You Can Visit Edgar Allan Poe’s Haunting Last Home in the Bronx

A 19th-century farm cottage is one of NYC’s spookiest destinations for locals and visitors with a taste for the macabre.

The Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in the Bronx is everything a Poe fan would want it to be. As befits the last domicile of American literature’s most innovative and influential writer of Gothic horror stories and dread-laden poems, its charm is purely eldritch. The staircase to the attic creaks, the windows admit little light, the rooms are cold, colorless and gloomy. One can imagine Poe’s tortoiseshell cat (Catterina) winding itself around his legs as, consumed with anguish, the author peered into the unheated tiny bedroom where his beloved wife Virginia lay shivering and dying from tuberculosis in the winter of 1846-47.

Surrounded by somber apartment buildings, the white wooden cottage with black shutters sits at the northern end of a narrow park just east of the Grand Concourse at East Kingsbridge Road. It was cheaply built as a house for farm laborers around 1812 and is the last surviving building of old Fordham Village, which was part of Westchester County until it was annexed to New York County in 1874. The village was still rural when the cottage was occupied in the spring of 1846 by Poe, Virginia and her mother, Maria Clemm. Then 37, Poe had already achieved literary fame, but he was so poor he could barely buy food.

Poe originally moved to New York City in February 1837, some eight months after marrying 13-year-old Virginia, who was his cousin. They lived in a wooden shanty on Carmine Street in Greenwich Village. In the summer of 1838, they moved to Philadelphia, where – in January 1842 – Virginia first bled from her mouth, having suffered a hemorrhage, while singing and playing the piano, records Kenneth Silverman in Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (2008). In April 1844, the couple returned to Manhattan; they moved from place to place because Poe found it hard to pay the landlords. In about May 1846, he rented the Fordham cottage from its owner John Valentine (for $100 a year) in the forlorn hope that the country air would slow the progress of Virginia’s chronic illness.

Its recurrences, Poe wrote to a fan, George Eveleth Washington, were more than he could cope with: “Each time I felt all the agonies of her death – and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more dearly & clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity. But I am constitutionally sensitive – nervous in a very unusual degree. I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.” Poe was an alcoholic, and binge-drinking exacerbated his nervous condition.

On February 14, 1846, when the Poes were living at 85 Amity Street (now West 3rd Street) in Manhattan, Virginia had written Poe a Valentine poem eulogizing their love and yearning for seclusion in a home such as the one they found in Fordham a few months later:

Give me a cottage for my home

And a rich old cypress vine

Removed from the world with its sin and care

And the tattling of many tongues

The gossip she referred to was occasioned by a scandal involving Poe and the poets Frances Sargent Osgood and Elizabeth F Ellet.

Jeffrey Meyers tells the story in his Poe biography. The previous month, Mrs Ellet, jealously in love with Poe, had coerced him to return to Mrs Osgood an intimate letter Osgood had written to him. Ellet then sent her brother to retrieve from Poe the love letters she had sent him, not knowing that Poe had already returned them to her. Poe and the brother fought and nearly dueled. The sordid affair “ruined Poe’s reputation as a chivalrous Southern gentleman and his social standing with the New York bluestockings,” writes Meyers. In a letter Poe later wrote to another poet admirer, Sarah Helen Whitman, he claimed Virginia had said “Mrs E. has been my murderer” on her deathbed.

Virginia died in the Fordham cottage’s downstairs bedroom at the age of 24 on January 30, 1847, propelling Poe into crushing melancholy. It is said he spent wintry nights crying over her grave in the Valentine family vault. Looked after by Maria, he stayed on at the cottage, continuing to write into the early hours when not deranged or drunk. Virginia’s death inspired his poems ‘Ulalume: A Ballad’ and ‘Annabel Lee’ (his last one), both written at Fordham and suffused with morbid longing. ‘The Bells’ and ‘Eldorado’ were also written in the cottage, as were the stories ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ and ‘Hop-Frog,’ the long prose poem ‘Eureka’ and other pieces. Hailing from this period, too, is ‘Landor’s Cottage,’ Poe’s idealized portrait of the cottage and the surrounding vegetation (which included a towering tulip tree); it was the last of his works to be published while he was alive. Along with all of Poe’s Fordham poems, this peculiar story is reprinted in full in a $15 booklet available at the cottage’s modest gift counter.

In his last years, Meyer writes, Poe lectured, tried to raise funds for his never-realized literary magazine The Stylus, roved up and down the East Coast and pursued a quartet of female admirers, including Mrs Whitman, who – because of Poe’s inability to stop drinking – called off their engagement two days before they were to be married on December 25, 1848. Poe died in mysterious circumstances in Baltimore at the age of 40 on October 7, 1849. He was buried at Baltimore’s Westminster Hall and Burying Ground on October 8. Maria learned about his death only the following day. Shortly afterward, she left the Fordham cottage. She herself died in Baltimore at the age of 80 in 1871, having spent her last 20 years as a nomadic dependent on the financial help of friends and well-wishers. (Henry Longfellow and Charles Dickens sent small amounts of money to her.) Maria was buried in the same graveyard as Poe – where, in 1885, Virginia’s bones were also interred.

In disrepair by the 1890s, the Fordham cottage was saved by the New York Shakespeare Society, which lobbied the New York City Legislature to have it moved about 450 feet north of its original location on the east side of Kingsbridge Road near 192nd Street. It was relocated to the site of a former orchard that had been consecrated Poe Park in 1902. The drawn-out 21st century renovation of the park, due for completion in 2019, has seen the building of a visitor center and gallery space, which opened in 2011. The gray Modernist building was designed by the architect Toshiko Mori to suggest the shape of a raven, thus honoring Poe’s most famous poem.

The vertical picture window in the northern end of the visitor center looks out on Poe’s humble cottage, which is open to the public. The cherry and lilac trees that Poe once looked out on from the veranda are long gone. The ground floor consists of a kitchen, a parlor and a tiny bedroom that was probably Maria’s until Virginia was no longer strong enough to mount the stairs. In the attic, there is a small room that was Poe’s study and a larger room that was his and Virginia’s bedroom. It now contains a TV that shows a 20-minute documentary, featuring an actor playing Poe, about the writer’s Fordham experiences, including his frequent nocturnal wanderings.

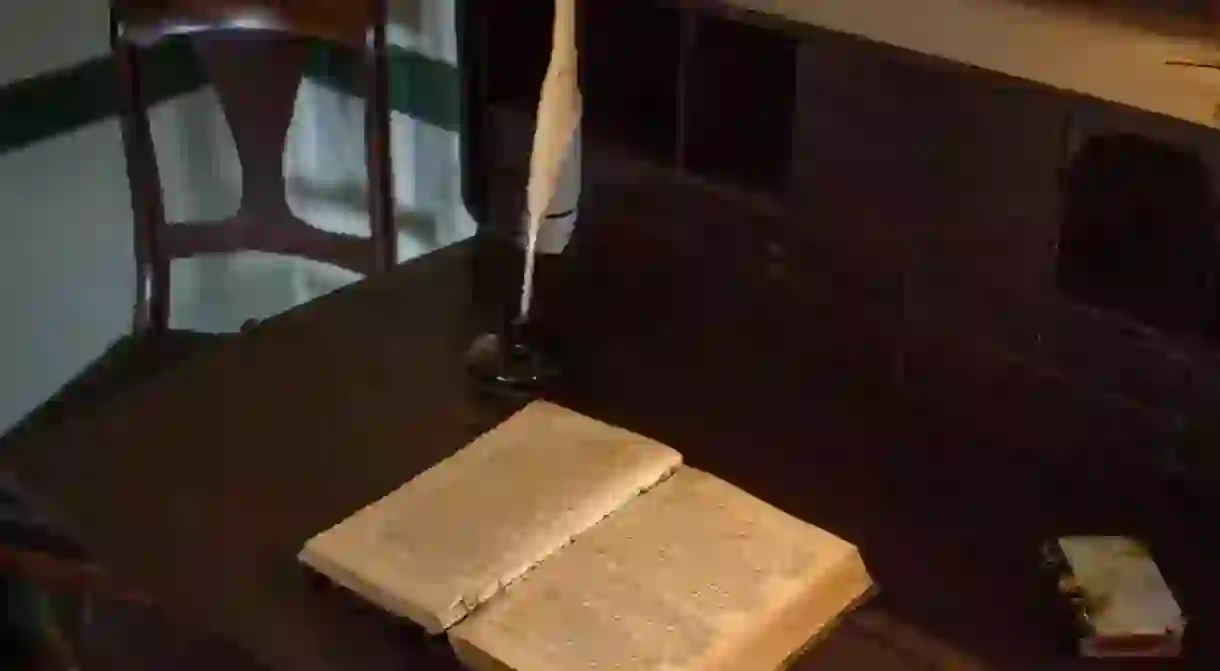

The cottage is sparsely furnished, exactly as it was in Poe’s day, when, however, it exuded greater gentility thanks to Maria Clemm’s housekeeping. It contains two items believed to have belonged to the Poes: a wicker rocking chair and – lending to the sepulchral aura – the slender bed in which Virginia died. The gilt-edged oblong mirror is a reproduction of one that belonged to Virginia. There are also hearths, an ancient free-standing kitchen stove, items of donated period furniture and a 1909 centenary bronze bust of Poe.

Be sure to bring your cell phone when you visit the cottage because the call-in audio tour (included with the $5 admission fee) discloses nuggets of information about Poe, the cottage and its environs listed according to numbers pasted beside various prints and photographs. For example, the sound bite accompanying a copy of the famous Ultima Thule daguerreotype of the haggard Poe explains that he posed for it in a studio in Providence, Rhode Island, on November 5, 1848, four days after he took an overdose of laudanum (an opiate) in a possible suicide attempt. As the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore reports on its website, it was Mrs Whitman who gave the portrait its name, likening its creation – “after a wild distracted night” – to the nightmarish life journey of the narrator in Poe’s 1844 poem ‘Dream-Land’:

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule –

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE – Out of TIME

The Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, 2640 Grand Concourse at East Kingsbridge Road, The Bronx, NY 10458. Open to the public Thursday and Friday, 10am-3pm; Saturday, 10am-4pm; Sunday, 1pm-5pm. Admission $5 adults, $3 seniors, students and children. Take the D or 4 train to the Kingsbridge Road Station. Audio tour telephone number: +17189712156.