Rare Artworks by Hasegawa Tōhaku are Exhibited for the First Time in NYC

This spring, the Japan Society is hosting a two-part exhibition of rare artworks by the influential Japanese painter, Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539-1610).

A historic Japanese tradition of changing one’s name at various milestones made the scholarly investigation into Hasegawa Tōhaku’s oeuvre one of art history’s more fascinating challenges.

Born in the northern coastal town of Nanao, Hasegawa Nobuharu began his career as a decorative painter in local Buddhist temples. Nobuharu hailed from humble means and not much is known about his early life. But his keen eye and legendary confidence would prompt his eventual migration to Kyoto, where in due time he would reinvent himself as Hasegawa Tōhaku: the preeminent painter of Japan’s Momoyama period (1573-1615).

The Japan Society’s two-part exhibition A Giant Leap: The Transformation of Hasegawa Tōhaku is the first comprehensive showcase of Tōhaku’s work in the United States. Tōhaku is a national treasure at home, but due to the delicate nature of the materials he used and the impracticalities associated with transporting his work, the artist’s masterpieces rarely leave Japan.

The unprecedented undertaking of a Tōhaku show was spearheaded by the illustrious 94-year-old Dr. Miyeko Murase—professor emerita at Columbia University and The Met’s former curatorial consultant of Japanese art—in collaboration with Dr. Masatomo Kawai, professor emeritus at Keio University and the director of the Chiba City Museum of Art.

Yukie Kamiya, director of the Japan Society Gallery, explained that this rare showcase aims not only to introduce the artist’s exquisite practice to New York audiences, but to follow his transition from Nobuharu to Tōhaku—a complicated metamorphosis that took some three and a half centuries to identify, and which is still unfolding.

Raised in a common family of cloth-dyers, it’s unknown when or how, exactly, Tōhaku’s penchant for visual art emerged, but he found his niche embellishing the interiors of sacred spaces with Buddhist portraiture and decoration. The artist was both promising and self-assured; Kamiya cited one written account of Tōhaku asking for permission to paint a temple’s sliding panels, and though his request was explicitly denied by the temple master, he snuck in anyway and painted all 32.

Indeed, Tōhaku was notoriously brazen, but his assertive character likely supported his success. The artist moved to the cultural capital of Kyoto around the age of 30. There, he studied both Chinese and Japanese painting techniques under the brief tutelage of Kanō Shōei, whose prestigious Kanō school—renowned for the production of bright, polychromatic screens depicting dramatic landscapes “supplied paintings to Japan’s leading samurai,” according to the Japan Society.

The artist’s timeline is spotty at best, but it was sometime during the late 1580s that he appears to have adopted the name Tōhaku. This coincided with a stylistic transition from religious images to landscape art; from zen painting he moved on to a demonstrated mastery of traditional ink painting called sumi-e, and began creating the spectacular gilded folding screens for which he is known. He subsequently established the Hasegawa school of art, and by 1590, upon the death of his only notable rival from the Kanō school, Tōhaku was established as a leading contemporary painter, with warlords and powerful cultural figures as his patrons.

“Nobody believed that this was all one person’s hand,” Kamiya said of the eclectic works on view at the Japan Society, but in 1964, discerning art historian Tsugiyoshi Doi proposed that Nobuharu and Tōhaku were one in the same. The postulation was bold given the notable stylistic differences in aesthetic and signature; Tōhaku was renowned for his sumptuous gilded screens and ink paintings, while Nobuharu was a rambunctious painter of Buddhist temples. The suggestion of a correlation was long debated in academic circles, but in 2009, the claim found significant credence in the detail of one particular artwork.

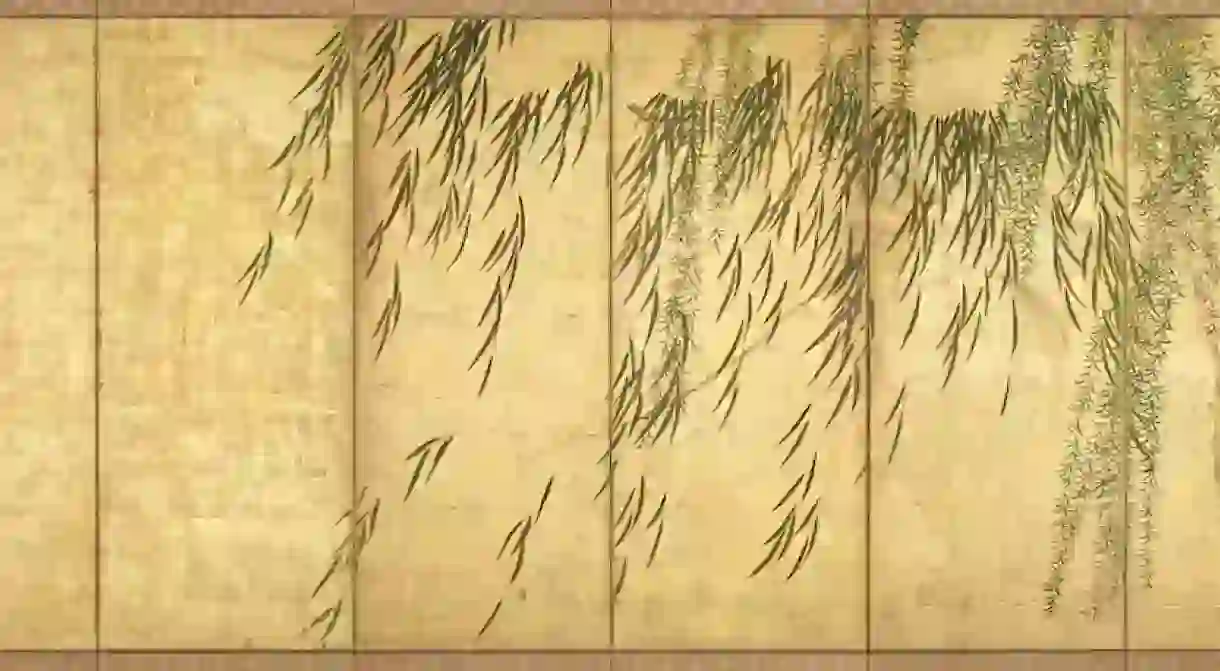

The seemingly separate careers of Nobuharu and Tōhaku were united via Flowers and Birds of Spring and Summer (c. 1582), which is currently attributed to both names. The magnificent, six-panel folding screen serves as the “missing link” between Nobuharu and Tōhaku, as well the centerpiece of A Giant Leap.

From right to left (as Japanese screens are traditionally viewed) this exalted rendering of natural beauty depicts a blossoming crab apple tree in springtime. Flanked by golden banks, a teal stream leads the eye towards summer, which is represented by a verdant pine tree wrapped in wisteria before a cascading waterfall.

“It was the pine tree” Kamiya explains, “its expression and technique” that bridged the perceived gap between Nobuharu and Tōhaku. The tree’s unique details led to the revelation that these two seemingly distinct artists were actually one man who shed his old name and adopted a new aesthetic. There is no signature on Flowers and Birds of Spring and Summer so the attribution is unconfirmed, but the piece has been accepted as the link between Nobuharu and Tōhaku among Japanese scholars and art historians.

The pine tree is present throughout several of Tōhaku’s artworks. A Giant Leap opens in a darkened room with two low-lit folding screens at its center. Neat rows of cushions are placed before the screens to encourage visitors to meditate with the piece. “The installation is set up as the Japanese would have originally appreciated it,” Kamiya informs. “It’s not in a case or on a pedestal; it’s on the floor, so you can sit down on the same level as the painting.”

The screens, both titled Pine Trees, are highly-skilled facsimilies of authentic 16th century sumi-e works by the artist—one of his most treasured and influential masterpieces. Produced for the Tokyo National Museum by the Japanese imaging equipment manufacturer Canon, the reproductions are printed on rice paper and contained by an exact replica of the original frame.

“With blank ink, Tōhaku represented the pine trees, mist, light, wind—everything,” Kamiya notes. “It’s almost abstract.” Though black ink was originally imported from China beginning in the 12th century, ink painting became a Japanese tradition. “One ink represented the whole world,” Kamiya said. “Even invisible elements in nature.”

Tōhaku’s philosophical rendering of the physical environment also employs the power of negative space. Decidedly blank rice paper is used as a powerful tool which allows every viewer to connect with the image and create their own attachment to the piece. Thus Pine Trees introduces visitors to the sparse, monochromatic characteristics of the wildly popular 16th century sumi-e practice that Tōhaku taught himself upon moving to Kyoto. The hitch, of course, being that his aesthetic was inconsistent.

It was also during the 16th century that the Japanese shogunate built splendid castles filled with art to reflect their status and wealth. With his elegant aesthetic and experience in decorative art, Tōhaku became “the favored painter for Sen no Rykyu and the powerful daimyō Toyotomi Hideyoshi and, at the turn of the 17th century, he was summoned to the new capital of Edo by Hideyoshi’s successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu (founder of Tokugawa shogunate), where he remained briefly until his death,” the Japan Society wrote in a statement. Tōhaku lived until the age of 72.

Equal parts stunning and mysterious, A Giant Leap does more than bring Tōhaku’s work to the United States; it serves as a lens through which to imagine a grand and paramount period in Japanese history, when the country opened its borders to Europe; when art was a hot commodity; and when a common man rose up to become one of the nation’s most influential and celebrated—if not completely perplexing—cultural icons.

A Giant Leap: The Transformation of Hasegawa Tōhaku is on view in two rotations. Part I will remain on view until April 8, 2018, and part II will run from April 12 through May 6, 2018 at the Japan Society, 333 East 47th Street, New York, NY 10017.