First Auction of AI-Generated Art To Take Place in New York

Christie’s in New York City is set to become the first auction house to offer a work of art created by a computer-generated algorithm.

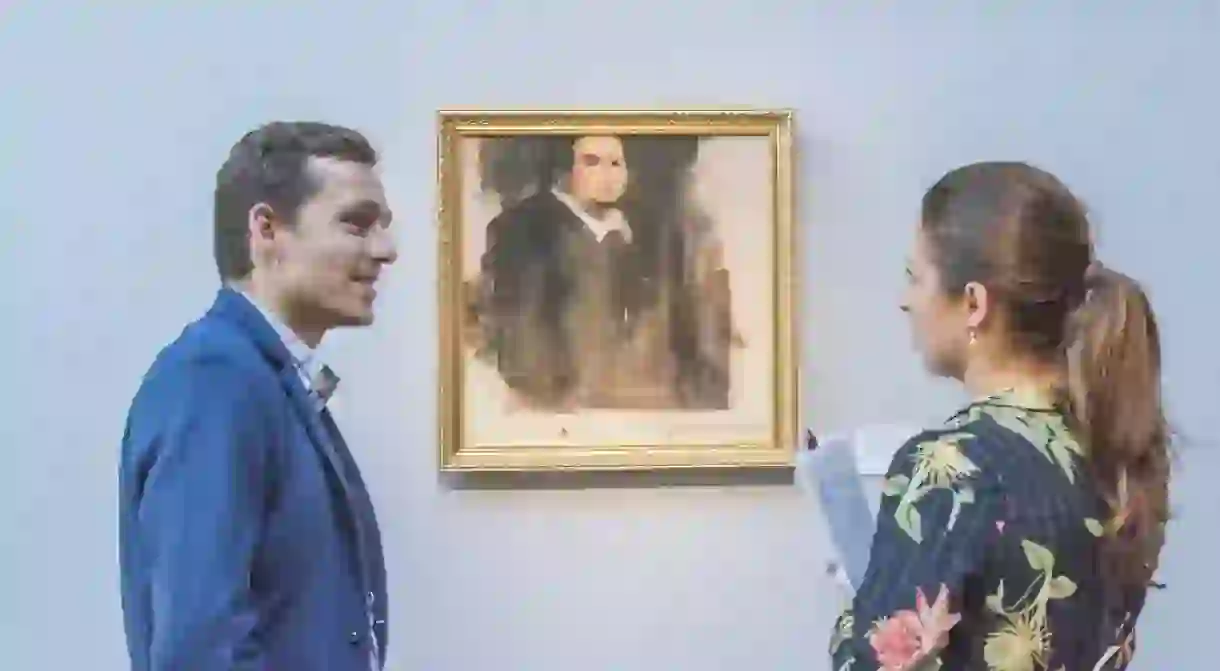

There’s nothing overtly outlandish about Portrait of Edmond Belamy. Sure, the composition is a little unusual – the picture is unfinished and Belamy’s facial features are more smudged than detailed – but his white collar and dark coat suggest a common French cleric and therefore a typical subject of c. 17th-century European portraiture. What is strange, however, is the artwork’s attribution:

min max 𝔼x[log D (x))] + 𝔼z[log(1 − D(G(z)))]

This reveals that Belamy’s image was created not by human hand, but by an algorithm.

Set in a traditional gilded frame, Portrait of Edmond Belamy is estimated to sell for between $7,000 and $10,000 at Christie’s upcoming Prints & Multiples sale in New York City (October 23-25 2018), where it will be the first ever computer-generated artwork presented at auction.

The Paris-based collective Obvious, comprised of Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel and Gauthier Vernier, is behind the rendering. Using a program they call the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), the trio is able to navigate the complex and, as it turns out, surprisingly delicate interface between art and artificial intelligence (AI).

“This new technology allows us to experiment on the notion of creativity for a machine, and the parallel with the role of the artist in the creation process,” said Caselles-Dupré in a statement. “The approach invites the observer to consider and evaluate the similarities and distinctions between the mechanics within the human brain, such as the creative process, and the ones of an algorithm.”

The fictitious Edmond Belamy is the newest addition to Obvious’s series of 11 portraits titled La Famille de Belamy. (The name nods to the GAN inventor Ian Goodfellow, whose surname roughly translates to Belamy in French.) To create the Belamy family, Obvious employed a two-part algorithm consisting of what they called the Generator and the Discriminator. First, the Generator created new images based upon 15,000 portraits fed to it by the Obvious team. The Discriminator then selected the Generator’s most believable output.

The results have yielded eerily human-like portraits in the absence of a human artist or real human sitter. What’s missing, however, is human intent – the desire and emotion that imbues an artwork with meaning.

“For sure, the machine does not want to put emotions into the pictures,” Caselles-Dupré agrees. “And in research terms, the idea of a robot having an open-world experience, and using it to make something new – that is pure science fiction for now.”

The algorithm’s uncanny capacity to create something that is (at least visually) indiscernible from a human creation has prompted Christie’s to spearhead a discussion about AI’s place in art, asking how it will change people’s perceptions and interpretations of art, and whether or not it should be integrated into the industry’s future.

According to Christie’s, if the portrait sells, the proceeds will fund Obvious’s research and finance more extensive training for their algorithm.