Never-Before-Seen Photos Perfectly Capture Life in 1930s and '40s NYC

Until now, the photography of Helen Levitt had been long-neglected by the public since her death in 2009 at the age of 95. Levitt was the daughter of Russian immigrants and an artist who documented her native Bensonhurst in Brooklyn and the lively 1940s street life of the Lower East Side and Spanish Harlem. This largely self-taught artist is finally getting her due, thanks to the new collection of her work, One, Two, Three, More from powerHouse Books, featuring an erudite introduction from White Sands author Geoff Dyer.

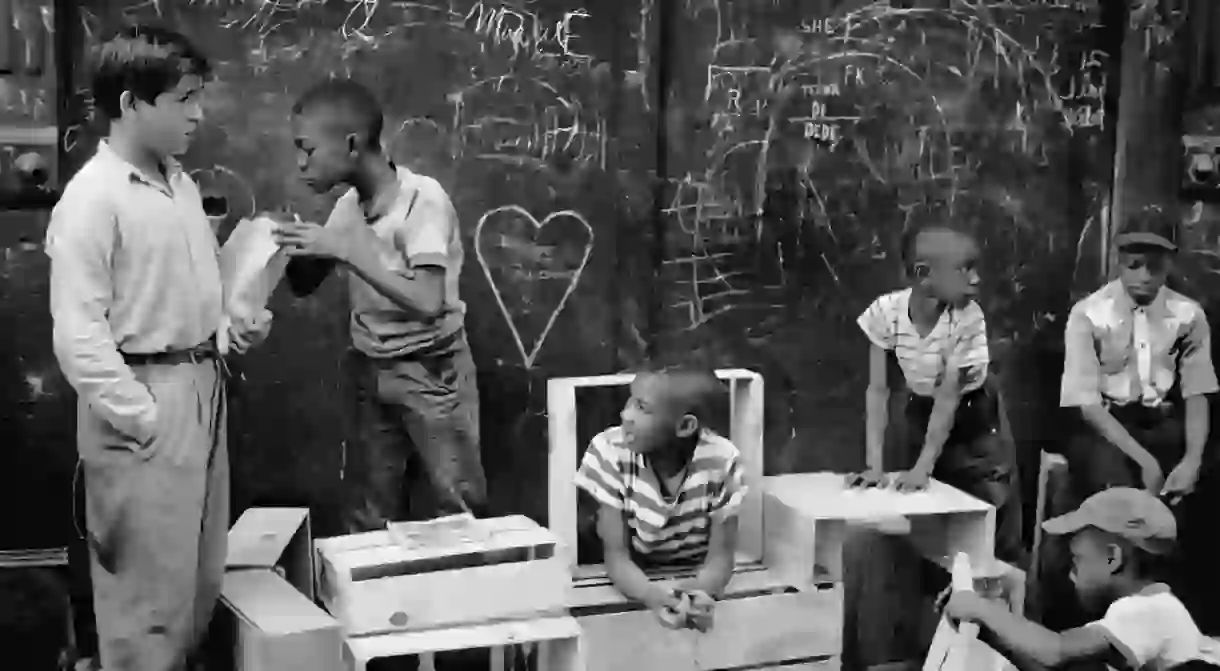

Levitt’s pictures capture the experience of old world families embarking on their new lives in the streets of New York. The book’s enormous sampling of her work—including many previously unpublished photographs—depicts children at play, lovers entwined, old men captured in moments of yearning, and young mothers. Benefitting from the huge influx of immigrants who fled Europe in the late ’30s and early ’40s, as well as the comparative rarity of air conditioning that forced people into the streets of Manhattan and Brooklyn, Levitt began cataloguing her world in 1937, starting with the children’s sidewalk chalk drawings that she first encountered while teaching art classes in the city.

Levitt quickly graduated from the Voigtländer camera to the more professional Leica. A female photographer working in the art world was still fairly unusual in the late ’30s, and Levitt might have grown frustrated if not for the support of her hero Henri Cartier-Bresson, who would become world famous for his portraits of Samuel Beckett, Truman Capote, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. She also enjoyed early support from Walker Evans and James Agee, who had just completed their magnum opus, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. During this period, Levitt also worked as an editor for filmmaker Luis Buñuel.

By 1946, Levitt had come into her own with a grant from MoMA that was followed up with grants from the Guggenheim in 1959 and 1960. She used the funds to compile her 1965 collection, A Way of Seeing. She continued to work well into the 1990s, when sciatica made it difficult for her to lug around her favored camera. By that time, the outdoor culture she had chronicled, filled with children playing and old men smoking, had largely vanished.

Having never married, Levitt’s late-life companion was her cat Blinky, and shortly before her death, she was giving few interviews. Now, at last, her work—in the collections of The Smithsonian, The Met, and MoMA—is available to a new generation of New Yorkers, photographers, and those for whom the life of the street strikes a chord, a reminder of the city’s vibrant immigrant communities and restless population of artists who are dedicated to the preservation of their own personal New York.