5 Things You May Not Know About Pioneering Modern Sculptor Brâncuși

At the vanguard of modernist sculpture, Constantin Brâncuși honed an extraordinary practice that transformed the scope of 20th-century art.

Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) rejected the restrictive Western conventions that guided so many of his contemporaries. He borrowed aesthetic and ideological elements from the Surrealist, Dada, Futurist, and Abstract discourses of the European avant-garde, but cultivated a singular style that had never been seen before.

Brâncuși’s reductive, alien forms spearheaded a new brand of abstraction that captivated 20th-century audiences who craved the tides of change. Following his first exhibition at the 1913 Armory Show in New York, Vanity Fair hailed Brâncuși’s work “Disturbing, so disturbing indeed that they completely altered the attitude of a great many New Yorkers towards a whole branch of art.” He went on to gain considerable traction in the City; the renowned photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz hosted Brâncuși’s first solo show at his legendary 291 exhibition space on Fifth Avenue, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum held his first major retrospective in 1955.

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Brâncuși’s far-reaching influence is considered in Manhattan once more. On view through February 18, 2019, Constantin Brâncuși Sculpture exhibits 11 sculptures shown together for the first time, alongside a selection of his lesser-known drawings, photographs, and films.

These five facts about Brâncuși’s career lend context to his revolutionary oeuvre.

Brâncuși briefly trained with Auguste Rodin

Brâncuși received formal training at art schools in Craiova and Bucharest, and in 1904, he moved to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1907, the artist found himself in the employ of modern sculpture’s forefather, Auguste Rodin, but he quit that same year in pursuit of the creative unorthodox. While Rodin established the foundations of modern sculpture with monumental works that were unprecedented for their time, he never truly departed from the realist confines of his craft. Ultimately, Brâncuși figured, “…I was not giving anything by following the conventional mode of sculpture.” He went on to establish his own studio at the Impasse Ronsin in short order.

Brâncuși’s work sparked an important legal battle

Brâncuși forged multiple variations of his 1923 sculpture Bird in Space. One of the artist’s best known motifs, Bird in Space evokes the grace and speed of aviary movement through the streamlined sweep of a featured material – originally cast in marble, with later editions in bronze and plaster. In 1926, Brâncuși shipped a bronze Bird in Space to New York City for an exhibition, but it was intercepted by US customs officials because it “failed to satisfy [the] country’s qualifications for a work of art,” as described by MoMA’s label. The sculpture neither resembled a bird, nor did it appear hand-crafted; however, the court ultimately ruled in Brâncuși’s favor as no two versions of this sculpture are alike. “I never make reproductions,” the artist said. “If I change one dimension an inch all the other proportions have to be changed, and it is the devil’s job to do it.”

Brâncuși’s vision was boundless, but his subjects were few

Brâncuși forged hundreds of sculptures over the course of his career, but despite the infinite reaches of abstract art, he rarely strayed beyond depictions of people and animals. He revisited and reworked his favorite subjects – to include the Hungarian artist Margit Pogany and various avian portrayals – throughout his career; but with few exceptions, he focused on rendering female portraits, children’s heads, and birds.

Brâncuși worked according to a revolutionized technique

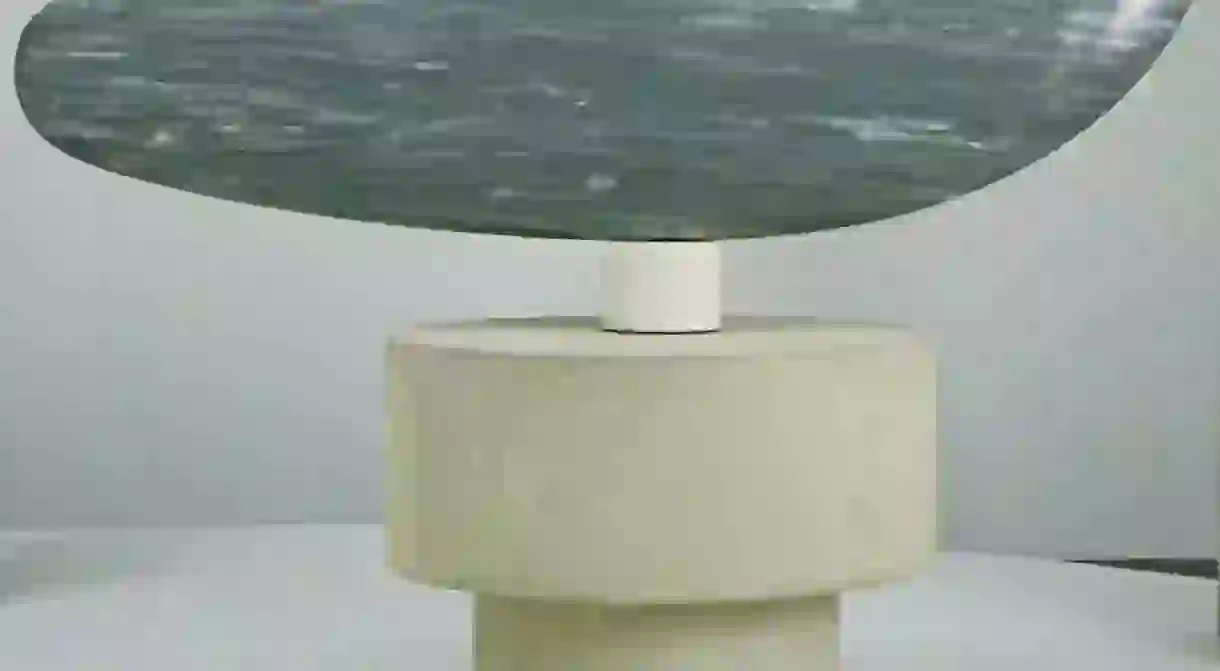

Before he entered the sphere of fine art, Brâncuși honed expertise in wood carving. This skill influenced the technique he adopted later; while Rodin and his forebears cast modeled clay in bronze, Brâncuși carved directly into his materials. He also treated his plinths as part of the artwork, creating them from wood, limestone, and marble, and adjusting their height to emphasize the sculpture’s theme. While his birds were presented on tall pedestals to suggest flight, his portraits and busts are exhibited at eye-level. By integrating his bases into the artwork, he called into question where, precisely, a work of art begins and ends.

Brâncuși was more than a sculptor

Brâncuși established himself as a preeminent figure in modernism, but as MoMA’s survey showcases, he also dabbled in drawing, photography, and film. His drawings were casual depictions of his studio and his work, while his photography served as a direct extension of his abstract aesthetic – often times out of focus with an emphasis on composition. Brâncuși’s films, however, serve among his most experimental work. Guided by his friend and fellow visionary Man Ray, Brâncuși’s films examine material, movement, and light. Not much of Brâncuși’s film work survives, but what remains reveals many of the sources that inspired his sculpture.