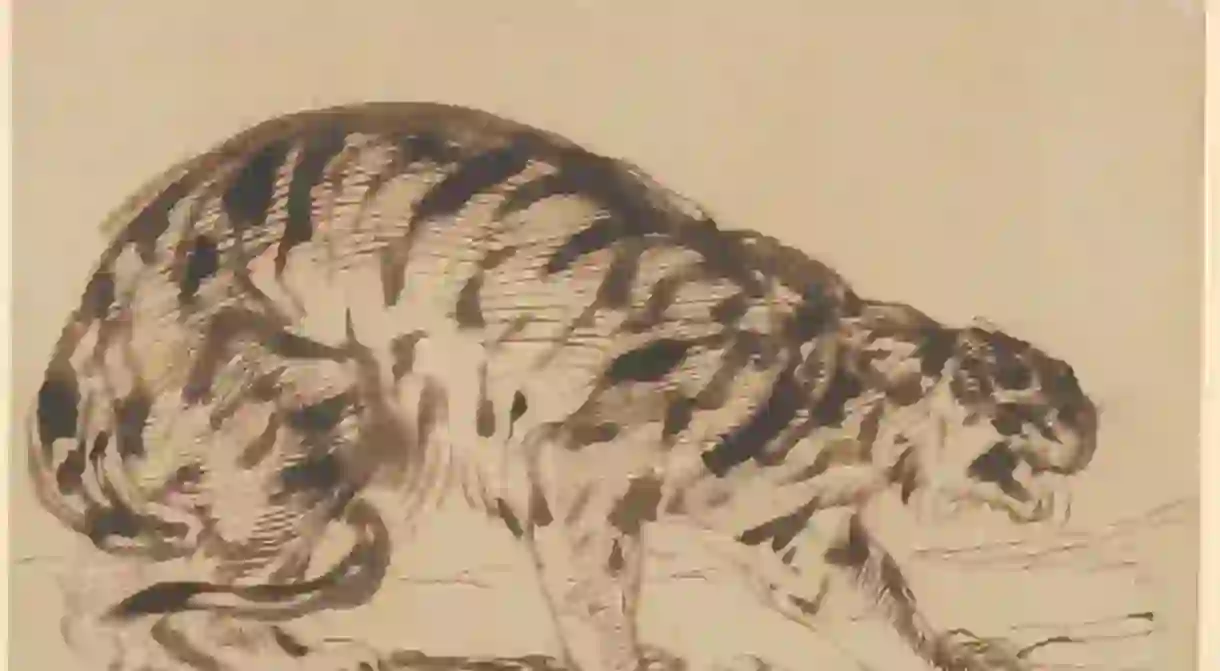

‘A Lion, Full Face, August 30, 1841’, 1841

Delacroix would often visit the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which housed a menagerie of exotic animals including lions and tigers. “How necessary it is to stick one’s head out of doors and try to read from the book of life that has nothing in common with cities and the works of man,” Delacroix wrote. His tutor, Guerin, emphasized the importance of portraying nature, so Delacroix continued to observe flora and fauna.

‘The Agony in the Garden’, 1849

Delacroix’s 1851 oil on canvas painting The Agony in the Garden began as an ink wash and graphite work on paper first sketched between 1823 and 1824. In 1849, Delacroix revisited the subject with another ink wash and graphite work depicting Christ accepting his fate in the Garden of Gethsemane. This monochrome study illustrates Delacroix’s experimentation with tone to convey darkness and doom.

Sunset, c.1850

In the mid-19th century, Delacroix focused his ambitions on capturing and communicating the ethereal qualities of light. Sunset, a pastel image on blue laid paper, communicates a pleasant dusky scene that employs the skilled use of tone and color to convey the depth, dimension, and texture of the sun setting behind clouds.

Page from the ‘Othello’ Sketchbook, 1855

During an 1855 performance of Shakespeare’s Othello at Paris’s Théâtre Impérial Italien, Delacroix sketched several studies of the actors and their costumes. This page from the sketchbook exemplifies Delacroix’s refined artistic process. By this time, Delacroix had mastered the technique of sketching. His subjects were inspired by the world around him, but his work was colored with invention and imagination.

Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugene Delacroix will remain on view through November 12, 2018 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Fifth Avenue location.