A Rock Movie Tunes In To Tunisia's Revolution

In Leyla Bouzid’s ebullient As I Open My Eyes, the untamed fervor of the Arab Spring is embodied in an impassioned protest singer intent on throwing caution to the winds. On the eve of the 2010-11 Jasmine Revolution that felled Tunisia’s president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, 18-year-old Farah (startling newcomer Baya Medhaffar) fronts a militant neo-prog rock combo and sings recklessly of the people’s discontent.

Equally risky is Farah’s venturing into Tunis’s rough men-only drinking dens. At a party, she also alienates her boyfriend (Montassar Ayari), the band’s normally laid-back lute-player, with her flirtatiousness while unintentionally arousing the undercover government informer in their midst. The consequences of her brashness are harrowing.

The film’s central conflict is between Farah and her anxious mother, Hayet (Ghalia Benali), a former activist who had been forced to relinquish her ideals during Ben Ali’s 23-year dictatorship. The scenes between the two women are charged with the same antagonism and mutual need that characterize relationships between mothers and teenage daughters even in countries immune from revolution.

Bouzid’s writer-director father Nouri was forty when he made his first feature. His daughter was ten years younger than that when her auspicious debut had its premiere at Venice a year ago. A talent to watch, she spoke to The Culture Trip recently from her Parisian home.

You’ve said that the cinema club you belonged to as a student was infiltrated by a government informer. In As I Open My Eyes, it’s a militant Tunisian rock band that’s infiltrated. Did you choose to set the movie in the music milieu because it’s more associated with youth and revolution than movies?

Yes. I wanted the film to have the energy of rock music, but I also wanted to show how the band’s energy is destroyed little by little. You feel that destruction much more if you first hear a lot of songs and then stop hearing them. The audience feels how these musicians have been trapped.

Another thing is that a song’s lyrics can make it fly from one mind to another, which is the sort of thing that makes dictators afraid! It’s harder to show that if the setting is a little cinema club.

Was there a strong music scene that opposed Ben Ali’s oppressive regime in the years before the revolution?

There was a strong underground rap scene and there were reggae singers, but there wasn’t a rock scene. When I was younger, you’d see some rock bands performing at a concert, but then you wouldn’t hear about them again. I was inspired more by the Lebanese and Egyptian rock scenes, though the underground rock band I dreamed up for the film is influenced by traditional Tunisian music.

Tell me about casting Baya Medhaffar as Farah and Ghalia Benali as her mother, Hayet.

Neither is a professional actor. It took me a year of searching in Tunisia to find a girl who could sing and act well enough to play Farah. I met Baya very early on. I told her she had to prepare some songs to sing because she never really had, and she came back and sang some Amy Winehouse. She was seventeen then, not even a high-school graduate. I wasn’t sure about her so we met several times over that year. I made her read the screenplay and we talked a lot. She was really fighting for the role, because she felt very close to Farah, but I took my time because I knew that the spirit of the main actress would dominate the film.

Once I decided on Baya, I started to look for the other actors. Someone told me about Ghalia, who’s a singer and famous in Egypt. She’s a very beautiful, sensual woman – and I wanted the mother, Hayet, to feel that about herself. Ghalia is actually very different from Hayet, though, because in real life she has big hair and tattoos and an extreme mind, but it was fun to transform her into Hayet. She said she played her own mother in the film.

Women were prominent in the Tunisian Revolution. Were you involved personally?

Not directly. I was studying cinema in France and wasn’t there on the day of the revolution, though I pushed my parents to go to the big strike. After Ben Ali had gone, I thought the best way for me to be involved was to make films.

Your depiction of surveillance is double-edged. For example, the band’s manager, Ali [Aymen Omrani], shoots the band in a casual manner, but he’s got a sinister agenda. It adds to the sense that wherever the main characters go, someone is watching them.

I wanted that because that’s how we felt. Before the revolution, every Tunisian had to watch out all the time. We were paranoid about talking politics on the phone or within our families. If we did, it was in low voices. This feeling of fear was quite violent, I think, but it’s over. When you open Facebook or listen to the radio now, everyone is talking politics and being critical. It’s still a big mess, but it’s beautiful that people are learning to express their political ideas while respecting other people’s.

We still have bad police habits, people are still arrested for smoking joints, and violent things happen. It’s no paradise – we have a lot to do – but at least people are talking.

In the bar scenes, which you shot live in Tunis, the men blatantly lust after Farah. It looks as if you captured that deliberately.

Yes, it’s an issue in the film. Women aren’t allowed in bars in Tunisia and if they enter them every man looks at them. I think men are more victims than women because men always have to conform to that macho image. Yes, Farah has some bad meetings with men, but also nice ones.

You mean when she sits with the drunken poet [Fethi Akkari] and charms him with her singing? Is he a real poet – and a real drunk?

He’s an actor, a big man in Tunisan theater. He was acting, but he was also a little drunk [laughs].

There are two romantic triangles in the film, one involving Farah, the other Hayet. In each case, one of the men is an informant. Was that intentional?

It was important to the screenplay. It’s to do with the idea that history is starting again, which is what happens in Tunisia. We had Ben Ali, who was good in the beginning, but then he became a dictator. Also, Hayet sees her younger self in Farah. She doesn’t want her daughter to experience what she did – this feeling of being stuck between the system and a love that is not really possible.

Hayet even starts to resemble her daughter. The mass of her hair looks like Farah’s.

Farah is the main character and we follow her, but then she disappears, and for fifteen minutes we follow the mother, and she almost becomes Farah. At some point they are nearly the same character.

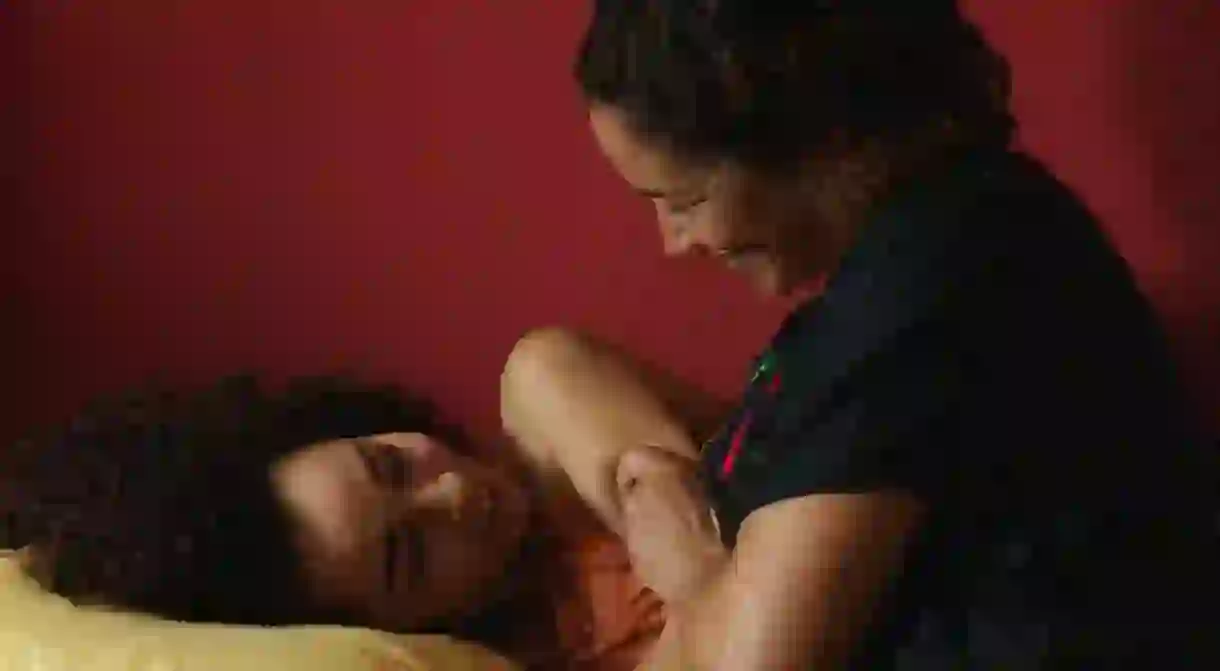

The film has intense moments of maternal and sexual intimacy. Did you choose to work with your cinematographer, Sébastien Goepfert, because he operated the camera on Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Color, which is notoriously intimate?

In fact, Sébastian worked with me at film school [La Fémis, in Paris]. He was the director of photography on my short films before he worked on Blue Is the Warmest Color [laughs]. As I Open My Eyes is his first feature as d.o.p. – it’s the first one, too, for Baya, the producer [Sandra da Fonseca], the composer [Khyam Allami], and me.

How did you make it look so authentic?

Eighty per cent of the actors weren’t professionals, but they were all close to the characters they played and they gave a lot and didn’t feel they were acting – it was real for them. We were lucky because we would film them and then ask them to do the scenes again and again to make them as perfect as possible, and this helped them be emotional. It was important to me that we could believe everything, that the film was organic, and that we could feel the energy I talked about.

The style made me wonder if you’re influenced by Ken Loach or the Dardenne brothers?

I’m influenced by [Turkish-German director] Fatih Akin and [Iranian director] Asghar Farhadi, for example, because of the way they tell intimate stories that have a social impact, but not so much by social realist cinema. I’m more into romance films.

Is Baya pursuing acting?

She hasn’t acted in another film yet and is sad about it, but she’d like to keep on acting. She also wants to be a documentary filmmaker so she’s studying cinema.

Do you know what your next project is?

I can’t say much about it, but I’m writing it now. It’s a love story that will be made in Paris, but it’s very connected to the Arab world.

Finally, Leyla, do you think Farah will hold on to her idealism for a while or that disillusion will sink in?

I don’t want to answer this question because the film doesn’t, but it lets everyone make their own mind up. Half the people who see it think it’s optimistic, half think it’s pessimistic. It’s up to you – you have to decide.

As I Open My Eyes is on release in New York City and screens as part of the SAFAR Film Festival at the ICA, London, Saturday 17 September, 6pm