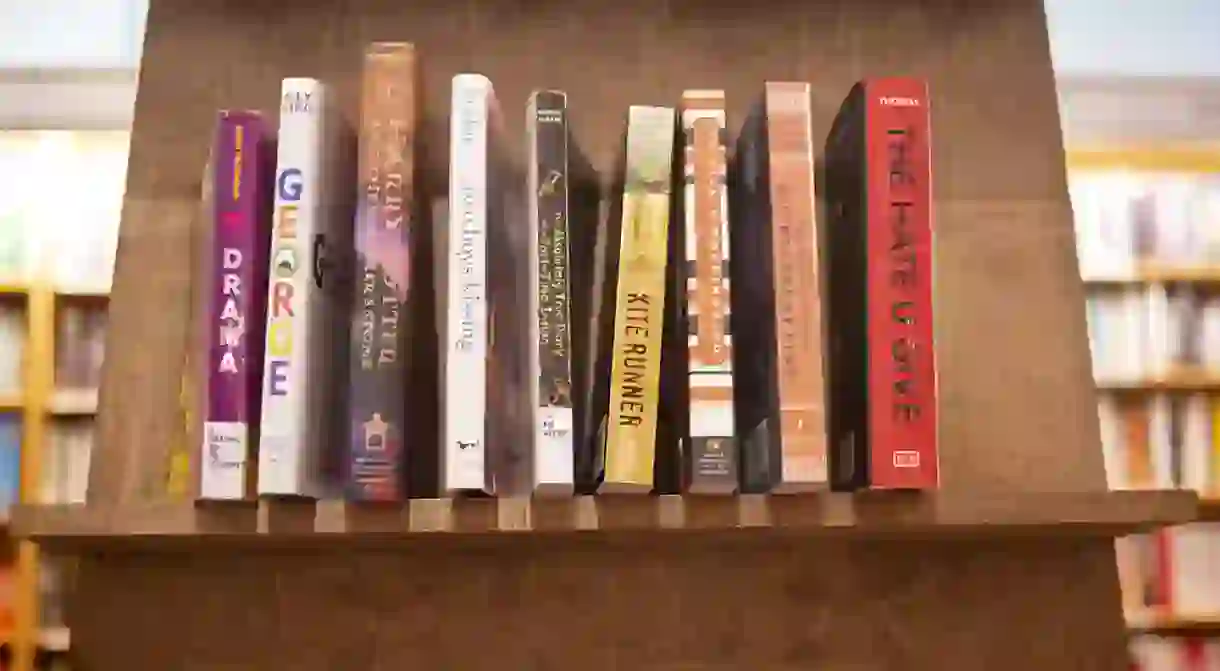

Banned Books Reveal American Anxieties Around the LGBTQ Community

Since 1982, Banned Books Week has highlighted books removed from libraries and schools, and a look at which books were censored over the years reveals deeper truths about the evolving cultural concerns of the United States.

Any time a parent or concerned community member asks that a book be removed from a US library or classroom, librarians and teachers are watching.

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom compiles complaints against books found in either media reports or voluntary report forms to create the annual Banned Books List, first published in 1990. Books that are successfully removed are labeled ‘banned,’ while books that are not removed are referred to as ‘challenged.’ Not all requests for book removal succeed, but Banned Books Week aims to demonstrate how fragile free access to ideas can be.

A look at the most-challenged books over the years can reveal interesting trends regarding the nation’s cultural concerns. The list gives the reasons for any book’s removal, along with its title. The most commonly cited reasons are ‘sexually explicit content,’ ‘offensive language’ and ‘unsuitable for age group.’ In the early 2000s, JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series frequently topped the list with complaints about the promotion of witchcraft, but 2017’s list has no fantasy books at all. Indeed, no book has made the list for objections to occult content since 2013. Instead, sex and LGBTQ identities seemed to be causing the most commotion in 2017.

Author Alex Gino’s middle-grade novel George has topped the most-challenged-books list since it was published in 2015. George tells the story of a young transgender girl who wants to play Charlotte in Charlotte’s Web.

Gino, who uses they/them pronouns, points out the methods of soft censorship that often take place before a book is even published. “Ten years ago, my book wouldn’t have gotten banned because [it] wouldn’t have even gotten published in the first place,” they say. While LGBTQ identities have had minimal representation in books for young readers, LGBTQ young-adult novels have seen a 300 percent increase in publication over the past decade.

Author David Levithan has been writing children’s books with gay characters since 2002, when his book Boy Meets Boy was one of the first in a wave of gay young-adult novels to hit the shelves. But it was not until 2015 that his 18th book, Two Boys Kissing, hit the Banned Books List because of its cover, which featured – you guessed it – two boys kissing. One of the reasons challengers gave was that the book promoted ‘public displays of affection.’

The prominence of LGBTQ books on the Banned Books List points to cultural discomfort with the LGBTQ community, rather than the stated discomfort with sex. While many young-adult novels include sexual acts, it can be revealing to note which ones are flagged. Books with LGBTQ characters and characters of color are often disproportionately represented on the Banned Books List.

While Two Boys Kissing was challenged for PDA, many young-adult heterosexual romance books show kissing on the cover, and they do not appear on the Banned Books List. And given the fact that most books on the list are written for children, the adult content is often minimal. “Frankly, my book isn’t very edgy,” says Gino, “so if you are reading it because someone said it should be banned, you are going to be disappointed.”

If people believe reporting and banning a book means fewer people will read it, Gino’s experience has proved otherwise. In 2015, George was included on the William Allen White Master List, a list of quality and appropriate children’s books, which schools in Wichita, Kansas, use as a guide to buying books for their libraries. The school district made headlines when it refused to buy George, though it did allow the book to be donated to school libraries. “Wichita, at one point, was outranking [sales of my book everywhere] but New York,” the author explains. “For about six months, everyone wanted to know what’s being held back.”

Now Oregon is going through its own censorship struggles with George, and a similar pattern is emerging: “I have more sales in Oregon than anywhere else,” says Gino. “People don’t like to be told what to read.”

Books are often banned because they start difficult conversations. When it comes to George, parents might be uncomfortable speaking to their children about transgender identities. Similarly, instructors today can be uncomfortable contextualizing racial language now considered offensive when they teach historically important books such as Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird. That discomfort is part of the learning process, as books can teach compassion and help fight prejudice. “When you ban a book, there are kids who do not get access to it,” says Gino. “And those are probably kids who actually really need it.”

Gino has a story they like to share to emphasize their hope that literature can continue to push boundaries and make a real difference in readers’ lives: “It’s fifteen years from now,” they say. “It’s a rainy evening. The streetlight is flickering on and off for ambience. There is this really drunk-drunk dude-bro, like PBR drunk. He is just wasted. In the other direction, he sees someone he identifies as a trans woman. Might not be the first trans woman he has seen today; may not be a trans woman. But [his mind goes]: ‘Trans woman, click click click, like Melissa [the protagonist of George],’ and he goes home with a stumble and nothing happens.”