10 Must-See Artworks At NYC's Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is home to thousands of historical artworks and artifacts from around the world. New York City is fortunate to have such an institution; there are few places in the world that contain such magnificent works. The Met can be overwhelming in its vast collection, so we give you here are the must-see pieces for your first – or repeat – visit.

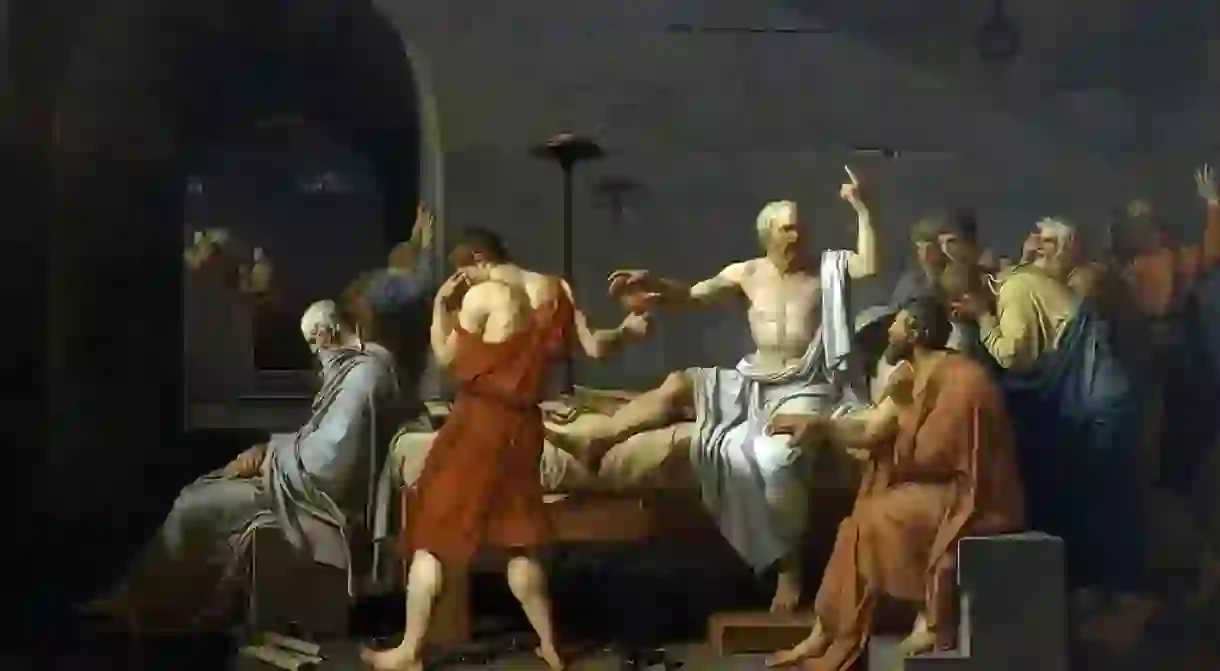

‘The Death of Socrates’

In ancient Athens, Socrates was a profound speaker and teacher – and this was met with great apprehension. As told through Plato’s works, Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth and denying the gods. When given the choice between renouncing his ideas or dying by drinking hemlock, Socrates found great honor in death. In 1787, French artist Jacques Louis David painted The Death of Socrates, a Neoclassical work that shows an unrelenting Socrates reaching for the cup of hemlock as his followers surround him in exasperation and visible sadness. The beauty of Socrates’ integrity is coupled with the artistic accomplishments of the piece, which include amazing perspective and fabric design.

‘The Denial of Saint Peter’

With his life on the line, Peter betrayed Jesus three times. One of the most emotional stories in the Bible, Peter’s denial was an intense subject for the Italian painter Caravaggio. Caravaggio was known for creating art with a sharp contrast between light and dark, and this is central to his work The Denial of Saint Peter, which was completed around 1610. The three fingers pointed at Peter are symbolic of the three times that Peter betrayed Jesus. Regardless of one’s religious beliefs, this work is a stunning display of color that brings out incredible emotion.

‘Young Mother Sewing’

In Mary Cassatt’s painting Young Mother Sewing (1900), the viewer makes eye contact with a young child perched on her mother’s knee as she sews. Cassatt’s work shows the domestic life from her time, but she does so with artistic intricacy. Her broad brushstrokes fill the canvas, and her painting of an everyday scene is something remarkable.

A human-headed winged lion (lamassu)

In the 9th century BC, the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II made huge changes to the area that we now know as Northern Iraq. He was responsible for creating a new capital city, Nimrud, which he designed with great luxury. At the entrance of his palace stood a human-headed winged lion. The sculpture has Assyrian symbols, like a hat that marks divinity and a belt that marks power. The creature, called a ‘lamassu,’ was thought to protect the king and palace from enemies. This lamassu has five legs, which means the creature is standing proudly when looked at from the front, and walking when looked at from the side.

‘Venus Italica’

After the French had taken a statue of Venus from Florence to the Musée Napoleon, King Ludovico I ordered for a new statue to be created in 1804. Antonio Canova’s sculpture, Venus Italica, was probably completed in the 1820s. The sculpture shows this ancient Roman goddess clutching fabric as she peers over her left shoulder. Though she is constructed from marble, she appears incredibly life-like and human.

The Sphinx of Hatshepsut

The ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Hatshepsut lived and reigned in the 15th century BC. At her burial location at Deir el-Bahri, six sphinxes stood guard. Her successor, Thutmose III, ordered that they be destroyed. Ultimately, fragments of the Sphinx of Hatshepsut were collected and reformed to create this enormous masterpiece. The sphinx has a long history in ancient Egypt, and this particular one was crafted with Hatshepsut’s face on its body. Unlike the most notable sphinx that stands in front of the Pyramids of Giza, the Sphinx of Hatshepsut has a nose.

‘Interior of Saint Peter’s, Rome’

Who said that you need to leave New York to see Rome? Giovanni Paolo Panini’s spectacular painting Interior of Saint Peter’s, Rome presents the beautiful extravagance of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Panini created a number of images of the basilica as he traveled to Rome throughout his lifetime. This intricate painting provides viewers with the opportunity to travel across the world, and it shows how the basilica and its visitors were in the 1700s.

‘Dancing Celestial Deity (Devata)’

The Dancing Celestial Deity (Devata) is a sandstone sculpture from the early 12th-century India. This figure stood atop a Hindu temple alongside other female figures to encourage worship for the main deity of the temple. The ornaments and pose make the viewer see rhythm in the stone figure, as it appears to be in motion. Her stance is incredibly enticing and a feat for even the most flexible people.

‘Gertrude Stein’

Gertrude Stein was an American author who was known for having a large following in her Parisian salon. Her salon had famous guests like Henri Matisse, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Pablo Picasso. Picasso painted Gertrude Stein between 1905 and 1906, and it is a testament to his patronage and friendship with the writer. This work appears to be simpler than some of Picasso’s other paintings, and it is a beautiful testament to this important woman in his life.

‘Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form (Shuiyue Guanyin)’

This representation of Avalokiteshvara shows the figure with his right leg bent and his arm draped on his knee. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form (Shuiyue Guanyin) was created in China during the Liao Dynasty in the 11th century. This pose represented the Pure Land, his personal paradise that was later identified to be the island Mount Putuo. The figure’s ornaments are intricate, and the folds in the fabric of his clothing make the figure look realistic.

Want to see more? Make sure you book a stay at one of the best hotels near The Metropolitan Museum of Art through Culture Trip.